Lifestyle and locomotion

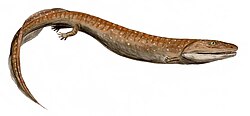

Whatcheeria was likely primarily aquatic: the poorly-ossified ankle and wrist are ill-suited for locomotion on land, as are the simple, blocky phalanges. This is supported further by the presence of lateral line canals on the skull. Regardless, the limbs are very large and strongly-built, with the shape of the humerus and ulna emphasizing retraction (swinging the forearms back to the torso) over any other direction of movement. Walking would have required strong lateral flexion (sideways bending) of the spine to allow the arms enough freedom of movement. Regardless, Whatcheeria was probably capable of significant lateral flexion due to its unspecialized posterior torso, similar to other early tetrapods. When swimming, Whatcheeria likely used its protruding limbs and paddle-like hands more than its short body or tail. A modern analogue may be the duckbilled platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), a mammal which swims at low speed but high maneuverability via a paddling motion of the forelimbs. In life, Whatcheeria potentially hunted by walking along lakebeds or wading through shallow water, using its relatively flexible neck to augment its ability to capture prey. [2] University of Chicago paleobiologists have likened its estimated lifestyle to modern freshwater predatory reptiles such as crocodilians and the alligator snapping turtle. [8]

Feeding strategy

The unusually narrow skull of Whatcheeria was strongly reinforced by complex modes of contact between its constituent bones, similar to the Devonian tetrapod Acanthostega . The rear of the skull was replete with interdigitating sutures between the bones of the skull roof and cheek, which would have diluted forces of compression between the sides and top of the rear skull. The snout was supplied with various front-to-back overlapping scarf joints, which would have resisted torsion (twisting) from struggling prey. Whatcheeria emphasizes these traits even further than Acanthostega, combining interdigitation and scarf joints at the front of the palate, the tip of the snout, and throughout the lower jaw. This may correspond to greater strength (and thus more reinforcement) at the front of the jaw when attacking prey, a notion supported by larger anterior fangs in Whatcheeria than other early tetrapods. There are no adaptations for cranial kinesis or suction feeding in Whatcheeria; as a whole, its skull was a stable and strong platform for biting, with an emphasis on the front of the snout for initial prey capture. [3]

Growth and development

Fossils of Whatcheeria represent a range of body sizes and ontogenetic stages, allowing it to decipher growth patterns in early tetrapods. Nine femora (thigh bones) from four size classes have been sampled for histological analyses, cutting a cross section through each bone to determine its developmental history. In larger femora, the cortex (hard outer bone layer) becomes proportionally thinner relative to the smallest femora, where the cortex makes up more than half of the bone's volume. [9]

Size-related variation also shows up in the type of bone deposited in each femur. The smallest femora (size classes one and two, late juveniles to subadults) have a mixture of fibrolamellar bone (a fast-developing composite material combining random bone fibers and concreted osteons) and parallel-fibered bone (fibrous layers woven together at a medium rate along the inner cortex). The largest femora (size classes three and four, adults) lose their fibrolamellar bone and gain lamellar bone (dense, plate-like bone slowly deposited along the circumference of the outer cortex).

The presence of fibrolamellar bone is unique to Whatcheeria among early tetrapods, and is an indicator of fast juvenile development more similar to amniotes than most extinct or living amphibians. [9] This condition suggests previously unexpected variability in the development of early tetrapods, considering there is also some evidence for faster-than-expected growth in Eusthenopteron , a tetrapodomorph fish related to tetrapods. [8] The presence of parallel-fibered bone also indicate that the smallest known femora merely represent late juveniles, and that younger individuals, which likely developed even faster, have not been fossilized at the Delta locality. None of the femora have growth marks, meaning that growth was continuous year-round, and not interrupted by resource scarcity or adverse seasonality. A thin cortex may allow adult Whatcheeria to control their buoyancy more precisely, a useful adaptation for a large aquatic predator. Greererpeton , a colosteid from the same general time period, grew slower and less continuously, and retained a thick cortex well into adulthood. These developmental differences may be a consequence of niche differentiation. [9]