Related Research Articles

Incest is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity, and sometimes those related by lineage. It is forbidden and considered immoral in most societies, and can lead to an increased risk of genetic disorders in children in case of pregnancy.

East Asia generally encompasses the histories of China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Taiwan from prehistoric times to the present. Each of its countries has a different national history, but East Asian Studies scholars maintain that the region is also characterized by a distinct pattern of historical development. This is evident in the relationships among traditional East Asian civilizations, which not only involve the sum total of historical patterns but also a specific set of patterns that has affected all or most of traditional East Asia in successive layers.

Chinese surnames are used by Han Chinese and Sinicized ethnic groups in Greater China, Korea, Vietnam and among overseas Chinese communities around the world such as Singapore and Malaysia. Written Chinese names begin with surnames, unlike the Western tradition in which surnames are written last. Around 2,000 Han Chinese surnames are currently in use, but the great proportion of Han Chinese people use only a relatively small number of these surnames; 19 surnames are used by around half of the Han Chinese people, while 100 surnames are used by around 87% of the population. A report in 2019 gives the most common Chinese surnames as Wang and Li, each shared by over 100 million people in China. The remaining eight of the top ten most common Chinese surnames are Zhang, Liu, Chen, Yang, Huang, Zhao, Wu and Zhou.

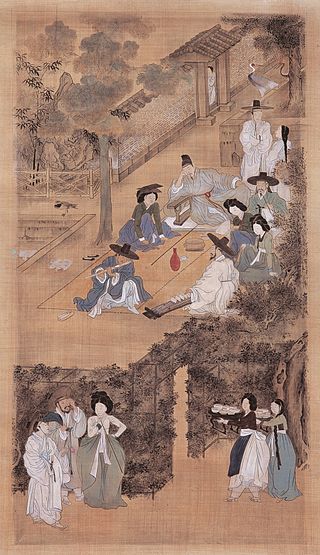

Korean Confucianism is the form of Confucianism that emerged and developed in Korea. One of the most substantial influences in Korean intellectual history was the introduction of Confucian thought as part of the cultural influence from China.

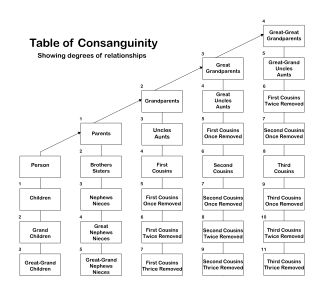

Consanguinity is the characteristic of having a kinship with a relative who is descended from a common ancestor.

Throughout the ages, there have been various popular religious traditions practiced on the Korean peninsula. The oldest indigenous religion of Korea is the Korean folk religion, which has been passed down from prehistory to the present. Buddhism was introduced to Korea from China during the Three Kingdoms era in the fourth century, and the religion pervaded the culture until the Joseon Dynasty when Confucianism was established as the state philosophy. During the Late Joseon Dynasty, in the 19th century, Christianity began to gain a foothold in Korea. While both Christianity and Buddhism would play important roles in the resistance to the Japanese occupation of Korea in the first half of the 20th century, only about 4% of Koreans were members of a religious organization in 1940.

The Chinese kinship system is among the most complicated of all the world's kinship systems. It maintains a specific designation for almost every member's kin based on their generation, lineage, relative age, and gender. The traditional system was agnatic, based on patriarchal power, patrilocal residence, and descent through the male line. Although there has been much change in China over the last century, especially after 1949, there has also been substantial continuity.

Article 809 of the Korean Civil Code was the codification of a traditional rule prohibiting marriage between men and women who have the same surname resulting from belonging to the same clan and possessing the same genealogical patriline and sharing the same ancestral home (bon-gwan). On 16 July 1997, the Constitutional Court of Korea ruled the article unconstitutional. The National Assembly of South Korea passed an amendment to the Article in March 2002, which came into force on 31 March 2005, and prohibited marriage only between men and women who are closely related.

Marriage law is the legal requirements, an aspect of family law, that determine the validity of a marriage, and which vary considerably among countries in terms of what can and cannot be legally recognised by the state.

Marriage in Korea mirrors many of the practices and expectations of marriages in other societies. Modern practices are a combination of millennia-old traditions and global influences.

A cousin marriage is a marriage where the spouses are cousins. The practice was common in earlier times and continues to be common in some societies today, though in some jurisdictions such marriages are prohibited. Worldwide, more than 10% of marriages are between first or second cousins. Cousin marriage is an important topic in anthropology and alliance theory.

In law, a prohibited degree of kinship refers to a degree of consanguinity, or sometimes affinity between persons that makes sex or marriage between them illegal.

