Coelophysoidea is an extinct clade of theropod dinosaurs common during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a superficial similarity to the coelurosaurs, with which they were formerly classified, and some species had delicate cranial crests. Sizes range from about 1 to 6 m in length. It is unknown what kind of external covering coelophysoids had, and various artists have portrayed them as either scaly or feathered. Some species may have lived in packs, as inferred from sites where numerous individuals have been found together.

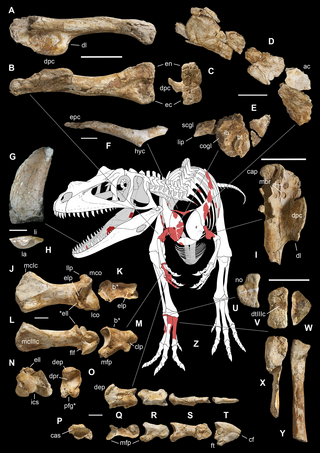

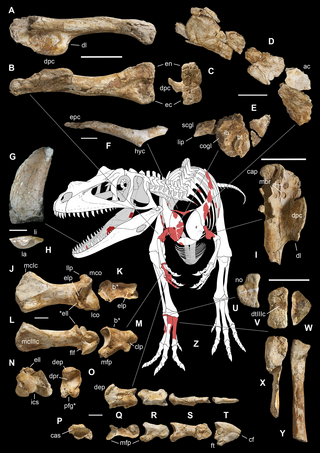

Saltriovenator is a genus of ceratosaurian dinosaur that lived during the Sinemurian stage of the Early Jurassic in what is now Italy. The type and only species is Saltriovenator zanellai; in the past, the species had been known under the informal name "saltriosaur". Although a full skeleton has not yet been discovered, Saltriovenator is thought to have been a large, bipedal carnivore similar to Ceratosaurus.

Coelurus is a genus of coelurosaurian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period. The name means "hollow tail", referring to its hollow tail vertebrae. Although its name is linked to one of the main divisions of theropods (Coelurosauria), it has historically been poorly understood, and sometimes confused with its better-known contemporary Ornitholestes. Like many dinosaurs studied in the early years of paleontology, it has had a confusing taxonomic history, with several species being named and later transferred to other genera or abandoned. Only one species is currently recognized as valid: the type species, C. fragilis, described by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1879. It is known from one partial skeleton found in the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, United States. It was a small bipedal carnivore with elongate legs.

Gojirasaurus is a genus of "coelophysoid" theropod dinosaur from the Late Triassic of New Mexico. It is named after the giant monster movie character Godzilla, and contains a single species, Gojirasaurus quayi.

Podokesaurus is a genus of coelophysoid dinosaur that lived in what is now the eastern United States during the Early Jurassic Period. The first fossil was discovered by the geologist Mignon Talbot near Mount Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1910. The specimen was fragmentary, preserving much of the body, limbs, and tail. In 1911, Talbot described and named the new genus and species Podokesaurus holyokensis based on it. The full name can be translated as "swift-footed lizard of Holyoke". This discovery made Talbot the first woman to find and describe a non-bird dinosaur. The holotype fossil was recognized as significant and was studied by other researchers, but was lost when the building it was kept in burned down in 1917; no unequivocal Podokesaurus specimens have since been discovered. It was made state dinosaur of Massachusetts in 2022.

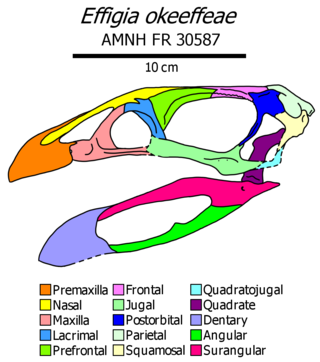

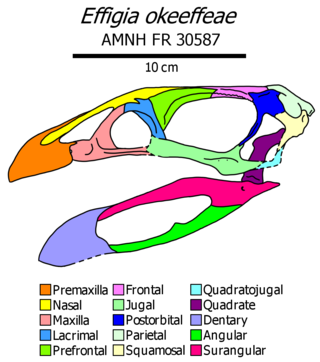

Effigia was an extinct genus of shuvosaurid known from the Late Triassic of New Mexico, south-western USA. With a bipedal stance, long neck, and a toothless beaked skull, Effigia and other shuvosaurids bore a resemblance to the ornithomimid dinosaurs of the Cretaceous Period. However, shuvosaurids were not dinosaurs, but were instead a specialized family of poposauroid pseudosuchians, meaning that their closest living relatives are crocodilians.

Zupaysaurus is an extinct genus of early theropod dinosaur living during the Norian stage of the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Fossils of the dinosaur were found in the Los Colorados Formation of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin in northwestern Argentina. Although a full skeleton has not yet been discovered, Zupaysaurus can be considered a bipedal predator, up to 4 metres (13 ft) long. It may have had two parallel crests running the length of its snout.

Camposaurus is a coelophysid dinosaur genus from the Norian stage of the Late Triassic period of North America. The pertinent fossil remains date back to the early to middle Norian stage, and is widely regarded as the oldest known neotheropod.

Aniksosaurus is a genus of avetheropod dinosaur from what is now Chubut Province, Argentina. It lived during the Cenomanian to Turonian of the Cretaceous period, between 96-91 million years ago. The type species, Aniksosaurus darwini, was formally described from the Bajo Barreal Formation of the Golfo San Jorge Basin by Rubén Dario Martínez and Fernando Emilio Novas in 2006; the name was first coined in 1995 and reported in the literature in 1997. The specific epithet honors Charles Darwin who visited Patagonia in 1832/1833 during the Voyage of the Beagle.

