Related Research Articles

A myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is one of a group of cancers in which immature blood cells in the bone marrow do not mature, and as a result, do not develop into healthy blood cells. Early on, no symptoms typically are seen. Later, symptoms may include fatigue, shortness of breath, bleeding disorders, anemia, or frequent infections. Some types may develop into acute myeloid leukemia.

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare, autosomal recessive, genetic disease resulting in impaired response to DNA damage in the FA/BRCA pathway. Although it is a very rare disorder, study of this and other bone marrow failure syndromes has improved scientific understanding of the mechanisms of normal bone marrow function and development of cancer. Among those affected, the majority develop cancer, most often acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), MDS, and liver tumors. 90% develop aplastic anemia by age 40. About 60–75% have congenital defects, commonly short stature, abnormalities of the skin, arms, head, eyes, kidneys, and ears, and developmental disabilities. Around 75% have some form of endocrine problem, with varying degrees of severity. 60% of FA is FANC-A, 16q24.3, which has later onset bone marrow failure.

Chromosome 5q deletion syndrome is an acquired, hematological disorder characterized by loss of part of the long arm of human chromosome 5 in bone marrow myelocyte cells. This chromosome abnormality is most commonly associated with the myelodysplastic syndrome.

Dyskeratosis congenita (DKC), also known as Zinsser-Engman-Cole syndrome, is a rare progressive congenital disorder with a highly variable phenotype. The entity was classically defined by the triad of abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and leukoplakia of the oral mucosa, and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but these components do not always occur. DKC is characterized by short telomeres. The disease initially can affect the skin, but a major consequence is progressive bone marrow failure which occurs in over 80%, causing early mortality.

GATA-binding factor 1 or GATA-1 is the founding member of the GATA family of transcription factors. This protein is widely expressed throughout vertebrate species. In humans and mice, it is encoded by the GATA1 and Gata1 genes, respectively. These genes are located on the X chromosome in both species.

Reticulocytopenia is the medical term for an abnormal decrease in circulating red blood cell precursors (reticulocytes) that can lead to anemia due to resulting low red blood cell (erythrocyte) production. Reticulocytopenia may be an isolated finding or it may not be associated with abnormalities in other hematopoietic cell lineages such as those that produce white blood cells (leukocytes) or platelets (thrombocytes), a decrease in all three of these lineages is referred to as pancytopenia.

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm that features a persistent neutrophilia in peripheral blood, myeloid hyperplasia in bone marrow, hepatosplenomegaly, and the absence of the Philadelphia chromosome or a BCR/ABL fusion gene.

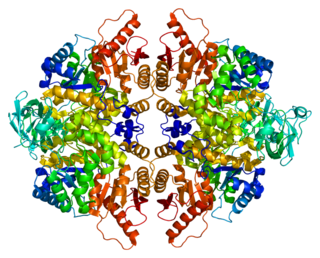

Fanconi anaemia, complementation group A, also known as FAA, FACA and FANCA, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the FANCA gene. It belongs to the Fanconi anaemia complementation group (FANC) family of genes of which 12 complementation groups are currently recognized and is hypothesised to operate as a post-replication repair or a cell cycle checkpoint. FANCA proteins are involved in inter-strand DNA cross-link repair and in the maintenance of normal chromosome stability that regulates the differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells into mature blood cells.

40S ribosomal protein S19 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RPS19 gene.

40S ribosomal protein S10 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RPS10 gene.

Ribosome maturation protein SBDS is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SBDS gene. An alternative transcript has been described, but its biological nature has not been determined. This gene has a closely linked pseudogene that is distally located. This gene encodes a member of a highly conserved protein family that exists in all archaea and eukaryotes.

Pyruvate kinase PKLR is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PKLR gene.

Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) is life-threatening leukemia in which malignant megakaryoblasts proliferate abnormally and injure various tissues. Megakaryoblasts are the most immature precursor cells in a platelet-forming lineage; they mature to promegakaryocytes and, ultimately, megakaryocytes which cells shed membrane-enclosed particles, i.e. platelets, into the circulation. Platelets are critical for the normal clotting of blood. While malignant megakaryoblasts usually are the predominant proliferating and tissue-damaging cells, their similarly malignant descendants, promegakaryocytes and megakaryocytes, are variable contributors to the malignancy.

Delta-aminolevulinate synthase 2 also known as ALAS2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ALAS2 gene. ALAS2 is an aminolevulinic acid synthase.

Congenital hypoplastic anemia is a congenital disorder that occasionally also includes leukopenia and thrombocytopenia and is characterized by deficiencies of red cell precursors.

Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS), or Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome, is a rare congenital disorder characterized by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, bone marrow dysfunction, skeletal and cardiac abnormalities and short stature. After cystic fibrosis (CF), it is the second most common cause of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in children. It is associated with the SBDS gene and has autosomal recessive inheritance.

Bone marrow failure occurs in individuals who produce an insufficient amount of red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets. Red blood cells transport oxygen to be distributed throughout the body's tissue. White blood cells fight off infections that enter the body. Bone marrow progenitor cells known as megakaryocytes produce platelets, which trigger clotting, and thus help stop the blood flow when a wound occurs.

Ribosomopathies are diseases caused by abnormalities in the structure or function of ribosomal component proteins or rRNA genes, or other genes whose products are involved in ribosome biogenesis.

Deficiency of Adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2) is a monogenic disease associated with systemic inflammation and vasculopathy that affects a wide variety of organs in different patients. As a result, it is hard to characterize a patient with this disorder. Manifestations of the disease include but are not limited to recurrent fever, livedoid rash, various cytopenias, stroke, immunodeficiency, and bone marrow failure. Symptoms often onset during early childhood, but some cases have been discovered as late as 65 years old.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kaushansky, K; Lichtman, M; Beutler, E; Kipps, T; Prchal, J; Seligsohn, U. (2010). "35". Williams Hematology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071621519.

- ↑ Tchernia, Gilbert; Delauney, J (June 2000). "Diamond–Blackfan anemia" (PDF). Orpha.net. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ↑ Pelagiadis I, et al. (2023). "The Diverse Genomic Landscape of Diamond–Blackfan Anemia: Two Novel Variants and a Mini-Review". Children. 10 (11): 1812. doi: 10.3390/children10111812 . PMC 10670567 . PMID 38002903.

- ↑ Cmejla R, Cmejlova J, Handrkova H, et al. (February 2009). "Identification of mutations in the ribosomal protein L5 (RPL5) and ribosomal protein L11 (RPL11) genes in Czech patients with Diamond–Blackfan anemia". Hum. Mutat. 30 (3): 321–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.20874 . PMID 19191325.

- ↑ Reference, Genetics Home. "Diamond-Blackfan anemia". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ "Diamond-Blackfan Anemia". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. February 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- 1 2 Boria, I; Garelli, E; Gazda, H. T.; Aspesi, A; Quarello, P; Pavesi, E; Ferrante, D; Meerpohl, J. J.; Kartal, M; Da Costa, L; Proust, A; Leblanc, T; Simansour, M; Dahl, N; Fröjmark, A. S.; Pospisilova, D; Cmejla, R; Beggs, A. H.; Sheen, M. R.; Landowski, M; Buros, C. M.; Clinton, C. M.; Dobson, L. J.; Vlachos, A; Atsidaftos, E; Lipton, J. M.; Ellis, S. R.; Ramenghi, U; Dianzani, I (2010). "The ribosomal basis of Diamond-Blackfan Anemia: Mutation and database update". Human Mutation. 31 (12): 1269–79. doi:10.1002/humu.21383. PMC 4485435 . PMID 20960466.

