Domitian was Roman emperor from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavian dynasty. Described as "a ruthless but efficient autocrat", his authoritarian style of ruling put him at sharp odds with the Senate, whose powers he drastically curtailed.

The 1st century was the century spanning AD 1 through AD 100 (C) according to the Julian calendar. It is often written as the 1st century AD or 1st century CE to distinguish it from the 1st century BC which preceded it. The 1st century is considered part of the Classical era, epoch, or historical period. The Roman Empire, Han China and the Parthian Persia were the most powerful and hegemonic states.

The 70s was a decade that ran from January 1, AD 70, to December 31, AD 79.

The 90s was a decade that ran from January 1, AD 90, to December 31, AD 99.

Titus Caesar Vespasianus was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor to succeed his biological father.

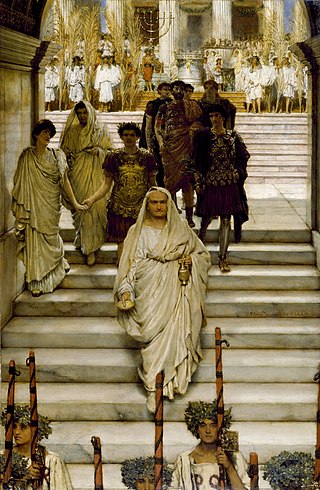

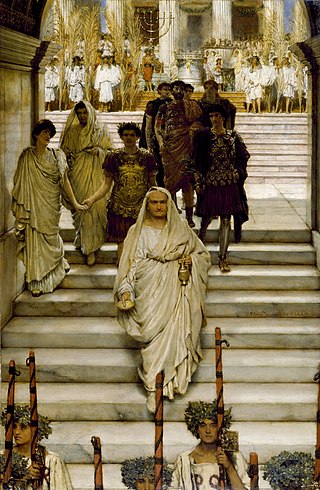

The Flavian dynasty, lasting from AD 69 to 96, was the second dynastic line of emperors to rule the Roman Empire following the Julio-Claudians, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian. The Flavians rose to power during the civil war of AD 69, known as the Year of the Four Emperors; after Galba and Otho died in quick succession, Vitellius became emperor in mid 69. His claim to the throne was quickly challenged by legions stationed in the eastern provinces, who declared their commander Vespasian emperor in his place. The Second Battle of Bedriacum tilted the balance decisively in favor of the Flavian forces, who entered Rome on 20 December, and the following day, the Roman Senate officially declared Vespasian emperor, thus commencing the Flavian dynasty. Although the dynasty proved to be short-lived, several significant historic, economic and military events took place during their reign.

Rabbinic Judaism, also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Rabbanite Judaism, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian Talmud. Rabbinic Judaism has its roots in the Pharisaic school of Second Temple Judaism, and is based on the belief that Moses at Mount Sinai received both the Written Torah and the Oral Torah from God. The Oral Torah, transmitted orally, explains the Written Torah. At first, it was forbidden to write down the Oral Torah, but after the destruction of the Second Temple, it was decided to write it down in the form of the Talmud and other rabbinic texts for the sake of preservation.

The Jewish–Roman wars were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of Judaea and the Eastern Mediterranean against the Roman Empire between 66 and 135 CE. The First Jewish–Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt were nationalist rebellions, striving to restore an independent Judean state, while the Kitos War was more of an ethno-religious conflict, mostly fought outside the province of Judaea. As a result, there is variation in the use of the term "Jewish-Roman wars." Some sources exclusively apply it to the First Jewish-Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt, while others include the Kitos War as well.

The Siege of Jerusalem of 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War, in which the Roman army led by future emperor Titus besieged Jerusalem, the center of Jewish rebel resistance in the Roman province of Judaea. Following a five-month siege, the Romans destroyed the city and the Second Jewish Temple.

Fiscus was the treasury of the Roman Empire. It was initially the personal wealth of the emperors, funded by taxation on the imperial provinces, assumption of estates and other privileges. By the third century it was understood as a state fund rather than a personal one, albeit under the emperor's control. It is the origin of the English term "fiscal."

Judaea was a Roman province from 6 to 132 AD, which incorporated the Levantine regions of Judea, Samaria and Idumea, extending over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Judea. The name Judaea was derived from the Iron Age Kingdom of Judah.

As the Roman Republic, and later the Roman Empire, expanded, it came to include people from a variety of cultures, and religions. The worship of an ever increasing number of deities was tolerated and accepted. The government, and the Romans in general, tended to be tolerant towards most religions and religious practices. Some religions were banned for political reasons rather than dogmatic zeal, and other rites which involved human sacrifice were banned.

Anti-Judaism is a term which is used to describe a range of historic and current ideologies which are totally or partially based on opposition to Judaism, on the denial or the abrogation of the Mosaic covenant, and the replacement of Jewish people by the adherents of another religion, political theology, or way of life which is held to have superseded theirs as the "light to the nations" or God's chosen people. The opposition is maintained by the adaptation of Jewish prophecy and texts. According to David Nirenberg there have been Christian, Islamic, nationalistic, Enlightenment rationalist, and socio-economic variations of this theme.

Anti-Judaism in Early Christianity is a description of anti-Judaic sentiment in the first three centuries of Christianity; the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd centuries. Early Christianity is sometimes considered as Christianity before 325 when the First Council of Nicaea was convoked by Constantine the Great, although it is not unusual to consider 4th and 5th century Christianity as members of this category as well.

Taxation of the Jews in Europe refers to taxes imposed specifically on Jews in Europe, in addition to the taxes levied on the general population. Special taxation imposed on the Jews by the state or ruler of the territory in which they were living has played an important part in Jewish history. The abolition of special taxes on the Jews followed their admission to civil rights in France and elsewhere in Europe at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries.

Nerva was a Roman emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor when aged almost 66, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the succeeding rulers of the Flavian dynasty. Under Nero, he was a member of the imperial entourage and played a vital part in exposing the Pisonian conspiracy of 65. Later, as a loyalist to the Flavians, he attained consulships in 71 and 90 during the reigns of Vespasian and Domitian, respectively. On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy involving members of the Praetorian Guard and several of his freedmen. On the same day, Nerva was declared emperor by the Roman Senate. As the new ruler of the Roman Empire, he vowed to restore liberties which had been curtailed during the autocratic government of Domitian.

The Roman historian Suetonius mentions early Christians and may refer to Jesus Christ in his work Lives of the Twelve Caesars. One passage in the biography of the Emperor Claudius Divus Claudius 25, refers to agitations in the Roman Jewish community and the expulsion of Jews from Rome by Claudius during his reign, which may be the expulsion mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles. In this context "Chresto" is mentioned. Some scholars see this as a likely reference to Jesus, while others see it as referring to another person living in Rome, of whom we have no information.

The Temple tax was a tax paid by Israelites and Levites which went towards the upkeep of the Jewish Temple, as reported in the New Testament. Traditionally, Kohanim were exempt from the tax.

During the Byzantine period, in the years between Constantine the Great's rise to power and the conquest of Jerusalem by the Rashidun Caliphate in 637, Jerusalem was under the control of the Byzantine Empire. The essential change in the character and status of the city, compared to the Roman period, was its transformation from a pagan city to a Christian city. The Byzantine rule developed the Roman colony Aelia Capitolina in Jerusalem, turning it into a central Christian city from a religious and administrative point of view and a world center for pilgrimage. At the end of the period, between the years 614–628, Jerusalem was conquered by the Sasanian Empire, but was later recaptured by Byzantine Christians in 629 CE. Jerusalem was captured by the Rashidun Caliphate in 637 CE as part of the Siege of Jerusalem (636–637).