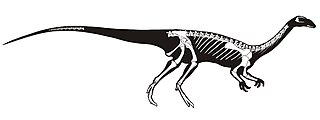

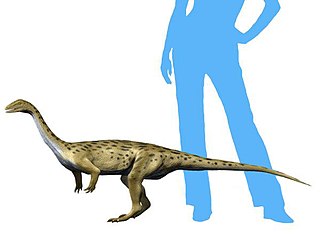

Eoraptor is a genus of small, lightly built, basal sauropodomorph dinosaur. One of the earliest-known dinosaurs and one of the earliest sauropodomorphs, it lived approximately 231 to 228 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in Western Gondwana, in the region that is now northwestern Argentina. The type and only species, Eoraptor lunensis, was first described in 1993, and is known from an almost complete and well-preserved skeleton and several fragmentary ones. Eoraptor had multiple tooth shapes, which suggests that it was omnivorous.

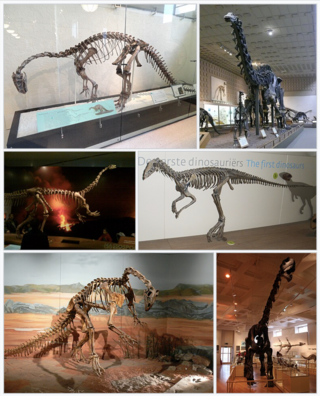

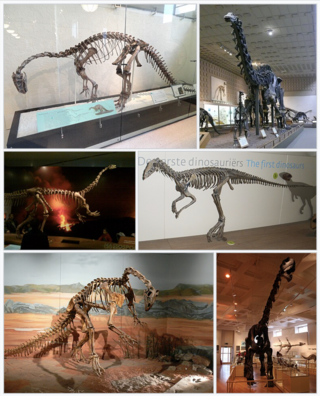

Sauropodomorpha is an extinct clade of long-necked, herbivorous, saurischian dinosaurs that includes the sauropods and their ancestral relatives. Sauropods generally grew to very large sizes, had long necks and tails, were quadrupedal, and became the largest animals to ever walk the Earth. The prosauropods, which preceded the sauropods, were smaller and were often able to walk on two legs. The sauropodomorphs were the dominant terrestrial herbivores throughout much of the Mesozoic Era, from their origins in the Late Triassic until their decline and extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

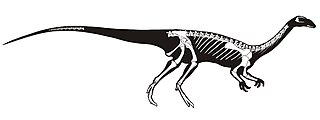

Saturnalia is an extinct genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur known from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. It contains one species, Saturnalia tupiniquim. It is one of the earliest known dinosaurs.

Herrerasauridae is a family of carnivorous dinosaurs, possibly basal to either theropods or even all of saurischians, or even their own branching from Dracohors, separate from Dinosauria altogether. They are among the oldest known dinosaurs, first appearing in the fossil record around 233.23 million years ago, before becoming extinct by the end of the Carnian stage. Herrerasaurids were relatively small-sized dinosaurs, normally no more than 4 metres (13 ft) long, although the holotype specimen of "Frenguellisaurus ischigualastensis" is thought to have reached around 6 meters long. The best known representatives of this group are from South America, where they were first discovered in the 1930s in relation to Staurikosaurus and 1960s in relation to Herrerasaurus. A nearly complete skeleton of Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis was discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation in San Juan, Argentina, in 1988. Less complete possible herrerasaurids have been found in North America and Africa, and they may have inhabited other continents as well.

Herrerasaurus is likely a genus of saurischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic period. Measuring 6 m (20 ft) long and weighing around 350 kg (770 lb), this genus was one of the earliest dinosaurs from the fossil record. Its name means "Herrera's lizard", after the rancher who discovered the first specimen in 1958 in South America. All known fossils of this carnivore have been discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation of Carnian age in northwestern Argentina. The type species, Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, was described by Osvaldo Reig in 1963 and is the only species assigned to the genus. Ischisaurus and Frenguellisaurus are synonyms.

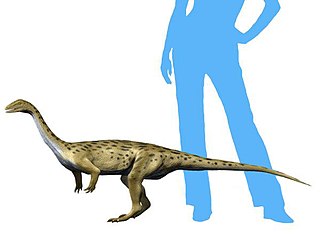

Guaibasaurus is an extinct genus of basal saurischian dinosaur known from the Late Triassic Caturrita Formation of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. Most analyses recover it as a sauropodomorph, although there are some suggestions that it was a theropod instead. In 2016 Gregory S. Paul estimated it at 2 meters and 10 kg, whereas in 2020 Molina-Pérez and Larramendi listed it at 3 meters and 35 kg.

