St. Elizabeths Hospital is a psychiatric hospital in Southeast Washington, D.C. operated by the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health. The hospital opened in 1855 under the name Government Hospital for the Insane, the first federally operated psychiatric hospital in the United States.

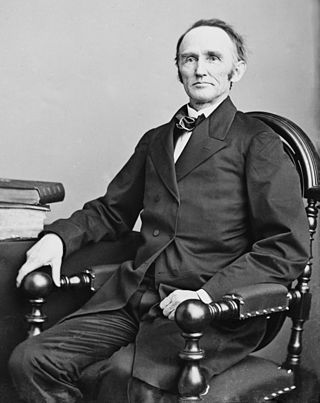

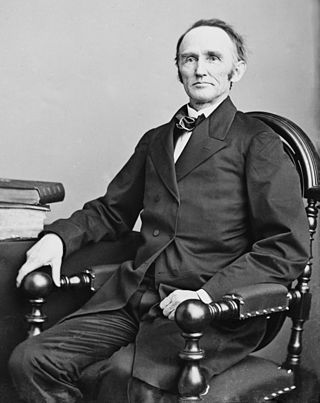

Montgomery Blair was an American politician and lawyer from Maryland. He served in the Lincoln administration cabinet as Postmaster-General from 1861 to 1864, during the Civil War. He was the son of Francis Preston Blair, elder brother of Francis Preston Blair Jr. and cousin of B. Gratz Brown.

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, S.E., in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national memory" founded before the Civil War. Over 65,000 individuals are buried or memorialized at the cemetery, including many who helped form the nation and Washington, D.C. in the early 19th century.

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs was a career United States Army officer and military and civil engineer, who served as Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army during and after the American Civil War. Although a Southerner from Georgia, Meigs strongly opposed secession and supported the Union. His record as Quartermaster General was regarded as outstanding, both in effectiveness and in ethical probity, and Secretary of State William H. Seward viewed Meigs' leadership and contributions as key factors in the Union victory in the war.

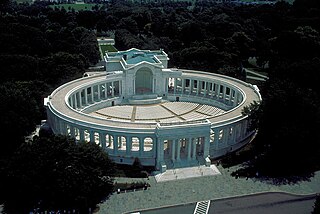

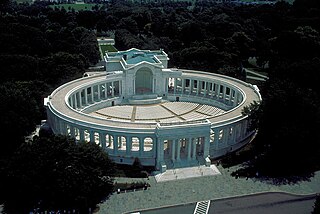

Memorial Amphitheater is an outdoor amphitheater, exhibit hall, and nonsectarian chapel located in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, in the United States. It was designed in 1913 as a replacement for the older, wooden amphitheater near Arlington House. Ground was broken for its construction in March 1915 and it was dedicated in May 1920. In the center of its eastern steps is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, dedicated in 1921. It has served as the site for numerous Veterans Day and Memorial Day events, as well as for memorial services and funerals for many individuals.

Constantino Brumidi was an Italian painter and a naturalised American citizen, best known and honored for his fresco work, Apotheosis of Washington, in the Capitol Building in Washington, DC.

Glenwood Cemetery is located in Houston, Texas, United States. Developed in 1871, the first professionally designed cemetery in the city accepted its first burial in 1872. Its location at Washington Avenue overlooking Buffalo Bayou served as an entertainment attraction in the 1880s. The design was based on principles for garden cemeteries, breaking the pattern of the typical gridiron layouts of most Houston cemeteries. Many influential people lay to rest at Glenwood, making it the "River Oaks of the dead." As of 2018, Glenwood includes the annexed property of the adjacent Washington Cemetery, creating a total area of 84 acres (34 ha) with 18 acres (7.3 ha) still undeveloped.

Mount Olivet Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 1300 Bladensburg Road, NE in Washington, D.C. It is maintained by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington. The largest Catholic burial ground in the District of Columbia, it was one of the first in the city to be racially integrated.

Oak Hill Cemetery is a historic 22-acre (8.9 ha) cemetery located in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was founded in 1848 and completed in 1853, and is a prime example of a rural cemetery. Many famous politicians, business people, military people, diplomats, and philanthropists are buried at Oak Hill, and the cemetery has a number of Victorian-style memorials and monuments. Oak Hill has two structures which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places: the Oak Hill Cemetery Chapel and the Van Ness Mausoleum.

