Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs | |

Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, November 2010 | |

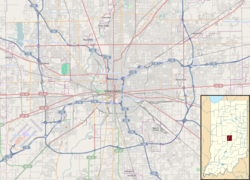

| Location | 2034 North Capitol Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°47′37″N86°9′42″W / 39.79361°N 86.16167°W |

| Area | 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) |

| Built | 1897 |

| Built by | Shellhouse & Co. |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 87000512 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 7, 1987 |

Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, also known as the Minor House, is a historic National Association of Colored Women's Clubs clubhouse in Indianapolis, Indiana. The two-and-one-half-story "T"-plan building was originally constructed in 1897 as a private dwelling for John and Sarah Minor; however, since 1927 it has served as the headquarters of the Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, a nonprofit group of African American women. The Indiana federation was formally organized on April 27, 1904, in Indianapolis and incorporated in 1927. The group's Colonial Revival style frame building sits on a brick foundation and has a gable roof with hipped dormers. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

Contents

- Club history

- Founding in Indianapolis

- Activities and leadership

- Membership

- Building history and description

- See also

- Notes

- References

Local newspaper columnist Lillian Thomas Fox of Indianapolis served as the federation's state organizer and honorary president. The Indiana group became an affiliate of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, which was formed in 1896. The state federation organized local clubs of black clubwomen, hosted annual state conventions, published a monthly newsletter, sponsored fund-raising activities, and established a scholarship fund. It also shared information on social issues facing Indiana's black community. By 1924 the Indiana federation had eighty-nine clubs with a combined membership of 1,670, but membership has declined in recent decades. Sallie Wyatt Stewart of Evansville, Indiana, who served as the Indiana federation's third president (1921–28), succeeded Mary McLeod Bethune as president of the NACWC in 1928.