| "Dromasauria" Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

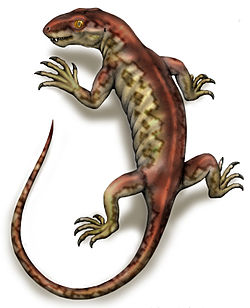

| Life restoration of Galechirus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | † Anomodontia |

| Informal group: | † Dromasauria Broom, 1907 |

| Included genera | |

| |

"Dromasaurs" are an artificial grouping of small anomodont therapsids from the Middle and Late Permian of South Africa. They represent either a paraphyletic grade or a polyphyletic grouping of small non-dicynodont basal anomodonts rather than a clade, and as such are considered an invalid group today. "Dromasaurs" were historically united by their superficially similar appearances that were unlike other known anomodonts. They are all small in size with slender limbs and long tails, and have short skulls with very large eye sockets. "Dromasauria" (sometimes also known as "Dromasauroidea") traditionally includes three genera, all from the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa: Galepus , Galechirus , and Galeops . These genera have sometimes been divided into two subgroups, the monotypic family Galeopidae (containing only Galeops) and the Galechiridae for Galechiris and Galepus. [1]

Despite their superficial similarities, "Dromasauria" is not recognised in modern cladistics-based taxonomy (where groups are based upon shared common ancestry). Rather than forming their own clade, phylogenetic analyses have found the various "dromasaurs" to be distributed individually throughout the evolutionary tree of basal anomodonts. In particular, Galeops is notably found to consistently be much closer to the dicynodonts than to the other "dromasaurs". Some earlier studies have inferred or even recovered a close sister-relationship between Galechirus and Galepus in a clade, to which the name Galechiridae has sometimes been applied. [2] [3] However, more recent phylogenetic analyses incorporating more data and more complete samples of basal anomodonts have found them at separate points on the tree too. [4]

The cladogram below depicts the results of the phylogenetic analysis from Angielczyk and Kammerer (2017), with each of the three "dromasaurs" highlighted in light green: [4]

| Anomodontia | |||||||