Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork, was a British architect and noble often called the "Apollo of the Arts" and the "Architect Earl". The son of the 2nd Earl of Burlington and 3rd Earl of Cork, Burlington never took more than a passing interest in politics despite his position as a Privy Counsellor and a member of both the British House of Lords and the Irish House of Lords. His great interests in life were architecture and landscaping, and he is remembered for being a builder and a patron of architects, craftsmen and landscapers, Indeed, he is credited with bringing Palladian architecture to Britain and Ireland. His major projects include Burlington House, Westminster School, Chiswick House and Northwick Park.

William Kent was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, but his real talent was for design in various media.

Stourhead is a 1,072-hectare (2,650-acre) estate at the source of the River Stour in the southwest of the English county of Wiltshire, extending into Somerset.

The Villa d'Este is a 16th-century villa in Tivoli, near Rome, famous for its terraced hillside Italian Renaissance garden and especially for its profusion of fountains. It is now an Italian state museum, and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

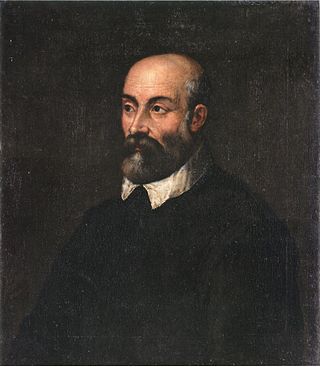

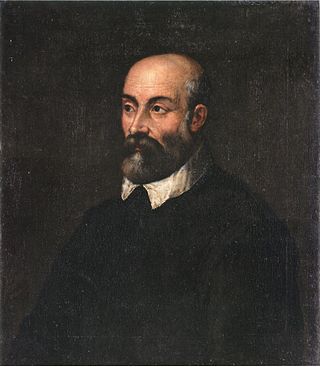

Andrea Palladio was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of the most influential individuals in the history of architecture. While he designed churches and palaces, he was best known for country houses and villas. His teachings, summarized in the architectural treatise, The Four Books of Architecture, gained him wide recognition.

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and the principles of formal classical architecture from ancient Greek and Roman traditions. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Palladio's interpretation of this classical architecture developed into the style known as Palladianism.

West Wycombe Park is a country house built between 1740 and 1800 near the village of West Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England. It was conceived as a pleasure palace for the 18th-century libertine and dilettante Sir Francis Dashwood, 2nd Baronet. The house is a long rectangle with four façades that are columned and pedimented, three theatrically so. The house encapsulates the entire progression of British 18th-century architecture from early idiosyncratic Palladian to the Neoclassical, although anomalies in its design make it architecturally unique. The mansion is set within an 18th-century landscaped park containing many small temples and follies, which act as satellites to the greater temple, the house.

Giacomo Leoni, also known as James Leoni, was an Italian architect, born in Venice. He was a devotee of the work of Florentine Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, who had also been an inspiration for Andrea Palladio. Leoni thus served as a prominent exponent of Palladianism in English architecture, beginning in earnest around 1720. Also loosely referred to as Georgian, this style is rooted in Italian Renaissance architecture.

Palazzo del Te, or simply Palazzo Te, is a palace in the suburbs of Mantua, Italy. It is an example of the mannerist style of architecture, and the acknowledged masterpiece of Giulio Romano.

The Villa Giulia is a villa in Rome, Italy. It is named after Pope Julius III, who had it built in 1551–1553 on what was then the edge of the city. Today it is publicly owned, and houses the Museo Nazionale Etrusco, a collection of Etruscan art and artifacts.

The Villa Farnese, also known as Villa Caprarola, is a pentagonal mansion in the town of Caprarola in the province of Viterbo, Northern Lazio, Italy, approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi) north-west of Rome, originally commissioned and owned by the House of Farnese. A property of the Republic of Italy, Villa Farnese is run by the Polo Museale del Lazio. This villa is not to be confused with two similarly-named properties of the family, the Palazzo Farnese and the Villa Farnesina, both in Rome.

Marble Hill House is a Neo-Palladian villa, now Grade I listed, in Twickenham in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It was built between 1724 and 1729 as the home of Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk, who lived there until her death. The compact design soon became famous and furnished a standard model for the Georgian English villa and for plantation houses in the American colonies.

Colen Campbell was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer who played an important part in the development of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectural designs, he is known for Vitruvius Britannicus, three volumes of high-quality engravings showing the great houses of the time.

The Villa Farnesina is a Renaissance suburban villa in the Via della Lungara, in the district of Trastevere in Rome, central Italy. Built between 1506 and 1510 for Agostino Chigi, the Pope's wealthy Sienese banker, it was a novel type of suburban villa, subsidiary to his main Palazzo Chigi in the city. It is especially famous for the rich frescos by Raphael and other High Renaissance artists that remain in situ.

Villa Borghese Pinciana is a villa built by the architect Flaminio Ponzio, developing sketches by Scipione Borghese.

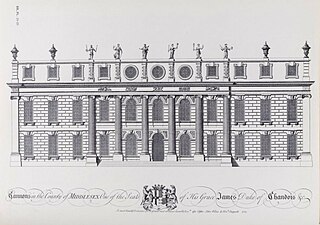

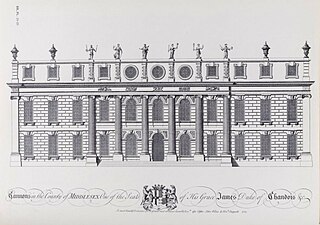

Cannons was a stately home in Little Stanmore, Middlesex, England. It was built by James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, between 1713 and 1724 at a cost of £200,000, replacing an earlier house on the site. Chandos' house was razed in 1747 and its contents dispersed.

Scott's Grotto in Ware, Hertfordshire, is a Grade I listed building and with six chambers the most extensive shell grotto in the United Kingdom. "It is, although on a small scale, far more complex than Alexander Pope's at Twickenham. Compared with the grotto at Stourhead, on the other hand, it is minute, but that only enhances the enchantment." The surrounding gardens and structures are Grade II* listed.

The Mawson Arms/Fox and Hounds is a Grade II* listed public house at 110 Chiswick Lane South. It is at the end of a terrace of five listed houses named Mawson Row in Old Chiswick. This was built in about 1715 for Thomas Mawson, the owner of what became Fuller's Griffin Brewery, which they adjoin.

Pieter Andreas Rijsbrack was a Flemish painter of still lifes and landscapes who was active in England in the first half of the 18th century. He is particularly known for launching the vogue of topographical views of English country houses and gardens. He was the older brother of the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack.

Twickenham War Memorial, in Radnor Gardens, Twickenham, London, commemorates the men of the district of Twickenham who died in the First World War. After 1945, the memorial was updated to recognise casualties from the Second World War. The memorial was commissioned by Twickenham Urban District Council in 1921. It was designed by the sculptor Mortimer Brown, and is Brown's only significant public work. The memorial is unusual for its representation of a jubilant soldier returning home. It became a Grade II* listed structure in 2017.