Probainognathus meaning “progressive jaw” is an extinct genus of cynodonts that lived around 235 to 221.5 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Together with the genus Bonacynodon from Brazil, Probainognathus forms the family Probainognathidae. Probainognathus was a relatively small, carnivorous or insectivorous cynodont. Like all cynodonts, it was a relative of mammals, and it possessed several mammal-like features. Like some other cynodonts, Probainognathus had a double jaw joint, which not only included the quadrate and articular bones like in more basal synapsids, but also the squamosal and surangular bones. A joint between the dentary and squamosal bones, as seen in modern mammals, was however absent in Probainognathus.

Temnospondyli or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods — often considered primitive amphibians — that flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic periods, with fossils being found on every continent. A few species continued into the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous periods, but all had gone extinct by the Late Cretaceous. During about 210 million years of evolutionary history, they adapted to a wide range of habitats, including freshwater, terrestrial, and even coastal marine environments. Their life history is well understood, with fossils known from the larval stage, metamorphosis, and maturity. Most temnospondyls were semiaquatic, although some were almost fully terrestrial, returning to the water only to breed. These temnospondyls were some of the first vertebrates fully adapted to life on land. Although temnospondyls are amphibians, many had characteristics such as scales and armour-like bony plates that distinguish them from the modern soft-bodied lissamphibians.

Westlothiana is a genus of reptile-like tetrapod that lived about 338 million years ago during the latest part of the Viséan age of the Carboniferous. Members of the genus bore a superficial resemblance to modern-day lizards. The genus is known from a single species, Westlothiana lizziae. The type specimen was discovered in the East Kirkton Limestone at the East Kirkton Quarry, West Lothian, Scotland in 1984. This specimen was nicknamed "Lizzie the lizard" by fossil hunter Stan Wood, and this name was quickly adopted by other paleontologists and the press. When the specimen was formally named in 1990, it was given the specific name "lizziae" in homage to this nickname. However, despite its similar body shape, Westlothiana is not considered a true lizard. Westlothiana's anatomy contained a mixture of both "labyrinthodont" and reptilian features, and was originally regarded as the oldest known reptile or amniote. However, updated studies have shown that this identification is not entirely accurate. Instead of being one of the first amniotes, Westlothiana was rather a close relative of Amniota. As a result, most paleontologists since the original description place the genus within the group Reptiliomorpha, among other amniote relatives such as diadectomorphs and seymouriamorphs. Later analyses usually place the genus as the earliest diverging member of Lepospondyli, a collection of unusual tetrapods which may be close to amniotes or lissamphibians, or potentially both at the same time.

Ophiacodon is an extinct genus of synapsid belonging to the family Ophiacodontidae that lived from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian in North America and Europe. The genus was named along with its type species O. mirus by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878 and currently includes five other species. As an ophiacodontid, Ophiacodon is one of the most basal synapsids and is close to the evolutionary line leading to mammals.

Secodontosaurus is an extinct genus of "pelycosaur" synapsids that lived from between about 285 to 272 million years ago during the Early Permian. Like the well known Dimetrodon, Secodontosaurus is a carnivorous member of the Eupelycosauria family Sphenacodontidae and has a similar tall dorsal sail. However, its skull is long, low, and narrow, with slender jaws that have teeth that are very similar in size and shape—unlike the shorter, deep skull of Dimetrodon, which has large, prominent canine-like teeth in front and smaller slicing teeth further back in its jaws. Its unusual long, narrow jaws suggest that Secodontosaurus may have been specialized for catching fish or for hunting prey that lived or hid in burrows or crevices. Although no complete skeletons are currently known, Secodontosaurus likely ranged from about 2 to 2.7 metres (7–9 ft) in length, weighing up to 110 kilograms (250 lb).

Crassigyrinus is an extinct genus of carnivorous stem tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous Limestone Coal Group of Scotland and possibly Greer, West Virginia.

