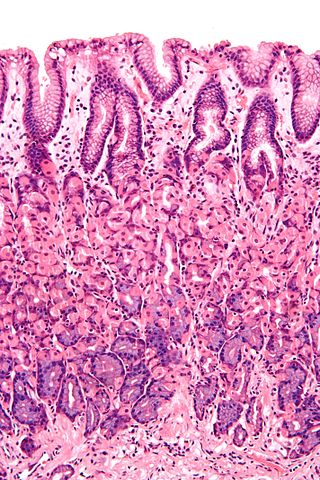

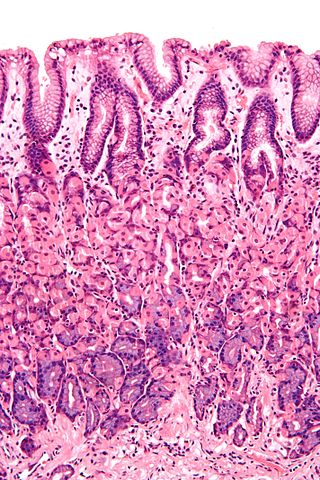

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is mostly of endodermal origin and is continuous with the skin at body openings such as the eyes, eyelids, ears, inside the nose, inside the mouth, lips, the genital areas, the urethral opening and the anus. Some mucous membranes secrete mucus, a thick protective fluid. The function of the membrane is to stop pathogens and dirt from entering the body and to prevent bodily tissues from becoming dehydrated.

The gastrointestinal tract is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and other animals, including the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Food taken in through the mouth is digested to extract nutrients and absorb energy, and the waste expelled at the anus as faeces. Gastrointestinal is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the stomach and intestines.

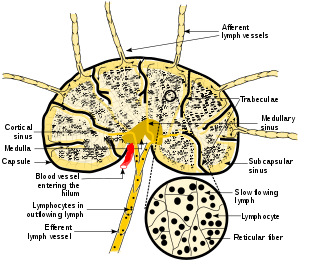

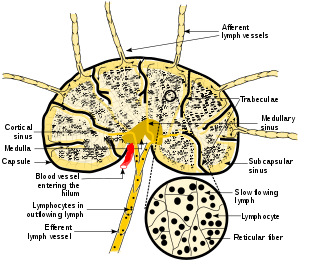

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lymphatic tissue and lymph. Lymph is a clear fluid carried by the lymphatic vessels back to the heart for re-circulation. The Latin word for lymph, lympha, refers to the deity of fresh water, "Lympha".

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that include B and T cells. Lymph nodes are important for the proper functioning of the immune system, acting as filters for foreign particles including cancer cells, but have no detoxification function.

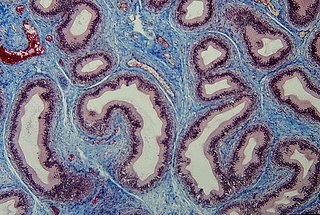

The ileum is the final section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear and the terms posterior intestine or distal intestine may be used instead of ileum. Its main function is to absorb vitamin B12, bile salts, and whatever products of digestion that were not absorbed by the jejunum.

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops mostly from the mesenchyme, derived from the mesoderm, the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tissue is found in between other tissues everywhere in the body, including the nervous system. The three meninges, membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord, are composed of connective tissue. Most types of connective tissue consists of three main components: elastic and collagen fibers, ground substance, and cells. Blood, and lymph are classed as specialized fluid connective tissues that do not contain fiber. All are immersed in the body water. The cells of connective tissue include fibroblasts, adipocytes, macrophages, mast cells and leukocytes.

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial (mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of many internal organs, the corresponding inner surfaces of body cavities, and the inner surfaces of blood vessels. Epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. These tissues also lack blood or lymph supply. The tissue is supplied by nerves.

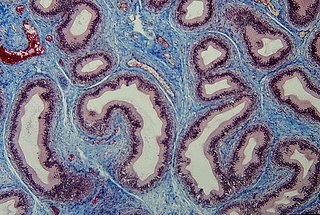

Peyer's patches are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer. They are an important part of gut associated lymphoid tissue usually found in humans in the lowest portion of the small intestine, mainly in the distal jejunum and the ileum, but also could be detected in the duodenum.

