Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, resulting in a more "standing" quadrupedal posture, as opposed to the lower sprawling posture of many reptiles and amphibians.

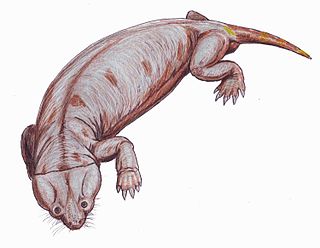

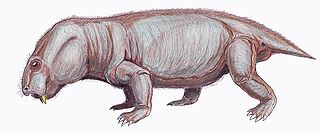

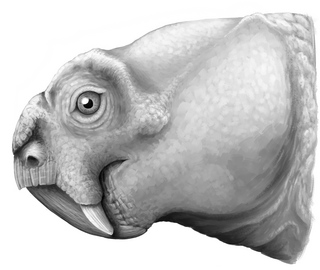

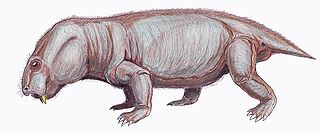

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivores that typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, typically toothless beak, unique amongst all synapsids. Dicynodonts first appeared in Southern Pangaea during the mid-Permian, ca. 270–260 million years ago, and became globally distributed and the dominant herbivorous animals in the Late Permian, ca. 260–252 Mya. They were devastated by the end-Permian Extinction that wiped out most other therapsids ca. 252 Mya. They rebounded during the Triassic but died out towards the end of that period. They were the most successful and diverse of the non-mammalian therapsids, with over 80-90 genera known, varying from rat-sized burrowers to elephant-sized browsers.

The Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone found in the Adelaide Subgroup of the Beaufort Group, a majorly fossiliferous and geologically important geological group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops located in the Teekloof Formation north-west of Beaufort West in the Western Cape, in the upper Middleton and lower Balfour Formations respectively from Colesberg of the Northern Cape to east of Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. The Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group, and is considered to be Late Permian in age.

The Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone found in the Adelaide Subgroup of the Beaufort Group, a majorly fossiliferous and geologically important Group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops located in the upper Teekloof Formation west of 24°E, the majority of the Balfour Formation east of 24°E, and the Normandien Formation in the north. It has numerous localities which are spread out from Colesberg in the Northern Cape, Graaff-Reniet to Mthatha in the Eastern Cape, and from Bloemfontein to Harrismith in the Free State. The Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group and is considered Late Permian (Lopingian) in age. Its contact with the overlying Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone marks the Permian-Triassic boundary.

The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone which correlates to the upper Adelaide and lower Tarkastad Subgroups of the Beaufort Group, a fossiliferous and geologically important geological Group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops in the south central Eastern Cape and in the southern and northeastern Free State. The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group, and is considered to be Early Triassic in age.

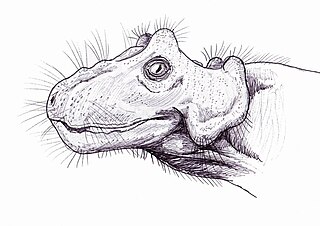

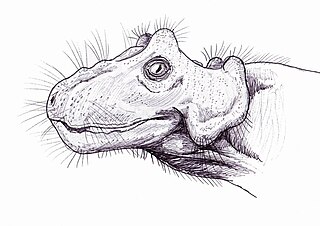

Moschorhinus is an extinct genus of therocephalian synapsid in the family Akidnognathidae with only one species: M. kitchingi, which has been found in the Late Permian to Early Triassic of the South African Karoo Supergroup. It was a large carnivorous therapsid, reaching 1.1–1.5 metres (3.6–4.9 ft) in total body length with the largest skull comparable to that of a lion in size, and had a broad, blunt snout which bore long, straight canines.

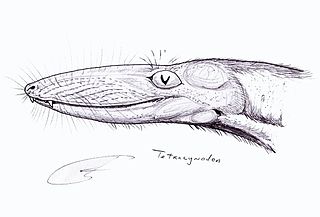

Tetracynodon is an extinct genus of therocephalian. Fossils of Tetracynodon have been found in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. Two species are known: the type species T. tenuis from the Late Permian and the species T. darti from the Early Triassic. Both species were small-bodied and probably fed on insects and small vertebrates. Although Tetracynodon is more closely related to mammals than to reptiles, its braincase is very primitive and more resembles that of modern amphibians and reptiles than of mammals.

