Manuel Lisa, also known as Manuel de Lisa, was a Spanish citizen and later, became an American citizen who, while living on the western frontier, became a land owner, merchant, fur trader, United States Indian agent, and explorer. Lisa was among the founders, in St. Louis, of the Missouri Fur Company, an early fur trading company. Manuel Lisa gained respect through his trading among Native American tribes of the upper Missouri River region, such as the Teton Sioux, Omaha and Ponca.

The Arikara War was an armed conflict between the United States, their allies from the Sioux tribe and Arikara Native Americans that took place in the summer of 1823, along the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota. It was the first Indian war west of the Missouri fought by the U.S. Army and its only conflict ever with the Arikara. The war came as a response to an Arikara attack on trappers, called "the worst disaster in the history of the Western fur trade".

Titian Ramsay Peale was an American artist, naturalist, and explorer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a scientific illustrator whose paintings and drawings of wildlife are known for their beauty and accuracy.

Stephen Harriman Long was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most prolific explorers of the early 1800s, although his career as an explorer was relatively short-lived. He covered over 26,000 miles in five expeditions, including a scientific expedition in the Great Plains area, which he famously confirmed as a "Great Desert".

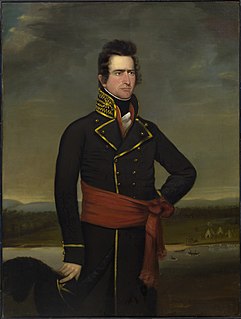

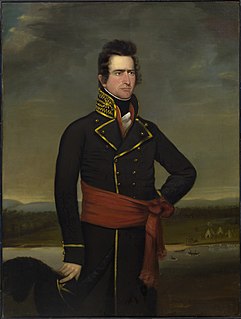

Henry Atkinson was a United States army officer serving on the western frontier, during the War of 1812, and the Yellowstone expedition. With Indian agent Benjamin O'Fallon, he negotiated a treaty with Native Americans of the upper Missouri River in 1825. Over his career in the army, he served in the western frontier, the Gulf Coast, and in New York at the border with Canada.

Fort Atkinson was the first United States Army post to be established west of the Missouri River in the unorganized region of the Louisiana Purchase of the United States. Located just east of present-day Fort Calhoun, Nebraska, the fort was erected in 1819 and abandoned in 1827. The site is now known as Fort Atkinson State Historical Park and is a National Historic Landmark. A replica fort was constructed by the state at the site during the 1980s–1990s.

Cabanne's Trading Post was established in 1822 by the American Fur Company as Fort Robidoux near present-day Dodge Park in North Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was named for the influential fur trapper Joseph Robidoux. Soon after it was opened, the post was called the French Company or Cabanné's Post, for the ancestry and name of its operator, Jean Pierre Cabanné, who was born and raised among the French community of St. Louis, Missouri.

Fort Lisa (1812–1823) was established in 1812 in what is now North Omaha in Omaha, Nebraska by famed fur trader Manuel Lisa and the Missouri Fur Company, which was based in Saint Louis. The fort was associated with several firsts in Nebraska history: Lisa was the first European farmer in Nebraska; it was the first settlement by American citizens set up in the then-recent Louisiana Purchase; Lisa's wife was the first woman resident of European descent in Nebraska; and the first steamboat to navigate Nebraska waters, the Western Engineer, arrived at Fort Lisa in September 1819.

Thomas Biddle was an American military hero during the War of 1812. Biddle is better known though for having been killed in a duel with Missouri Congressman Spencer Pettis.

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 explored the region of northwestern Wyoming that later became Yellowstone National Park in 1872. It was led by geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden. The 1871 survey was not Hayden's first, but it was the first federally funded geological survey to explore and further document features in the region soon to become Yellowstone National Park, and played a prominent role in convincing the U.S. Congress to pass the legislation creating the park. In 1894, Nathaniel P. Langford, the first park superintendent and a member of the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition which explored the park in 1870, wrote this about the Hayden expedition:

We trace the creation of the park from the Folsom-Cook expedition of 1869 to the Washburn expedition of 1870, and thence to the Hayden expedition of 1871, Not to one of these expeditions more than to another do we owe the legislation which set apart this "pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people"

Edwin P. James, a 19th-century American botanist, geologist, linguist, and medical practitioner, was an important figure in the early exploration of the American West. James was also known for his time spent creating relationships with Native Americans in the United States, and also aiding African Americans to escape slavery.