Alwalkeria is a genus partly based on basal saurischian dinosaur remains from the Late Triassic, living in India.

Chindesaurus is an extinct genus of basal saurischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic of the southwestern United States. It is known from a single species, C. bryansmalli, based on a partial skeleton recovered from Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. The original specimen was nicknamed "Gertie", and generated much publicity for the park upon its discovery in 1984 and airlift out of the park in 1985. Other fragmentary referred specimens have been found in Late Triassic sediments throughout Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, but these may not belong to the genus. Chindesaurus was a bipedal carnivore, approximately as large as a wolf.

Dinosauromorpha is a clade of avemetatarsalians that includes the Dinosauria (dinosaurs) and some of their close relatives. It was originally defined to include dinosauriforms and lagerpetids, with later formulations specifically excluding pterosaurs from the group. Birds are the only dinosauromorphs which survive to the present day.

Saurosuchus is an extinct genus of large loricatan pseudosuchian archosaurs that lived in South America during the Late Triassic period. It was a heavy, ground-dwelling, quadrupedal carnivore, likely being the apex predator in the Ischigualasto Formation.

The Ischigualasto Formation is a Late Triassic geological formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin of southwestern La Rioja Province and northeastern San Juan Province in northwestern Argentina. The formation dates to the late Carnian and early Norian stages of the Late Triassic, according to radiometric dating of ash beds.

Panphagia is a genus of sauropodomorph dinosaur described in 2009. It lived around 231 million years ago, during the Carnian age of the Late Triassic period in what is now northwestern Argentina. Fossils of the genus were found in the La Peña Member of the Ischigualasto Formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin. The name Panphagia comes from the Greek words pan, meaning "all", and phagein, meaning "to eat", in reference to its inferred omnivorous diet. Panphagia is one of the earliest known dinosaurs, and is an important find which may mark the transition of diet in early sauropodomorph dinosaurs.

Tawa is a genus of possible basal theropod dinosaurs from the Late Triassic period. The fossil remains of Tawa hallae, the type and only species were found in the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, US. Its discovery alongside the relatives of Coelophysis and Herrerasaurus supports the hypothesis that the earliest dinosaurs arose in Gondwana during the early Late Triassic period in what is now South America, and radiated from there around the globe. The specific name honours Ruth Hall, founder of the Ghost Ranch Museum of Paleontology.

Saturnaliidae is a family of basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs found in Brazil, Argentina and possibly Zimbabwe. It is not to be confused with Saturnalidae, a family of radiolarian protists.

Sanjuansaurus is a genus of herrerasaurid dinosaur from the Late Triassic (Carnian) Ischigualasto Formation of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin in northwestern Argentina.

Eodromaeus is an extinct genus of probable basal theropod dinosaurs from the Late Triassic of Argentina. Like many other of the earliest-known dinosaurs, it hails from the Carnian-age Ischigualasto Formation, within the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin of northwestern Argentina. Upon its discovery, it was argued to be one of the oldest true theropods, supplanting its contemporary Eoraptor, which was reinterpreted as a basal sauropodomorph.

Daemonosaurus is an extinct genus of possible theropod dinosaur from the Late Triassic of New Mexico. The only known fossil is a skull and neck fragments from deposits of the latest Triassic Chinle Formation at Ghost Ranch. Daemonosaurus was an unusual dinosaur with a short skull and large, fang-like teeth. It lived alongside early neotheropods such as Coelophysis, which would have been among the most common dinosaurs by the end of the Triassic. However, Daemonosaurus retains several plesiomorphic ("primitive") traits of the snout, and it likely lies outside the clade Neotheropoda. It may be considered a late-surviving basal theropod or non-theropod basal saurischian, possibly allied to other early predatory dinosaurs such as herrerasaurids or Tawa.

Buriolestes is a genus of early sauropodomorph dinosaurs from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation of the Paraná Basin in southern Brazil. It contains a single species, B. schultzi, named in 2016. The type specimen was found alongside a specimen of the lagerpetid dinosauromorph Ixalerpeton.

Nhandumirim is a genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Carnian age of Late Triassic Brazil. It is currently considered a saturnaliid sauropodomorph. The type and only species, Nhandumirim waldsangae, is known from a single immature specimen including vertebrae, a chevron, pelvic material, and a hindlimb found in the Santa Maria Formation in Rio Grande do Sul.

Gnathovorax is a genus of herrerasaurid saurischian dinosaur from the Santa Maria Formation in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. The type and only species is Gnathovorax cabreirai, described by Pacheco et al. in 2019.