Chindesaurus is an extinct genus of basal saurischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic of the southwestern United States. It is known from a single species, C. bryansmalli, based on a partial skeleton recovered from Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. The original specimen was nicknamed "Gertie", and generated much publicity for the park upon its discovery in 1984 and airlift out of the park in 1985. Other fragmentary referred specimens have been found in Late Triassic sediments throughout Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, but these may not belong to the genus. Chindesaurus was a bipedal carnivore, approximately as large as a wolf.

Spinosuchus is an extinct genus of trilophosaurid allokotosaur from the Late Triassic of Texas, southern United States. It has been assigned to a variety of groups over its history, from coelophysid dinosaur to pseudosuchian to uncertain theropod dinosaur and to Proterosuchidae. This uncertainty is not unusual, given that it was only known from a poorly preserved, wall-mounted, partial vertebral column of an animal that lived in a time of diverse, poorly known reptile groups. However, newly collected material and recent phylogenetic studies of early archosauromorphs suggest that it represents an advanced trilophosaurid very closely related to Trilophosaurus.

Tawa is a genus of possible basal theropod dinosaurs from the Late Triassic period. The fossil remains of Tawa hallae, the type and only species were found in the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, US. Its discovery alongside the relatives of Coelophysis and Herrerasaurus supports the hypothesis that the earliest dinosaurs arose in Gondwana during the early Late Triassic period in what is now South America, and radiated from there around the globe. The specific name honours Ruth Hall, founder of the Ghost Ranch Museum of Paleontology.

Daemonosaurus is an extinct genus of possible theropod dinosaur from the Late Triassic of New Mexico. The only known fossil is a skull and neck fragments from deposits of the latest Triassic Chinle Formation at Ghost Ranch. Daemonosaurus was an unusual dinosaur with a short skull and large, fang-like teeth. It lived alongside early neotheropods such as Coelophysis, which would have been among the most common dinosaurs by the end of the Triassic. However, Daemonosaurus retains several plesiomorphic ("primitive") traits of the snout, and it likely lies outside the clade Neotheropoda. It may be considered a late-surviving basal theropod or non-theropod basal saurischian, possibly allied to other early predatory dinosaurs such as herrerasaurids or Tawa.

Megapnosaurus is an extinct genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 188 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Africa. The species was a small to medium-sized, lightly built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, that could grow up to 2.2 m (7.2 ft) long and weigh up to 13 kg (29 lb).

Coelophysis? kayentakatae is an extinct species of neotheropod dinosaur that lived approximately 200–196 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now the southwestern United States. It was originally named Syntarsus kayentakatae, but the genus Syntarsus was found to be preoccupied by a Colydiine beetle, so it was moved to the genus Megapnosaurus, and then to Coelophysis. A recent reassessment suggests that this species may require a new genus name.

The Rock Point Formation is a geologic formation in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. It preserves fossils dating back to the late Triassic.

Panguraptor is a genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur known from fossils discovered in Lower Jurassic rocks of southern China. The type and only known species is Panguraptor lufengensis. The generic name refers to the deity Pangu but also to the supercontinent Pangaea for which in a geological context the same characters are used: 盘古. Raptor means "seizer", "robber" in Latin. The specific name is a reference to the Lufeng Formation. The holotype specimen was recovered on 12 October 2007 from the Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, which is noted for sauropodomorph fossils. It was described in 2014 by You Hai-Lu and colleagues.

This timeline of coelophysoid research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the coelophysoids, a group of primitive theropod dinosaurs that were among Earth's dominant predators during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic epochs. Although formally trained scientists didn't discover coelophysoid fossils until the late 19th century, Native Americans of the modern southwestern United States may have already encountered their fossils. Navajo creation mythology describes the early Earth as being inhabited by a variety of different kinds of monsters who hunted humans for food. These monsters were killed by storms and the heroic Monster Slayers, leaving behind their bones. As these tales were told in New Mexico not far from bonebeds of Coelophysis, this dinosaur's remains may have been among the fossil remains that inspired the story.

Robert Joseph Gay is an American Paleontologist known for his work in the Chinle and Kayenta Formations in the southwest United States. He is known for the discovery of the first occurrence of Crosbysaurus from Utah, as well as his studies of cannibalism in Coelophysis and sexual dimorphism in Dilophosaurus. Since 2014, Gay has taken high school students to the Chinle of Comb Ridge, Utah, and he is currently making new discoveries there. In December 2017, he and coauthors Xavier A. Jenkins of Arizona State University and John R. Foster of the Museum of Moab formally published their study on the oldest known dinosaur from Utah, a neotheropod that is likely an animal similar to Coelophysis. Robert Gay is currently the Education Director at the Colorado Canyons Association.

The Chama Basin is a geologic structural basin located in northern New Mexico. The basin closely corresponds to the drainage basin of the Rio Chama and is located between the eastern margin of the San Juan Basin and the western margin of the Rio Grande Rift. Exposed in the basin is a thick and nearly level section of sedimentary rock of Permian to Cretaceous age, with some younger overlying volcanic rock. The basin has an area of about 3,144 square miles (8,140 km2).