| Aulacephalodon Temporal range: Late Permian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of A. peavoti in the Field Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | † Anomodontia |

| Clade: | † Dicynodontia |

| Family: | † Geikiidae |

| Genus: | † Aulacephalodon Seeley, 1898 |

| Type species | |

| Aulacephalodon bainii Seeley, 1898 (type) | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

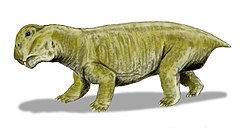

Aulacephalodon ("furrow-head tooth") is an extinct genus of medium-sized dicynodonts, or non-mammalian synapsids, that lived during late Permian period. Individuals of Aulacephalodon are commonly found in the Lower Beaufort Group of the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa. Rising to dominance during the Late Permian, Aulacephalodon was among the largest terrestrial vertebrate herbivores until its extinction at the end of the Permian. [2] Three species are typically recognized, the type species, A. bainii (named in 1898), a second species, A. peavoti (named in 1921), and a third species, A. kapoliwacela (named in 2025). However, debate exists among paleontologists if A. peavoti is a true member of the genus Aulacephalodon. [2] Aulacephalodon belongs to the family Geikiidae, a family of dicynodonts generally characterized by their short, broad skulls and large nasal bosses. [3] Sexual dimorphism has been identified in A. bainii. [4]