Somerville Cemetery refers to two cemeteries located in Somerville, New Jersey, in the United States. The "Old Cemetery" was founded about 1813, but its small size meant that it quickly filled. In 1867, the "New Cemetery" was founded across Bridge Street from the Old Cemetery. The New Cemetery has a large African American section, an artifact of an era in which burials were often segregated by race.

The Frankfort Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located on East Main Street in Frankfort, Kentucky. The cemetery is the burial site of Daniel Boone, the famed frontiersman, and contains the graves of other famous Americans including seventeen Kentucky governors and a Vice President of the United States.

William Embre Gaines was a U.S. Representative from Virginia.

Prospect Hill Cemetery, also known as the German Cemetery, is a historic German-American cemetery founded in 1858 and located at 2201 North Capitol Street in Washington, D.C. From 1886 to 1895, the Prospect Hill Cemetery board of directors battled a rival organization which illegally attempted to take title to the grounds and sell a portion of them as building lots. From 1886 to 1898, the cemetery also engaged in a struggle against the District of Columbia and the United States Congress, which wanted construct a main road through the center of the cemetery. This led to the passage of an Act of Congress, the declaration of a federal law to be unconstitutional, the passage of a second Act of Congress, a second major court battle, and the declaration by the courts that the city's eminent domain procedures were unconstitutional. North Capitol Street was built, and the cemetery compensated fairly for its property.

Glenwood Cemetery Mortuary Chapel is a historic chapel located in Glenwood Cemetery in Northeast, Washington, D.C.

Columbian Harmony Cemetery was an African-American cemetery that formerly existed at 9th Street NE and Rhode Island Avenue NE in Washington, D.C., in the United States. Constructed in 1859, it was the successor to the smaller Harmoneon Cemetery in downtown Washington. All graves in the cemetery were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland, in 1959. The cemetery site was sold to developers, and a portion used for the Rhode Island Avenue – Brentwood Washington Metro station.

National Harmony Memorial Park is a private, secular cemetery located at 7101 Sheriff Road in Landover, Maryland, in the United States. Although racially integrated, most of the individuals interred there are African American. In 1960, the 37,000 graves of Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Washington, D.C., were transferred to National Harmony Memorial Park's Columbian Harmony section. In 1966, about 2,000 graves from Payne's Cemetery in D.C. were transferred to National Harmony Memorial Park as well.

Glenn Brown (1854–1932) was an American architect and historian.

Glenwood Memorial Gardens is a 70-acre lawn cemetery in Broomall, Pennsylvania. It was originally established in 1849 as a rural cemetery on 20 acres in North Philadelphia as Glenwood Cemetery. Over 700 Union and Confederate soldiers who died in local hospitals during the American Civil War were buried in Glenwood cemetery. The soldiers' remains were moved to the Philadelphia National Cemetery in 1891.

Abbey Mausoleum was a mausoleum in Arlington County, Virginia, in the United States founded in 1924. One of the most luxurious burial places in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, many famous individuals, judges, and military leaders were buried there. The mausoleum encountered financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in 1966. It suffered vandalism numerous times, and several graves were desecrated. Remains buried there were disinterred and reburied elsewhere, and it was demolished in February 2001. Several architectural features of the structure were salvaged. It was located just outside Arlington National Cemetery next to Henderson Hall.

The Presbyterian Burying Ground, also known as the Old Presbyterian Burying Ground, was a historic cemetery which existed between 1802 and 1909 in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was one of the most prominent cemeteries in the city until the 1860s. Burials there tapered significantly after Oak Hill Cemetery was founded nearby in 1848. The Presbyterian Burying Ground closed to new burials in 1887, and about 500 to 700 bodies were disinterred after 1891 when an attempt was made to demolish the cemetery and use the land for housing. The remaining graves fell into extensive disrepair. After a decade of effort, the District of Columbia purchased the cemetery in 1909 and built Volta Park there, leaving nearly 2,000 bodies buried at the site. Occasional human remains and tombstones have been discovered at the park since its construction. A number of figures important in the early history of Georgetown and Washington, D.C., military figures, politicians, merchants, and others were buried at Presbyterian Burying Ground.