Hanpu, later Wanyan Hanpu, was a leader of the Jurchen Wanyan clan in the early tenth century. According to the ancestral story of the Wanyan clan, Hanpu came from Goryeo when he was sixty years old, reformed Jurchen customary law, and then married a sixty-year-old local woman who bore him three children. His descendants eventually united Jurchen tribes into a federation and established the Jin dynasty in 1115. Hanpu was retrospectively given the temple name Shizu (始祖) and the posthumous name Emperor Yixian Jingyuan (懿憲景元皇帝) by the Jin dynasty.

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Republic of China (Taiwan) are regarded as some of the most comprehensive of those in Asia. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal, and same-sex marriage was legalized on 24 May 2019, following a Constitutional Court ruling in May 2017. Same-sex couples are able to jointly adopt children since 2023. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender characteristics in education has been banned nationwide since 2004. With regard to employment, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has also been prohibited by law since 2007.

Armenia does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions. The legal status of foreign same-sex marriages is unclear. On 3 July 2017, the Ministry of Justice reportedly stated that all marriages performed abroad are valid in Armenia, including marriages between people of the same sex. Article 143 of the Armenian Family Code states that Armenia recognizes foreign marriages as long as they conform with the legality of the territory where they were performed and contains no explicit prohibition of same-sex marriages. On the other hand, article 152 restricts the application of foreign law incompatible with the domestic public order. As of 2023, no instances of foreign same-sex marriage registrations are known. In 2019, Minister of Justice Rustam Badasyan said that the government does not recognize same-sex marriages.

Marriage in China has undergone change during the country's economic reform period, especially as a result of new legal policies such as the New Marriage Law of 1950 and the family planning policy in place from 1979 to 2015. The major transformation in the twentieth century is characterized by the change from traditional structures for Chinese marriage, such as arranged marriage, to one where the freedom to choose one’s partner is generally respected. However, both parental and cultural pressures are still placed on many individuals, especially women, to choose socially and economically advantageous marriage partners. In 2023, China had 7.68 million marriages. While divorce remains rare in China, the 1.96 million couples applying for divorce in 2010 represented a rate 14% higher than the year before and doubled from ten years ago. Despite this rising divorce rate, marriage is still thought of as a natural part of the life course and as a responsibility of good citizenship in China.

Sexuality in South Korea has been influenced by culture, religion, and westernization. Viewpoints in contemporary society can be viewed as a conflict between the traditional, conservative older generation and the more liberal and 'modern' generation. Due to this conflict, several issues in Korea, including sexual education, homosexuality, and sexual behavior are highly contested.

The history of Sino-Korean relations dates back to prehistoric times.

Society in the Joseon dynasty was built upon Neo-Confucianist ideals, namely the three fundamental principles and five moral disciplines. There were four classes: the yangban nobility, the "middle class" jungin, sangmin, or the commoners, and the cheonmin, the outcasts at the very bottom. Society was ruled by the yangban, who constituted 10% of the population and had several privileges. Slaves were of the lowest standing.

Sacrifice to Heaven is an Asian religious practice originating in the worship of Shangdi in China. In Ancient Chinese society, nobles of all levels constructed altars for Heaven. At first, only nobles could worship Shangdi but later beliefs changed and everyone could worship Shangdi.

References

- ↑ 牟潤孫 (1990). 海遺雜著 (in Chinese). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-962-201-407-7.

- 1 2 Ip, King Tak (2014). 儒家家庭價值的應用與生物科技倫理. International Journal of Chinese & Comparative Philosophy of Medicine (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). 12 (1): 21–37. doi: 10.24112/ijccpm.121554 . Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- 1 2 柳立言, ed. (2008-10-20). 中國史新論:法律史分冊 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 聯經出版事業公司. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-957-08-3328-7.

- ↑ Croll, Elisabeth (1981-02-12). The Politics of Marriage in Contemporary China. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-521-23345-3.

- ↑ Same-Surname-Same-Origin Marriage Ban case (95Hun-Ka6 on Article 809 (1) of the Civil Act);

^ THE FIRST TEN YEARS OF THE KOREAN CONSTITUTIONAL COURT (PDF), Constitutional Court of Korea, p. 242 (p.256 of the PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-19. - ↑ 管婺媛. "真愛無禁忌 同姓結婚17萬對". China Times (in Chinese). Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ↑ 法理学, 法史学 (in Chinese (China)). 中国人民大学书报资料中心. 2003. p. 71.

- ↑ ""Miễn là cùng họ" thì cả trăm đời vẫn không thể lấy nhau" (in Vietnamese). March 12, 2018.