Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon with improved strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels, which are resistant to corrosion and oxidation, typically need an additional 11% chromium. Because of its high tensile strength and low cost, steel is used in buildings, infrastructure, tools, ships, trains, cars, bicycles, machines, electrical appliances, furniture, and weapons.

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with air being blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten.

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silica and other constituents of dross, which makes it brittle and not useful directly as a material except for limited applications.

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content in contrast to that of cast iron. It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions, which give it a wood-like "grain" that is visible when it is etched, rusted, or bent to failure. Wrought iron is tough, malleable, ductile, corrosion resistant, and easily forge welded, but is more difficult to weld electrically.

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon are removed from the sourced iron, and alloying elements such as manganese, nickel, chromium, carbon and vanadium are added to produce different grades of steel.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

Industrial processes are procedures involving chemical, physical, electrical, or mechanical steps to aid in the manufacturing of an item or items, usually carried out on a very large scale. Industrial processes are the key components of heavy industry.

Basic oxygen steelmaking, also known as Linz-Donawitz steelmaking or the oxygen converter process, is a method of primary steelmaking in which carbon-rich molten pig iron is made into steel. Blowing oxygen through molten pig iron lowers the carbon content of the alloy and changes it into low-carbon steel. The process is known as basic because fluxes of burnt lime or dolomite, which are chemical bases, are added to promote the removal of impurities and protect the lining of the converter.

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-finished casting products are made from molten pig iron or from scrap.

An electric arc furnace (EAF) is a furnace that heats material by means of an electric arc.

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgical or process furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term reverberation is used here in a generic sense of rebounding or reflecting, not in the acoustic sense of echoing.

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ironworks is ironworks.

Puddling is the process of converting pig iron to bar (wrought) iron in a coal fired reverberatory furnace. It was developed in England during the 1780s. The molten pig iron was stirred in a reverberatory furnace, in an oxidizing environment to burn the carbon, resulting in wrought iron. It was one of the most important processes for making the first appreciable volumes of valuable and useful bar iron without the use of charcoal. Eventually, the furnace would be used to make small quantities of specialty steels.

Direct reduced iron (DRI), also called sponge iron, is produced from the direct reduction of iron ore into iron by a reducing gas which either contains elemental carbon or hydrogen. When hydrogen is used as the reducing gas there are no greenhouse gases produced. Many ores are suitable for direct reduction.

Electrometallurgy is a method in metallurgy that uses electrical energy to produce metals by electrolysis. It is usually the last stage in metal production and is therefore preceded by pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical operations. The electrolysis can be done on a molten metal oxide which is used for example to produce aluminium from aluminium oxide via the Hall-Hérault process. Electrolysis can be used as a final refining stage in pyrometallurgical metal production (electrorefining) and it is also used for reduction of a metal from an aqueous metal salt solution produced by hydrometallurgy (electrowinning).

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

Pierre-Émile Martin was a French industrial engineer. He applied the principle of recovery of the hot gas in an open hearth furnace, a process invented by Carl Wilhelm Siemens.

The Gilchrist–Thomas process or Thomas process is a historical process for refining pig iron, derived from the Bessemer converter. It is named after its inventors who patented it in 1877: Percy Carlyle Gilchrist and his cousin Sidney Gilchrist Thomas. By allowing the exploitation of phosphorous iron ore, the most abundant, this process allowed the rapid expansion of the steel industry outside the United Kingdom and the United States.

In 2022, the United States was the world’s third-largest producer of raw steel, and the sixth-largest producer of pig iron. The industry produced 29 million metric tons of pig iron and 88 million tons of steel. Most iron and steel in the United States is now made from iron and steel scrap, rather than iron ore. The United States is also a major importer of iron and steel, as well as iron and steel products.

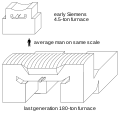

A metallurgical furnace, often simply referred to as a furnace when the context is known, is an industrial furnace used to heat, melt, or otherwise process metals. Furnaces have been a central piece of equipment throughout the history of metallurgy; processing metals with heat is even its own engineering specialty known as pyrometallurgy.