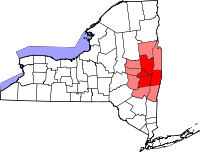

Bethlehem is a town in Albany County, New York, United States. The town's population was 35,034 at the 2020 census. Bethlehem is located immediately to the south of the city of Albany and includes the following hamlets: Delmar, Elsmere, Glenmont, North Bethlehem, Selkirk, Slingerlands, and South Bethlehem. U.S. Route 9W passes through the town. The town is named after the biblical Bethlehem. A notable person from this city is YouTuber James Charles.

Delmar is a hamlet in the Town of Bethlehem, in Albany County, New York, United States. It is a suburb of the neighboring city of Albany. The community is bisected by NY Route 443, a major thoroughfare, main street, and route to Albany.

Guilderland is a town in Albany County, New York, United States. In the 2020 census, the town had a population of 36,848. The town is named for the Gelderland province in the Netherlands. The town of Guilderland is on the central-northwest border of the county. It is just west of Albany, the capital of the U.S. state of New York.

Watervliet is a city in northeastern Albany County, New York, United States. The population was 10,375 as of the 2020 census. Watervliet is north of Albany, the capital of the state, and is bordered on the north, west, and south by the town of Colonie. The city is also known as "the Arsenal City".

Glenmont is a hamlet in the town of Bethlehem, Albany County, New York, United States. Glenmont is in the northeastern corner of the town and is a suburb of the neighboring city of Albany. It is bordered to the east by the Hudson River. Originally a farm town, today Glenmont is home to residential neighborhoods, a busy commercial corridor along Route 9W, and industry along the riverfront. It is part of the Bethlehem Central School District, Glenmont contains Glenmont Elementary School, an elementary school for grades K-5, the current principal is Laura Heffernan.

New York State Route 85 (NY 85) is a state highway in Albany County, New York, in the United States. It is 26.49 miles (42.63 km) in length and runs from CR 353 in Rensselaerville to Interstate 90 (I-90) exit 4 in Albany. It also has a loop route, NY 85A, which connects NY 85 to the village of Voorheesville. The portion of NY 85 north of NY 140 to the Bethlehem–Albany town/city line is known as the Slingerlands Bypass. From there north to I-90, the road is a four-lane freeway named the Crosstown Arterial.

New York State Route 443 (NY 443) is an east–west state highway in the Capital District of New York in the United States. The route begins at an intersection with NY 30 in the town of Schoharie and ends 33.44 miles (53.82 km) later at a junction with U.S. Route 9W (US 9W) and US 20 in the city of Albany. It ascends the Helderberg Escarpment in the towns of Berne and New Scotland. Within the town of Bethlehem and the city of Albany, NY 443 is known as Delaware Avenue.

Slingerlands is a hamlet in the town of Bethlehem, Albany County, New York, United States. It is located immediately west of Delmar and near the New Scotland town-line and south of the Albany city-limits, and is thus a suburb of Albany. The Slingerlands ZIP Code (12159) includes parts of the towns of New Scotland and Guilderland.

Elsmere is a hamlet of the town of the Bethlehem in Albany County, New York, United States. The hamlet is a suburb of the neighboring city of Albany. From the northeast to the southwest, it is bisected by New York Route 443, which is also the hamlet's main street and a major commuter route into Albany. Delaware Avenue is also home to most of the office and retail locations in Elsmere, including the largest such location: Delaware Plaza.

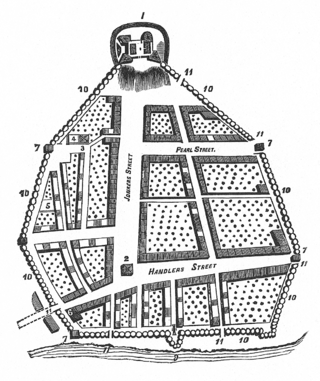

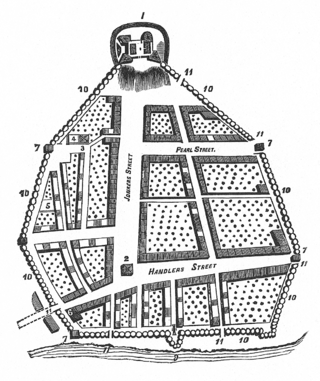

Fort Nassau was the first Dutch settlement in North America, located beside the "North River" within present-day Albany, New York, in the United States. The factorij was a small fortification which served as a trading post and warehouse.

