Thomas Newcomen was an English inventor who created the atmospheric engine, the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. He was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling.

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creating a partial vacuum which allowed the atmospheric pressure to push the piston into the cylinder. It was historically significant as the first practical device to harness steam to produce mechanical work. Newcomen engines were used throughout Britain and Europe, principally to pump water out of mines. Hundreds were constructed throughout the 18th century.

The Watt steam engine design became synonymous with steam engines, and it was many years before significantly new designs began to replace the basic Watt design.

John "Iron-Mad" Wilkinson was an English industrialist who pioneered the manufacture of cast iron and the use of cast-iron goods during the Industrial Revolution. He was the inventor of a precision boring machine that could bore cast iron cylinders, such as cannon barrels and piston cylinders used in the steam engines of James Watt. His boring machine has been called the first machine tool. He also developed a blowing device for blast furnaces that allowed higher temperatures, increasing their efficiency, and helped sponsor the first iron bridge in Coalbrookdale. He is notable for his method of cannon boring, his techniques at casting iron and his work with the government of France to establish a cannon foundry.

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

Blists Hill Victorian Town is an open-air museum built on a former industrial complex located in the Madeley area of Telford, Shropshire, England. The museum attempts to recreate the sights, sounds and smells of a Victorian Shropshire town in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is one of ten museums operated by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

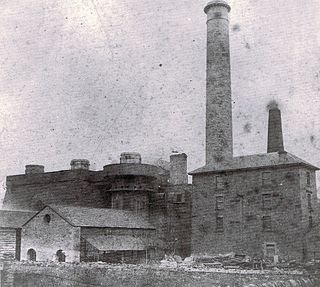

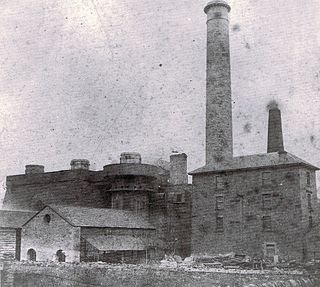

The Madeley Wood Company was formed in 1756 when the Madeley Wood Furnaces, also called Bedlam Furnaces, were built beside the River Severn, one mile west of Blists Hill.

Abraham Darby III was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Abraham Darby, in his later life called Abraham Darby the Elder, now sometimes known for convenience as Abraham Darby I, was a British ironmaster and foundryman. Born into an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution, Darby developed a method of producing pig iron in a blast furnace fuelled by coke rather than charcoal. This was a major step forward in the production of iron as a raw material for the Industrial Revolution.

Horsehay is a suburban village on the western outskirts of Dawley, which, along with several other towns and villages, now forms part of the new town of Telford in Shropshire, England. Horsehay lies in the Dawley Hamlets parish, and on the northern edge of the Ironbridge Gorge area.

The Shropshire Canal was a tub boat canal built to supply coal, ore and limestone to the industrial region of east Shropshire, England, that adjoined the River Severn at Coalbrookdale. It ran from a junction with the Donnington Wood Canal ascending the 316 yard long Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane to its summit level, it made a junction with the older Ketley Canal and at Southall Bank the Coalbrookdale (Horsehay) branch went to Brierly Hill above Coalbrookdale; the main line descended via the 600 yard long Windmill Incline and the 350 yard long Hay Inclined Plane to Coalport on the River Severn. The short section of the Shropshire Canal from the base of the Hay Inclined Plane to its junction with the River Severn is sometimes referred to as the Coalport Canal.

Shadrach Fox was the ironmaster who preceded Abraham Darby at Coalbrookdale.

A blowing engine is a large stationary steam engine or internal combustion engine directly coupled to air pumping cylinders. They deliver a very large quantity of air at a pressure lower than an air compressor, but greater than a centrifugal fan.

Parkend Ironworks, also known as Parkend Furnace, in the village of Parkend, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England, was a coke-fired furnace built in 1799. Most of the works were demolished between 1890 and 1908, but the engine house survived and is arguably the best preserved example of its kind to be found in the United Kingdom.

A water-returning engine was an early form of stationary steam engine, developed at the start of the Industrial Revolution in the middle of the 18th century. The first beam engines did not generate power by rotating a shaft but were developed as water pumps, mostly for draining mines. By coupling this pump with a water wheel, they could be used to drive machinery.

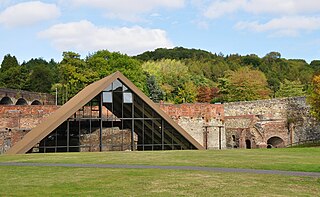

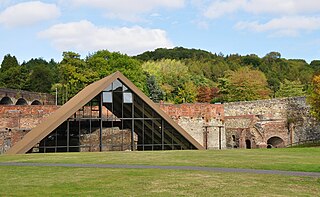

The Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron is one of ten Ironbridge Gorge Museums administered by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. The museum is based in the village of Coalbrookdale in the Ironbridge Gorge, in Shropshire, England, within a World Heritage Site, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.

The Darby Houses museum is one of ten Ironbridge Gorge Museums administered by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. It is based in the village of Coalbrookdale in the Ironbridge Gorge, in Shropshire, England within a World Heritage Site, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.

The Museum of the Gorge, originally the Severn Warehouse, is one of the ten museums of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. It portrays the history of the Ironbridge Gorge and the surrounding area of Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, England.

Richard Reynolds was an ironmaster, a partner in the ironworks in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, at a significant time in the history of iron production. He was a Quaker and philanthropist.

William Reynolds was an ironmaster and a partner in the ironworks in Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, England. He was interested in advances in science and industry, and invented the inclined plane for canals.