The Missouri Fur Company was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under various names from 1809 until its final dissolution in 1830. It was created by a group of fur traders and merchants from St. Louis and Kaskaskia, Illinois, including Manuel Lisa and members of the Chouteau family. Its expeditions explored the upper Missouri River and traded with a variety of Native American tribes, and it acted as the prototype for fur trading companies along the Missouri River until the 1820s.

The Yellowstone expedition was an expedition to the American frontier in 1819 and 1820 authorized by United States Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, with the goal of establishing a military fort or outpost at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in present-day North Dakota. Sometimes called the Atkinson–Long Expedition after its two principal leaders, Colonel Henry Atkinson and Major Stephen Harriman Long, it led to the creation of Fort Atkinson in present-day Nebraska, the first United States Army post established west of the Missouri River, but was otherwise a costly failure, stalling near Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Old Baldy, also known as the Tower, is a hill located near the village of Lynch, in Boyd County, in the northern part of the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. It was visited by the Lewis and Clark Expedition on their way up the Missouri River in 1804; nearby, they discovered a colony of prairie dogs, an animal previously unknown to scientists.

Columbia Fur Company was a fur trading and Indian trading business active from 1821 to 1827, in Michigan Territory and in the unorganized territory of the United States. It then became the Upper Missouri Outfit of the American Fur Company.

Joseph Bijeau, also known as Joseph Bijeau dit Bissonet and Joseph Bissonet, was among the earliest fur trappers of the Rocky Mountains. He was a guide for Stephen Harriman Long's expedition of the Great Plains in 1820. A fur trapper and hunter, he lived among the Pawnee people. He was able to communicate to a number of Native American tribes through his use of sign language as well as the Crow language, which was used among a number of western tribes. After Spain lost the Mexican territory, trappers like Bijeau moved to Taos where they could trap, trade, and travel east without the hostilities that they experienced in the western United States.

The Stephen H. Long Expedition of 1820 traversed America's Great Plains and up to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. It was the first scientific party hired by the United States government to explore the West. Lewis and Clark (1803–1806) and Zebulon Pike (1805–1807) explored the western frontier but they were primarily military expeditions. A group of scientists traveled to St. Louis and on to Council Bluff (Nebraska) for the Yellowstone expedition of the upper Missouri River that would have established a number of military posts. The expensive effort was cancelled following a financial crash, steamboat failures, operational scandals, and negotiation of the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, which changed the border between New Spain and the United States. The scientists were reassigned to an expedition led by Stephen Harriman Long. From June 6 to September 13, 1820, Long and fellow scientists traveled across the Great Plains beginning at the Missouri River near present Omaha, Nebraska, along the Platte River to the Front Range, and east along the Arkansas and Canadian Rivers of Colorado and Oklahoma. The expedition terminated at Fort Smith in Arkansas. They recorded many new species of plants, insects, and animals. Long termed the land the Great American Desert.

Benjamin O'Fallon (1793–1842) was an Indian agent along the upper areas of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. He interacted with Native Americans as a trader and Indian agent. He was against British trappers and traders operating in the United States and territories. He believed that the military should have taken a strong stance against the British and firm in negotiations with Native Americans. Despite his brash manner and contention with the military, he was able to negotiate treaties between native and white Americans. In his early and later careers, he built gristmills, was a retailer, and a planter. He collected Native American artifacts and paintings of tribe members by George Catlin. His uncle William Clark was his guardian and financial backer.

Samuel Seymour was a painter, engraver, and illustrator who documented Native American people and the scenery from expeditions of Stephen Harriman Long in 1819, 1820, and 1823. Some of the drawings captured new species of flora and fauna.

The paddle steamer Western Engineer was the first steamboat on the Missouri River. It was purpose built after a design by Major Stephen Harriman Long by the Allegheny Arsenal in Pittsburgh, for the scientific party of the Yellowstone expedition which Major Long commanded. The paddle wheel was placed in the stern, the steam engine hidden below the waterline, the vessel was heavily armed and had acquired a peculiar appearance intended to inspire fear and awe among the Plains Indians. Her first voyage took her from Pittsburgh to Saint Louis in 1819. The second voyage took her to Fort Lisa, Nebraska the same year. The third voyage took her back to Saint Louis in the spring of 1820, while the fourth voyage was a charting expedition up the Mississippi to the Des Moines Rapids and down to Cape Girardeau, Missouri. A fifth voyage supposed to take her back to Pittsburgh had to be aborted at Smithland, Kentucky due to low water, and she was left there.