Flanders is the Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, language, politics, and history, and sometimes involving neighbouring countries. The demonym associated with Flanders is Fleming, while the corresponding adjective is Flemish, which can also refer to the collective of Dutch dialects spoken in that area, or more generally the Belgian variant of Standard Dutch. The official capital of Flanders is the City of Brussels, although the Brussels-Capital Region that includes it has an independent regional government. The powers of the government of Flanders consist, among others, of economic affairs in the Flemish Region and the community aspects of Flanders life in Brussels, such as Flemish culture and education.

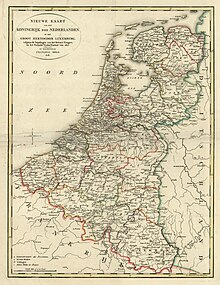

The Seventeen Provinces were the Imperial states of the Habsburg Netherlands in the 16th century. They roughly covered the Low Countries, i.e., what is now the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and most of the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais (Artois). Also within this area were semi-independent fiefdoms, mainly ecclesiastical ones, such as Liège, Cambrai and Stavelot-Malmedy.

The Flemish Movement is an umbrella term which encompasses various political groups in the Belgian region of Flanders and, less commonly, in French Flanders. Ideologically, it encompasses groups which have sought to promote Flemish culture and the Dutch language as well as those seeking greater political autonomy for Flanders within Belgium. It also encompassed nationalists who seek the secession of Flanders from Belgium, either through outright independence or unification with the Netherlands.

The Flemish Region, usually simply referred to as Flanders, is one of the three regions of Belgium—alongside the Walloon Region and the Brussels-Capital Region. Covering the northern portion of the country, the Flemish Region is primarily Dutch-speaking. With an area of 13,522 km2 (5,221 sq mi), it accounts for only 45% of Belgium's territory, but 57% of its population. It is one of the most densely populated regions of Europe with around 490/km2 (1,300/sq mi).

The Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond, widely known by its acronym VNV, was a Flemish nationalist political party active in Belgium between 1933 and 1945. It became the leading force of political collaboration in Flanders during the German occupation of Belgium in World War II. Authoritarian by inclination, the party advocated the creation of a "Greater Netherlands" (Dietsland) combining Flanders and the Netherlands.

The Dutch are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands. They share a common ancestry and culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Aruba, Suriname, Guyana, Curaçao, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and the United States. The Low Countries were situated around the border of France and the Holy Roman Empire, forming a part of their respective peripheries and the various territories of which they consisted had become virtually autonomous by the 13th century. Under the Habsburgs, the Netherlands were organised into a single administrative unit, and in the 16th and 17th centuries the Northern Netherlands gained independence from Spain as the Dutch Republic. The high degree of urbanisation characteristic of Dutch society was attained at a relatively early date. During the Republic the first series of large-scale Dutch migrations outside of Europe took place.

Pieter Catharinus Arie Geyl was a Dutch historian, well known for his studies in early modern Dutch history and in historiography.

Verdinaso, sometimes rendered as Dinaso, was a small fascist political movement active in Belgium and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands between 1931 and 1941.

The Kingdom of Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French, and German.

The Francization of Brussels refers to the evolution, over the past two centuries, of this historically Dutch-speaking city into one where French has become the majority language and lingua franca. The main cause of this transition was the rapid, compulsory assimilation of the Flemish population, amplified by immigration from France and Wallonia.

Dutch is a West Germanic language spoken by about 25 million people as a first language and 5 million as a second language. It is the third most widely spoken Germanic language, after its close relatives English and German. Afrikaans is a separate but mutually intelligible sister language of modern Dutch, and a daughter language of an earlier form of Dutch. It is spoken, to some degree, by at least 16 million people, mainly in South Africa and Namibia, evolving from the Cape Dutch dialects of Southern Africa. The dialects used in Belgium and in Suriname, meanwhile, are all guided by the Dutch Language Union.

Orangism was a political tradition in Belgium that supported its reintegration into the short-lived United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1830) under the rule of the Dutch House of Orange. It existed principally in the 1830s and 1840s.

Flemish people or Flemings are a Germanic ethnic group native to Flanders, Belgium, who speak Flemish Dutch. Flemish people make up the majority of Belgians, at about 60%.

Flemish (Vlaams) is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch, Belgian Dutch, or Southern Dutch. Flemish is native to the region known as Flanders in northern Belgium; it is spoken by Flemings, the dominant ethnic group of the region. Outside of Belgium Flanders, it is also spoken to some extent in French Flanders and the Dutch Zeelandic Flanders.

The Dutch language used in Belgium can also be referred to as Flemish Dutch or Belgian Dutch. Dutch is the mother tongue of about 60% of the population in Belgium, spoken by approximately 6.5 million out of a population of 11 million people. It is the only official language in Flanders, that is to say the provinces of Antwerp, Flemish Brabant, Limburg, East Flanders and West Flanders. Alongside French, it is also an official language of Brussels. However, in the Brussels Capital Region and in the adjacent Flemish-Brabant municipalities, Dutch has been largely displaced by French as an everyday language.

The Humanistisch Verbond is a Dutch association based on secular humanist principles.

Anarchism in the Netherlands originated in the second half of the 19th century. Its roots lay in the radical and revolutionary ideologies of the labor movement, in anti-authoritarian socialism, the free thinkers and in numerous associations and organizations striving for a libertarian form of society. During the First World War, individuals and groups of syndicalists and anarchists of various currents worked together for conscientious objection and against government policies. The common resistance was directed against imperialism and militarism.

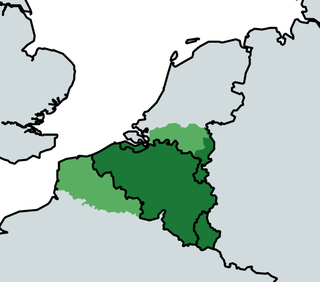

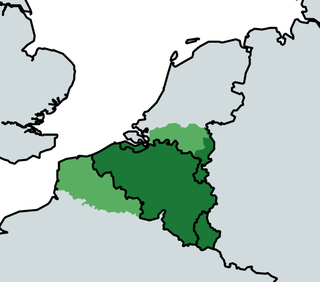

Greater Belgium is a Belgian irredentist concept which lays claim on territory nationalists deem as rightfully Belgian. It usually laid claim to: German territory historically belonging to the former Duchy of Limburg (Eupen-Malmedy), Dutch Limburg, Zeelandic Flanders, and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. To a lesser degree, they also claimed the Dutch province of North Brabant and the French Netherlands (Nord-Pas-de-Calais). Shortly after the Belgian Revolution, some groups even proposed a Belgo-Rhine federation. Nowadays, belief in Belgian irredentism is very uncommon and overshadowed by talk of partitioning Belgium or the incorporation of Flanders into the Netherlands.

Lucien Leopold Joseph Jottrand was a Belgian-Walloon lawyer, politician, progressive Flamingant and Pan-Netherlander. He was member of the National Congress of Belgium shortly after the de facto independence of Belgium and held a unique position in the young Flemish Movement.

Pan-Netherlands, sometimes translated as Whole-Netherlands, is an irredentist concept which aims to unite the Low Countries into a single state. It is an example of Pan-Nationalism.