Paraburnetia is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It is known for its species P. sneeubergensis and belongs to the family Burnetiidae. Paraburnetia lived just before the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event.

Myosaurus is a genus of dicynodont synapsids. Myosaurus was a small, herbivorous synapsid that existed around the early Triassic period. All of the fossils found of this species were found in Antarctica and South Africa. Compared to other fossils found from species that existed during this time, the Myosaurus is not common in the fossil record. This is due to a shortage of discovered fossils that possess characteristics unique to the Myosaurus. Notably, under 130 fossil fragments have been found that have been classified as Myosauridae, and almost all have been skulls. These skulls can be classified as Myosaurus because this species, unlike other dicynodonts, do not possess tusks or postfrontal teeth. The only species identified in the family Myosauridae is the Myosaurus gracilis, or M. gracilis. It should be recognized that the Myosaurus is almost always referred to as the M. gracilis in scientific research.

Broomistega is an extinct genus of temnospondyl in the family Rhinesuchidae. It is known from one species, Broomistega putterilli, which was renamed in 2000 from Lydekkerina putterilli Broom 1930. Fossils are known from the Early Triassic Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group in the Karoo Basin of present-day South Africa, a region that had been an enclave of Gondwana. Specimens of B. putterilli were once thought to represent young individuals of another larger rhinesuchid such as Uranocentrodon, but the species is now regarded as a paedomorphic taxon, possessing the features of juvenile rhinesuchids into adulthood.

Dicynodontoides is a genus of small to medium-bodied, herbivorous, emydopoid dicynodonts from the Late Permian. The name Dicynodontoides references its “dicynodont-like” appearance due to the caniniform tusks featured by most members of this infraorder. Kingoria, a junior synonym, has been used more widely in the literature than the more obscure Dicynodontoides, which is similar-sounding to another distantly related genus of dicynodont, Dicynodon. Two species are recognized: D. recurvidens from South Africa, and D. nowacki from Tanzania.

Progalesaurus is an extinct genus of galesaurid cynodont from the early Triassic. Progalesaurus is known from a single fossil of the species Progalesaurus lootsbergensis, found in the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Balfour Formation. Close relatives of Progalesaurus, other galesaurids, include Galesaurus and Cynosaurus. Galesaurids appeared just before the Permian-Triassic extinction event, and disappeared from the fossil record in the Middle-Triassic.

Platycraniellus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodonts from the Early Triassic. It is known from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Normandien Formation in South Africa. P. elegans is the only species in this genus based on the holotype specimen from the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History in Pretoria, South Africa. Due to limited fossil records for study, Platycraniellus has only been briefly described a handful of times.

Langbergia is an extinct genus of trirachodontid cynodont from the Early Triassic of South Africa. The type and only species L. modisei was named in 2006 after the farm where the holotype was found, Langberg 566. Langbergia was found in the Burgersdorp Formation in the Beaufort Group, a part of the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone. The closely related trirachodontids Trirachodon and Cricodon were found in the same area.

Manubrantlia was a genus of lapillopsid temnospondyls from the Early Triassic Panchet Formation of India. This genus is only known from a single holotype left jaw, given the designation ISI A 57. Despite the paucity of remains, the jaw is still identifiable as belonging to a relative of Lapillopsis. For example, all three of its coronoid bones possessed teeth, the articular bone is partially visible in lateral (outer) view, and its postsplenial does not contact the posterior meckelian foramen. However, the jaw also possesses certain unique features which justify the erection of a new genus separate from Lapillopsis. For example, the mandible is twice the size of any jaws referred to other lapillopsids. The most notable unique feature is an enlarged "pump-handle" shaped arcadian process at the back of the jaw. This structure is responsible for the generic name of this genus, as "Manubrantlia" translates from Latin to the English expression "pump-handle". The type and only known species of this genus is Manubrantlia khaki. The specific name refers to the greenish-brown mudstones of the Panchet Formation, with a color that had been described as "khaki" by the first British geologists who studied the formation.

The Balfour Formation is a geological formation that is found in the Beaufort Group, a major geological group that forms part of the greater Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. The Balfour Formation is the uppermost formation of the Adelaide Subgroup which contains all the Late Permian - Early Triassic aged biozones of the Beaufort Group. Outcrops and exposures of the Balfour Formation are found from east of 24 degrees in the highest mountainous escarpments between Beaufort West and Fraserburg, but most notably in the Winterberg and Sneeuberg mountain ranges near Cradock, the Baviaanskloof river valley, Graaff-Reniet and Nieu Bethesda in the Eastern Cape, and in the southern Free State province.