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. It comprises stratified squamous epithelium, termed "oral epithelium", and an underlying connective tissue termed lamina propria. The oral cavity has sometimes been described as a mirror that reflects the health of the individual. Changes indicative of disease are seen as alterations in the oral mucosa lining the mouth, which can reveal systemic conditions, such as diabetes or vitamin deficiency, or the local effects of chronic tobacco or alcohol use. The oral mucosa tends to heal faster and with less scar formation compared to the skin. The underlying mechanism remains unknown, but research suggests that extracellular vesicles might be involved.

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is a component of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) which works in the immune system to protect the body from invasion in the gut.

The mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), also called mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue, is a diffuse system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue found in various submucosal membrane sites of the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, nasopharynx, thyroid, breast, lung, salivary glands, eye, and skin. MALT is populated by lymphocytes such as T cells and B cells, as well as plasma cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, each of which is well situated to encounter antigens passing through the mucosal epithelium. The appendix, long misunderstood as a vestigial organ, is now recognized as a key MALT structure, playing an essential role in B-lymphocyte-mediated immune responses, hosting extrathymically derived T-lymphocytes, regulating pathogens through its lymphatic vessels, and potentially producing early defenses against diseases. In the case of intestinal MALT, M cells are also present, which sample antigen from the lumen and deliver it to the lymphoid tissue. MALT constitute about 50% of the lymphoid tissue in human body. Immune responses that occur at mucous membranes are studied by mucosal immunology.

The muscularis mucosae is a thin layer of muscle of the gastrointestinal tract, located outside the lamina propria, and separating it from the submucosa. It is present in a continuous fashion from the esophagus to the upper rectum. A discontinuous muscularis mucosae–like muscle layer is present in the urinary tract, from the renal pelvis to the bladder; as it is discontinuous, it should not be regarded as a true muscularis mucosae.

Microfold cells are found in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of the Peyer's patches in the small intestine, and in the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) of other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. These cells are known to initiate mucosal immunity responses on the apical membrane of the M cells and allow for transport of microbes and particles across the epithelial cell layer from the gut lumen to the lamina propria where interactions with immune cells can take place.

The submucosa is a thin layer of tissue in various organs of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and genitourinary tracts. It is the layer of dense irregular connective tissue that supports the mucosa and joins it to the muscular layer, the bulk of overlying smooth muscle.

In anatomy and histology, the term wandering cell is used to describe cells that are found in connective tissue, but are not fixed in place. This term is used occasionally and usually refers to blood leukocytes in particular mononuclear phagocytes. Frequently, the term refers to circulating macrophages and has been used also for stationary macrophages fixed in tissues (histiocytes), which are sometimes referred to as "resting wandering cells".

The gastric mucosa is the mucous membrane layer of the stomach, which contains the gastric pits, to which the gastric glands empty. In humans, it is about one mm thick, and its surface is smooth, soft, and velvety. It consists of simple secretory columnar epithelium, an underlying supportive layer of loose connective tissue called the lamina propria, and the muscularis mucosae, a thin layer of muscle that separates the mucosa from the underlying submucosa.

Histology is the study of the minute structure, composition, and function of tissues. Mature human vocal cords are composed of layered structures which are quite different at the histological level.

Mucosal immunology is the study of immune system responses that occur at mucosal membranes of the intestines, the urogenital tract, and the respiratory system. The mucous membranes are in constant contact with microorganisms, food, and inhaled antigens. In healthy states, the mucosal immune system protects the organism against infectious pathogens and maintains a tolerance towards non-harmful commensal microbes and benign environmental substances. Disruption of this balance between tolerance and deprivation of pathogens can lead to pathological conditions such as food allergies, irritable bowel syndrome, susceptibility to infections, and more.

The gastrointestinal wall of the gastrointestinal tract is made up of four layers of specialised tissue. From the inner cavity of the gut outwards, these are the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscular layer and the serosa or adventitia.

Anatomical terminology is used to describe microanatomical structures. This helps describe precisely the structure, layout and position of an object, and minimises ambiguity. An internationally accepted lexicon is Terminologia Histologica.