New York State Route 140 (NY 140) is an east–west state highway located entirely within the town of Bethlehem in Albany County, New York, in the United States. The highway runs for 2.07 miles (3.33 km) from a roundabout with NY 85 near the hamlet of Slingerlands to an intersection with NY 443 in the hamlet of Delmar. The first mile (1.6 km) of the route is a four-lane divided highway named Cherry Avenue Extension, while the second mile follows a two-lane street known as Kenwood Avenue. NY 140 initially followed Kenwood Avenue from the center of Slingerlands to Delmar when it was assigned in the mid-1930s; however, the route was altered to bypass Slingerlands in the mid-1970s.

Feura Bush is a hamlet in the town of New Scotland, Albany County, New York, United States. It is in the southeastern corner of the town, along the Bethlehem town-line, eight miles south of Albany. The Feura Bush ZIP Code (12067) includes parts of the town of Bethlehem. It is in the Onesquethaw Volunteer Fire Company fire protection district. The 2020 Census showed 28 employer establishments in the hamlet.

The streets of Albany, New York, have had a long history going back almost 400 years. Many of the streets have changed names over the course of time, some have changed names many times. Some streets no longer exist, others have changed course. Some roads existed only on paper. The oldest streets were haphazardly laid out with no overall plan until Simeon De Witt's 1794 street grid plan. The plan had two grids, one west of Eagle Street and the old stockade, and another for the Pastures District south of the old stockade.

Lisha Kill is a hamlet in the town of Colonie, Albany County, New York, United States. Lisha Kill lies on New York Route 5 in the western section of the town. The hamlet received its name from the creek of the same name, Lisha Kill, kill being Dutch for creek or stream. The stream is also referred to as Lisha's Kill and received its name from a local legend about a Native American woman who is buried along its banks.

Kenwood was a hamlet in the Town of Bethlehem, New York. The hamlet spanned both sides of the Normans Kill near the area where the Normans Kill flows into the Hudson River. In 1870, and again in 1910, northern portions of Kenwood were annexed by the City of Albany, New York.

South Bethlehem is a hamlet in the town of Bethlehem, Albany County, New York, United States. The hamlet sits on New York State Route 396 and lies southwest of the Selkirk Rail Yard and just north of the Coeymans town line.

New Salem is a hamlet in the town of New Scotland, Albany County, New York, United States. It is located in a valley at the foot of the Helderberg Escarpment along New York State Route 85. A local fair and car show is held every year in this small hamlet. It is also home to the town of New Scotland's community center and museum.

Clarksville is a hamlet in the town of New Scotland, Albany County, New York, United States. It is situated along Delaware Turnpike in the southern part of the town at the foot of the Helderberg Escarpment. It is the site of the Clarksville Cave and has an annual Clarksville Heritage Day and Car Show. It is in the Onesquethaw Volunteer Fire Company fire protection district.

The Normans Kill is a 45.4-mile-long (73.1 km) creek in New York's Capital District located in Schenectady and Albany counties. It flows southeasterly from its source in the town of Duanesburg near Delanson to its mouth at the Hudson River in the town of Bethlehem. In the town of Guilderland, the stream is dammed to create the Watervliet Reservoir, a drinking water source for the city of Watervliet and the Town of Guilderland. A one megawatt hydrolectric plant at the dam provides power to pump water to the filtration plant.

The Whipple Cast and Wrought Iron Bowstring Truss Bridge, is located near the entrance to Stevens Farm in southwestern Albany, New York, United States. It was built in 1867, but not moved to its present location until 1899. It is one of the oldest surviving iron bridges in the county, one of the few that use both cast and wrought iron and one of only two surviving examples of the Whipple bowstring truss type. In 1971 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the only bridge in the city of Albany so far to be listed individually.