The Katberg Formation is a geological formation that is found in the Beaufort Group, a major geological group that forms part of the greater Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. The Katberg Formation is the lowermost geological formation of the Tarkastad Subgroup which contains the Lower to Middle Triassic-aged rocks of the Beaufort Group. Outcrops and exposures of the Katberg Formation are found east of 24 degrees onwards and north of Graaff-Reniet, Nieu Bethesda, Cradock, Fort Beaufort, Queensdown, and East London in the south, and ranges as far north as Harrismith in deposits that form a ring around the Drakensberg mountain ranges.

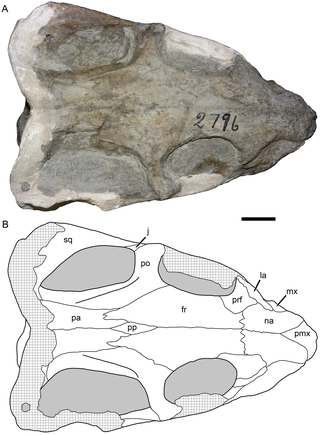

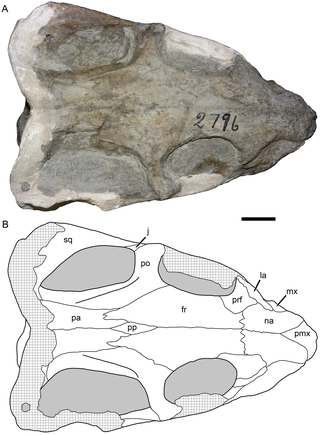

Thliptosaurus is an extinct genus of small kingoriid dicynodont from the latest Permian period of the Karoo Basin in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It contains the type and only known species T. imperforatus. Thliptosaurus is from the upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone, making it one of the youngest Permian dicynodonts known, living just prior to the Permian mass extinction. It also represents one of the few small bodied dicynodonts to exist at this time, when most other dicynodonts had large body sizes and many small dicynodonts had gone extinct. The unexpected discovery of Thliptosaurus in a region of the Karoo outside of the historically sampled localities suggests that it may have been part of an endemic local fauna not found in these historic sites. Such under-sampled localities may contain 'hidden diversities' of Permian faunas that are unknown from traditional samples. Thliptosaurus is also unusual for dicynodonts as it lacks a pineal foramen, suggesting that it played a much less important role in thermoregulation than it did for other dicynodonts.

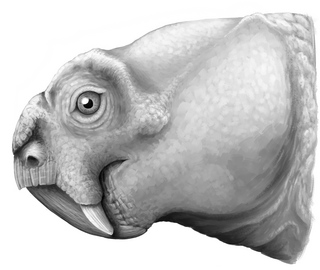

Counillonia is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsid from the area of Luang Prabang in Laos, Southeast Asia that lived at around the time of the Permian-Triassic boundary and possibly dates to the earliest Early Triassic. Its type and only known species is C. superoculis. Counillonia was related to the Triassic dicynodonts such as Lystrosaurus and the Kannemeyeriiformes that survived the Permian mass extinction, but it was more closely related to the Permian genus Dicynodon than to either of these lineages. Counillonia may then possibly represent another line of dicynodonts that survived the Permian mass extinction into the Triassic period, depending on its age. The discovery of Counillonia in Laos and its unexpected evolutionary relationships hint at the less well understood geographies of dicynodont diversity across the Permo-Triassic boundary outside of well explored regions like the Karoo Basin in South Africa.

Repelinosaurus is an extinct genus of dicynodont from the Purple Claystone Formation of Luang Prabang in Laos, Southeast Asia that lived at around the time of the Permian-Triassic boundary and possibly dates to the earliest Early Triassic. Its type and only known species is R. robustus. Repelinosaurus was originally described as the earliest known kannemeyeriiform dicynodont, supporting the idea of a more rapid radiation of the Triassic kannemeyeriiform dicynodonts during the Early Triassic following the Permian mass extinction. However, it may alternatively be more closely related to the Permian Dicynodon. The discovery of a potential early kannemeyeriiform in an understudied locality like Laos highlights the importance of such places in dicynodont research, which has been largely focused on historically important localities such as the Karoo Basin of South Africa.