Eucritta is an extinct genus of stem-tetrapod from the Viséan epoch in the Carboniferous period of Scotland. The name of the type and only species, E. melanolimnetes is a homage to the 1954 horror film Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Mastodonsaurus is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian from the Middle Triassic of Europe. It belongs to a Triassic group of temnospondyls called Capitosauria, characterized by their large body size and presumably aquatic lifestyles. Mastodonsaurus remains one of the largest amphibians known, and may have exceeded 6 meters in length.

Colosteidae is a family of stegocephalians that lived in the Carboniferous period. They possessed a variety of characteristics from different tetrapod or stem-tetrapod groups, which made them historically difficult to classify. They are now considered to be part of a lineage intermediate between the earliest Devonian terrestrial vertebrates, and the different groups ancestral to all modern tetrapods, such as temnospondyls and reptiliomorphs.

Saharastega is an extinct genus of basal temnospondyl which lived during the Late Permian period, around 251 to 260 million years ago. Remains of Saharastega, discovered by paleontologist Christian Sidor at the Moradi Formation in Niger, were described briefly in 2005 and more comprehensively in 2006. The description is based on a skull lacking the lower jaws.

Loxomma is an extinct genus of Loxommatinae and one of the first Carboniferous tetrapods. They were first described in 1862 and further described in 1870 when two more craniums were found. It is mostly associated with the area of the United Kingdom. They share features with modern reptiles as well as with fish. They had 4 paddle-like limbs that they used to swim in lakes, but they breathed air. Their diet consisted mostly of live fish. They are of the family Baphetidae which are distinguished by their keyhole shaped orbits, while Loxomma themselves are distinguished by the unique texture on their skulls, said to be honeycomb-like.

Neopteroplax is an extinct genus of eogyrinid embolomere closely related to European genera such as Eogyrinus and Pteroplax. Members of this genus were among the largest embolomeres in North America. Neopteroplax is primarily known from a large skull found in Ohio, although fragmentary embolomere fossils from Texas and New Mexico have also been tentatively referred to the genus. Despite its similarities to specific European embolomeres, it can be distinguished from them due to a small number of skull and jaw features, most notably a lower surangular at the upper rear portion of the lower jaw.

Boii is an extinct genus of microsaur within the family Tuditanidae. It was found in Carboniferous coal from mines near the community of Kounov in the Czech Republic. The only remains of the genus consist of a crushed skull, shoulder girdle bones, and scales, which were similar to microsaurian elements originally referred to Asaphestera. Boii can be characterized by its heavily sculptured skull, thin ventral plate of the clavicles, and a larger number of fangs on the roof of the mouth. For many years the type and only known species, Boii crassidens, was considered to be a species of Sparodus, until 1966 when Robert Carroll assigned it to its own genus.

Odonterpeton is an extinct genus of "microsaur" from the Late Carboniferous of Ohio, containing the lone species Odonterpeton triangulare. It is known from a single partial skeleton preserving the skull, forelimbs, and the front part of the torso. The specimen was found in the abandoned Diamond Coal Mine of Linton, Ohio, a fossiliferous coal deposit dated to the late Moscovian stage, about 310 million years ago.

Kyrinion is an extinct genus of baphetid tetrapod from the Late Carboniferous of England. It is known from a skull that was found in Tyne and Wear county dating back to the Westphalian stage. Along with the skull is part of the lower jaw, an arch of the atlas bone and a rib possibly belonging to a cervical (neck) vertebra. The type species K. martilli was named from this material in 2003.