- 1 2 3 Ulirsch, JC; Verboon, JM; Kazerounian, S; Guo, MH; Yuan, D; Ludwig, LS; Handsaker, RE; Abdulhay, NJ; Fiorini, C; Genovese, G; Lim, ET; Cheng, A; Cummings, BB; Chao, KR; Beggs, AH; Genetti, CA; Sieff, CA; Newburger, PE; Niewiadomska, E; Matysiak, M; Vlachos, A; Lipton, JM; Atsidaftos, E; Glader, B; Narla, A; Gleizes, PE; O'Donohue, MF; Montel-Lehry, N; Amor, DJ; McCarroll, SA; O'Donnell-Luria, AH; Gupta, N; Gabriel, SB; MacArthur, DG; Lander, ES; Lek, M; Da Costa, L; Nathan, DG; Korostelev, AA; Do, R; Sankaran, VG; Gazda, HT (6 December 2018). "The Genetic Landscape of Diamond-Blackfan Anemia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (6): 930–947. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.027. PMC 6288280 . PMID 30503522.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Johns Hopkins University.

- ↑ Sankaran, Vijay G.; Ghazvinian, Roxanne; Do, Ron; Thiru, Prathapan; Vergilio, Jo-Anne; Beggs, Alan H.; Sieff, Colin A.; Orkin, Stuart H.; Nathan, David G. (2012-07-02). "Exome sequencing identifies GATA1 mutations resulting in Diamond-Blackfan anemia". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 122 (7): 2439–2443. doi:10.1172/jci63597. PMC 3386831 . PMID 22706301.

- ↑ Parrella, Sara; Aspesi, Anna; Quarello, Paola; Garelli, Emanuela; Pavesi, Elisa; Carando, Adriana; Nardi, Margherita; Ellis, Steven R.; Ramenghi, Ugo (2014-07-01). "Loss of GATA-1 full length as a cause of Diamond–Blackfan anemia phenotype". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 61 (7): 1319–1321. doi:10.1002/pbc.24944. ISSN 1545-5017. PMC 4684094 . PMID 24453067.

- ↑ Panici, B; Nakajima, H; Carlston, CM; Ozadam, H; Cenik, C; Cenik, ES (July 2021). "Loss of coordinated expression between ribosomal and mitochondrial genes revealed by comprehensive characterization of a large family with a rare Mendelian disorder". Genomics. 113 (4): 1895–1905. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.04.020. PMC 8266734 . PMID 33862179. S2CID 233277974.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoffbrand, AV; Moss PAH (2011). Essential Haematology (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9890-5.

- ↑ Gazda HT, Grabowska A, Merida-Long LB, et al. (December 2006). "Ribosomal protein S24 gene is mutated in Diamond–Blackfan anemia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (6): 1110–8. doi:10.1086/510020. PMC 1698708 . PMID 17186470.

- ↑ Cmejla R, Cmejlova J, Handrkova H, Petrak J, Pospisilova D (December 2007). "Ribosomal protein S17 gene (RPS17) is mutated in Diamond–Blackfan anemia". Hum. Mutat. 28 (12): 1178–82. doi:10.1002/humu.20608. PMID 17647292. S2CID 22482024.

- ↑ Farrar JE, Nater M, Caywood E, et al. (September 2008). "Abnormalities of the large ribosomal subunit protein, Rpl35a, in Diamond–Blackfan anemia". Blood. 112 (5): 1582–92. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-02-140012. PMC 2518874 . PMID 18535205.

- 1 2 3 Gazda H. T.; Sheen M. R.; Vlachos A.; et al. (2008). "Ribosomal protein L5 and L11 mutations are associated with cleft palate and abnormal thumbs in Diamond-Blackfan anemia patients". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 769–80. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.004. PMC 2668101 . PMID 19061985.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 603632

- 1 2 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 603701

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 604174

- 1 2 3 Gripp K W; Curry C; Olney A H; Sandoval C; Fisher J; Chong J X; UW Center for Mendelian Genomics; Pilchman L; Sahraoui R; Stabley D L; Sol-Church K (2014). "Diamond-Blackfan anemia with mandibulofacial dystostosis is heterogeneous, including the novel DBA genes TSR2 and RPS28". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 164A (9): 2240–9. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36633. PMC 4149220 . PMID 24942156.

