Description

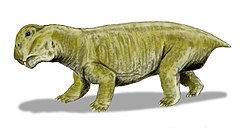

Taoheodon was a medium-sized dicynodont (basal skull length over 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long) currently only known from an incomplete skull and lower jaw. Based on the anatomy of other closely related dicynodonts such as Dicynodon, Taoheodon was probably a squat, sprawling quadruped with a short tail and a proportionally large head. Like other dicynodonts, Taoheodon was almost entirely toothless, sporting only a pair of tusks and a tortoise-like beak. [1] [2]

Skull

Like other dicynodonts, Taoheodon had a short skull with large temporal fenestra at the back, large orbits and a short snout, which in Taoheodon was proportionately short even for a dicynodont. Its skull is slightly longer than wide, with elongated temporal fenestra. The external nostril is rounded and not especially large for a dicynodont, but the area of bone behind and beneath it is hollowed out and concave compared to the rest of the snout. The nasal bones along the roof of the snout are relatively flat, but are nonetheless rugosely textured and bore a single weakly developed boss of tough skin or keratin on top of the snout. Likewise, the lacrimal and prefrontal bone form a distinct boss that bulges out to the side in front of each eye. By comparison, the postorbital bar behind the eyes is smooth and unornamented. The caniniform process housing the tusk is directed downwards from the snout, and sits entirely in front of the eyes. The pineal foramen (or "third eye") on the roof of the skull is large and positioned relatively far back. [1]

Lower jaw

The mandible of Taoheodon is mostly known from part of the dentary, with portions of the angular, surangular and splenial bones. The dentary is large and robust, with a rough, pitted surface texture at its front and along the top surface, corresponding to the horny beak typical of dicynodonts. The tip of the lower jaw is missing, so the exact shape of the beak is unknown; however, a low and wide curved ridge defines a clear edge between the side and front faces of the beak. Like other dicynodonts, the angular supports a prominent reflected lamina, which may have supported the eardrum in non-mammalian therapsids. In Taoheodon, the reflected lamina is large and rounded, facing down and back from the mandibular fenestra. [1] [3]

History of discovery

The holotype and only known specimen of Taoheodon, IVPP V 25335, was discovered in the valley of a tributary of the Tao He river, running through the lower part of the Sunjiagou Formation. The Sunjiagou Formation has been dated to the Late Permian (Lopingian epoch), although the exact age of the lower beds has been debated; either representing the late Wuchiapingian age or early Changhsingian. The lower Sunjiagou Formation is composed of grey to greenish-grey mudstones and fine grained sandstones, although the fossil of Taoheodon itself was found contained within an eroded rock nodule. This erosion resulted in the loss of the zygomatic arches and the tip of the snout from the specimen which had been exposed prior to collection, and the specimen has also been slightly compressed from top to bottom during fossilisation. The specimen was described in 2020 by Jun Liu as a new genus and species, Taoheodon baizhijuni. Taoheodon was named for the nearby Tao He river where it was discovered, combined with the Ancient Greek -odous for 'tooth', a common suffix in dicynodont generic names. The specific name is in honour of the fossil collector Bai Zhijun who discovered the specimen. [1] [4]

Classification

Taoheodon was a member of the dicynodont infraorder Dicynodontoidea, and is distinguished from all other dicynodonts by three unique autapomorphies: the top of postorbital bars behind the eyes have a shallow depression (fossa) where they meet the rest of the skull, the basisphenoid (a part on the underside of the braincase) slopes anterodorsally at a shallow angle in the basisphenoid-basioccipital tubera, and unlike other dicynodonts it lacks a keel on the pterygoid bones of the palate. Taoheodon was included in an updated phylogenetic analysis of dicynodonts using the combined datasets of Olivier et al. (2019) [5] and Kammerer (2019). [6] Within Dicynodontoidea, Taoheodon was found to group within a clade containing Dicynodon and very similar taxa that Liu identified as the "core-Dicynodon" clade.

The cladogram produced by Liu (2020), simplified and focused on the relationships of dicynodontoids, is shown below: [1]

The results of the analysis are almost identical to the cladograms produced from the previous studies, however, the position of the two Laotian dicynodonts Counillonia and Repelinosaurus differs from their original descriptions. The two Laotian genera were found to clade together with Taoheodon in the "core-Dicynodon" clade, contrasting with the analysis of Olivier and colleagues which originally found Repelinosaurus to be the basalmost kannemeyeriiform. Liu found Taoheodon and the Laotian dicynodonts to share a number of features, including notably short snouts, pineal foramens placed further back on the roof of the skull, anteriorly inclined occiputs, a fairly straight suture between the nasals and frontals, lacking the postfrontal bones, fairly flat postorbitals in the temporal area, and a large fossa on the ventral surface of the intertemporal bar. [1] [5]

Palaeobiogeography

The close relationship of Taoheodon to the Laotian dicynodonts suggests that there was a direct link between the North China Block, South China Block and Indochina Block that created a corridor of land for dicynodonts in Northern China to disperse into Laos on the Indochina Block and speciate. This paleobiogeographic inference has implications for the timing of the collisions between these landmasses, which although uncertainly dated, have typically been inferred to have occurred later during the Triassic period. The presence of a clade of closely related dicynodonts between these landmasses suggests that they were connected in some way by the end of the Permian. Furthermore, their position within a "core-Dicynodon" clade indicates that Taoheodon was part of a lineage of dicynodonts that could freely migrate from North China through Russia to South Africa. [1]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.