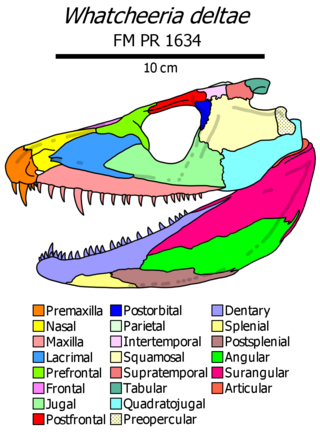

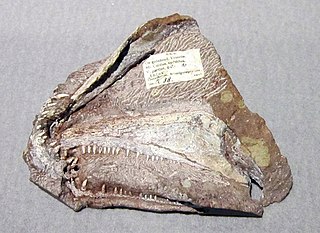

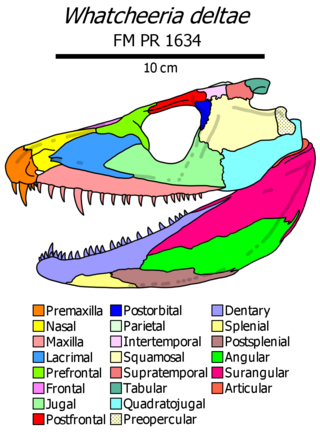

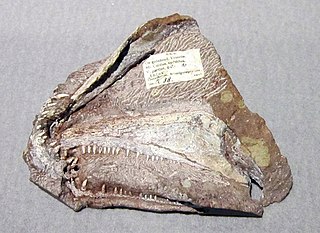

Whatcheeria is an extinct genus of early tetrapod from the Mississippian of Iowa. Fossils have been found in 340 million year old fissure fill deposits in the town of Delta. The type species, Whatcheeria deltae was named in 1995. It is classified within the family Whatcheeriidae, along with the closely related Pederpes and possibly Ossinodus.

Ymeria is an extinct genus of early stem tetrapod from the Devonian of Greenland. Of the two other genera of stem tetrapods from Greenland, Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, Ymeria is most closely related to Ichthyostega, though the single known specimen is smaller, the skull about 10 cm in length. A single interclavicle resembles that of Ichthyostega, an indication Ymeria may have resembled this genus in the post-cranial skeleton.

Sigournea is a genus of stem tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous. The genus contains only one species, the type species Sigournea multidentata, which was named in 2006 by paleontologists John R. Bolt and R. Eric Lombard on the basis of a single lower jaw from Iowa. The jaw came from a fissure-fill deposit of the St. Louis Limestone that was exposed in a quarry near the town of Sigourney and dates to the Viséan stage, making it approximately 335 million years old. Bolt and Lombard named the genus after Sigourney. The species name multidentata alludes to the many teeth preserved in the jaw. The jaw, which is housed in the Field Museum and cataloged as FM PR 1820, curves strongly downward but was probably straight to begin with, having been deformed by the process of fossilization after the individual died. Rooted in the dentary bone along the outermost edge of the jaw are 88 small, pointed marginal teeth. An additional row of even smaller teeth runs along the coronoids, three bones positioned lengthwise along the lower boundary of the dentary on the inner surface of the lower jaw. Bolt and Lombard were able to classify Sigournea as an early member of Tetrapoda based on the presence of bone surfaces covered in pits and ridges, a single row of dentary teeth, a jaw joint that faces upward, and an open groove for a lateral line along the outer surface of the jaw, and on the absence of teeth on the prearticular bone or enlarged fangs on the coronoids. Sigournea differs from other stem tetrapods in having several holes within a depression called the exomeckelian fenestra on the inner surface of the jaw.

Occidens is an extinct genus of stem tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous (Tournaisian) Altagoan Formation of Northern Ireland. It is known from a single type species, Occidens portlocki, named in 2004 on the basis of a left lower jaw described by British geologist Joseph Ellison Portlock in 1843.

Gordodon is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Early Permian of what is now Otero County, New Mexico. It was a member of the herbivorous sail-backed family Edaphosauridae and contains only a single species, the type species G. kraineri. Gordodon is unusual among early synapsids for its teeth, which were arranged similarly to those of modern mammals and unlike the simple, uniform lizard-like teeth of other early herbivorous synapsids. Gordodon had large incisor-like teeth at the front, followed by a prominent gap between them and a short row of peg-like teeth at the back. Gordodon was also relatively long-necked for an early synapsid, with elongated and gracile vertebrae in its neck and back. Like other edaphosaurids, Gordodon had a tall sail on its back made from the bony neural spines of its vertebrae. The spines also had bony knobs on them, a common trait of edaphosaurids, but the knobs of Gordodon are also unique for being more slender, thorn-like and randomly arranged along the spines. It is estimated to have been rather small at 1 m in length excluding the tail and 34 kg (75 lb) in weight.