A diacritic is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek διακριτικός, from διακρίνω. The word diacritic is a noun, though it is sometimes used in an attributive sense, whereas diacritical is only an adjective. Some diacritics, such as the acute ⟨ó⟩, grave ⟨ò⟩, and circumflex ⟨ô⟩, are often called accents. Diacritics may appear above or below a letter or in some other position such as within the letter or between two letters.

Kazakh or Qazaq is a Turkic language of the Kipchak branch spoken in Central Asia by Kazakhs. It is closely related to Nogai, Kyrgyz and Karakalpak. It is the official language of Kazakhstan and a significant minority language in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in Xinjiang, north-western China, and in the Bayan-Ölgii Province of western Mongolia. The language is also spoken by many ethnic Kazakhs throughout the former Soviet Union, Germany, and Turkey.

A breve is the diacritic mark ◌̆, shaped like the bottom half of a circle. As used in Ancient Greek, it is also called brachy, βραχύ. It resembles the caron but is rounded, in contrast to the angular tip of the caron. In many forms of Latin, ◌̆ is used for a shorter, softer variant of a vowel, such as "Ĭ", where the sound is nearly identical to the English /i/.

Tatar is a Turkic language spoken by the Volga Tatars mainly located in modern Tatarstan, as well as Siberia and Crimea.

Bashkir or Bashkort is a Turkic language belonging to the Kipchak branch. It is co-official with Russian in Bashkortostan. It is spoken by 1.09 million native speakers in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Estonia and other neighboring post-Soviet states, and among the Bashkir diaspora. It has three dialect groups: Southern, Eastern and Northwestern.

When used as a diacritic mark, the term dot refers to the glyphs "combining dot above", and "combining dot below" which may be combined with some letters of the extended Latin alphabets in use in a variety of languages. Similar marks are used with other scripts.

The Azerbaijani alphabet has three versions which includes the Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets.

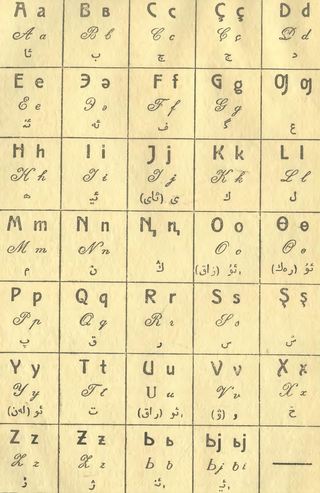

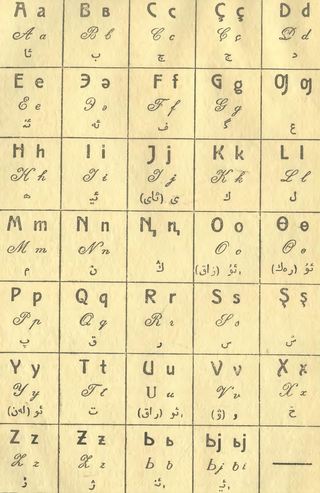

Jaꞑalif, Yangalif or Yañalif is the first Latin alphabet used during the latinisation in the Soviet Union in the 1930s for the Turkic languages. It replaced the Yaña imlâ Arabic script-based alphabet in 1928, and was replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet in 1938–1940. After their respective independence in 1991, several former Soviet states in Central Asia switched back to Latin script, with slight modifications to the original Jaꞑalif.

Karakalpak is a Turkic language spoken by Karakalpaks in Karakalpakstan. It is divided into two dialects, Northeastern Karakalpak and Southwestern Karakalpak. It developed alongside Nogai and neighbouring Kazakh languages, being markedly influenced by both. Typologically, Karakalpak belongs to the Kipchak branch of the Turkic languages, thus being closely related to and highly mutually intelligible with Kazakh and Nogai.

İske imlâ is a variant of the Arabic script, used for the Tatar language before 1920, as well as for the Old Tatar language. This alphabet can be referred to as "old" only to contrast it with Yaña imlâ.

The Common Turkic alphabet is a project of a single Latin alphabet for all Turkic languages based on a slightly modified Turkish alphabet, with 34 letters recognised by the Organization of Turkic States. Its letters are as follows:

The Ottoman Turkish alphabet is a version of the Perso-Arabic script used to write Ottoman Turkish until 1928, when it was replaced by the Latin-based modern Turkish alphabet.

Yaña imlâ was a modified variant of Arabic script that was in use for the Tatar language between 1920 and 1927. The orthographical reform modified İske imlâ, abolishing excess Arabic letters, adding letters for short vowels e, ı, ö, o. Yaña imlâ made use of "Arabic Letter Low Alef" ⟨ࢭ⟩ to indicate vowel harmony. Arguably, Yaña imlâ had as its goal the accommodation of the alphabet to the actual Tatar pronunciation.

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Greek alphabet was altered by the Etruscans, and subsequently their alphabet was altered by the Ancient Romans. Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world. It is the standard script of the English language and is often referred to simply as "the alphabet" in English. It is a true alphabet which originated in the 7th century BC in Italy and has changed continually over the last 2,500 years. It has roots in the Semitic alphabet and its offshoot alphabets, the Phoenician, Greek, and Etruscan. The phonetic values of some letters changed, some letters were lost and gained, and several writing styles ("hands") developed. Two such styles, the minuscule and majuscule hands, were combined into one script with alternate forms for the lower and upper case letters. Modern uppercase letters differ only slightly from their classical counterparts, and there are few regional variants.

The Uzbek language has been written in various scripts: Latin, Cyrillic and Arabic. The language traditionally used Arabic script, but the official Uzbek government under the Soviet Union started to use Cyrillic in 1940, which is when widespread literacy campaigns were initiated by the Soviet government across the Union. In 1992, Latin script was officially reintroduced in Uzbekistan along with Cyrillic. In the Xinjiang region of China, some Uzbek speakers write using Cyrillic, others with an alphabet based on the Uyghur Arabic alphabet. Uzbeks of Afghanistan also write the language using Arabic script, and the Arabic Uzbek alphabet is taught at some schools.

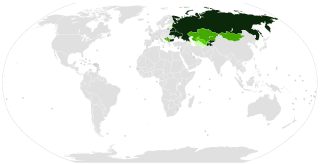

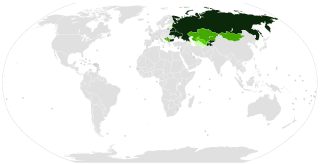

Numerous Cyrillic alphabets are based on the Cyrillic script. The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the 9th century AD and replaced the earlier Glagolitic script developed by the theologians Cyril and Methodius. It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world. The creator is Saint Clement of Ohrid from the Preslav literary school in the First Bulgarian Empire.

The Bashkir alphabet is a writing system used for the Bashkir language. Until the mid-19th century, Bashkir speakers wrote in the Türki literary language using the Arabic script. In 1869, Russian linguist Mirsalikh Bekchurin published the first guide to Bashkir grammar, and the first Cyrillic Bashkir introductory book was published by Vasily Katarinsky in Orenburg in 1892. Latinisation was first discussed in June 1924, when the first draft of the Bashkir alphabet using the Latin script was created. More reforms followed, culminating in the final version in 1938.

Dobrujan Tatar is the Tatar language of Romania. It includes Kipchak dialects, but today there is no longer a sharp distinction between the dialects and it is mostly seen as one language. This language belongs to the Kipchak Turkic languages, specifically to Kipchak-Nogai.