- ↑ Gazda H, Lipton JM, Willig TN, et al. (April 2001). "Evidence for linkage of familial Diamond–Blackfan anemia to chromosome 8p23.3-p22 and for non-19q non-8p disease". Blood. 97 (7): 2145–50. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2145 . PMID 11264183.

- ↑ Williamson, MA; Snyder, LM. (2015). "Chapter 9". Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests (10th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451191769.

- ↑ Vlachos A, Klein GW, Lipton JM (2001). "The Diamond Blackfan Anemia Registry: tool for investigating the epidemiology and biology of Diamond–Blackfan anemia". J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 23 (6): 377–82. doi:10.1097/00043426-200108000-00015. PMID 11563775.

- ↑ Saunders, E. F.; Olivieri, N; Freedman, M. H. (1993). "Unexpected complications after bone marrow transplantation in transfusion-dependent children". Bone Marrow Transplantation. 12 (Suppl 1): 88–90. PMID 8374573.

- ↑ Pospisilova D, Cmejlova J, Hak J, Adam T, Cmejla R (2007). "Successful treatment of a Diamond–Blackfan anemia patient with amino acid leucine". Haematologica. 92 (5): e66–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11498 . PMID 17562599.

- ↑ Hugh W. Josephs (1936). "Anaemia of infancy and early childhood". Medicine (Baltimore). 15 (3): 307–451. doi: 10.1097/00005792-193615030-00001 .

- ↑ Diamond LK, Blackfan KD (1938). "Hypoplastic anemia". Am. J. Dis. Child. 56: 464–467.

- ↑ Diamond LK, Allen DW, Magill FB (1961). "Congenital (erythroid) hypoplastic anemia: a 25 year study". Am. J. Dis. Child. 102 (3): 403–415. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1961.02080010405019. PMID 13722603.

- ↑ Gustavsson P, Willing TN, van Haeringen A, Tchernia G, Dianzani I, Donner M, Elinder G, Henter JI, Nilsson PG, Gordon L, Skeppner G, van't Veer-Korthof L, Kreuger A, Dahl N (1997). "Diamond–Blackfan anaemia: genetic homogeneity for a gene on chromosome 19q13 restricted to 1.8 Mb". Nat. Genet. 16 (4): 368–71. doi:10.1038/ng0897-368. PMID 9241274. S2CID 6972423.

- ↑ Gustavsson P, Skeppner G, Johansson B, Berg T, Gordon L, Kreuger A, Dahl N (1997). "Diamond–Blackfan anaemia in a girl with a de novo balanced reciprocal X;19 translocation". J. Med. Genet. 34 (9): 779–82. doi:10.1136/jmg.34.9.779. PMC 1051068 . PMID 9321770.

- ↑ Draptchinskaia N, Gustavsson P, Andersson B, Pettersson M, Willig TN, Dianzani I, Ball S, Tchernia G, Klar J, Matsson H, Tentler D, Mohandas N, Carlsson B, Dahl N (1999). "The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond–Blackfan anaemia". Nat. Genet. 21 (2): 168–75. doi:10.1038/5951. PMID 9988267. S2CID 26664929.

- ↑ Gazda H, Lipton JM, Willig TN, Ball S, Niemeyer CM, Tchernia G, Mohandas N, Daly MJ, Ploszynska A, Orfali KA, Vlachos A, Glader BE, Rokicka-Milewska R, Ohara A, Baker D, Pospisilova D, Webber A, Viskochil DH, Nathan DG, Beggs AH, Sieff CA (2001). "Evidence for linkage of familial Diamond–Blackfan anemia to chromosome 8p23.3-p22 and for non-19q non-8p disease". Blood. 97 (7): 2145–50. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2145 . PMID 11264183.