Description and paleobiology

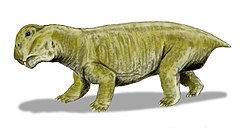

Eosimops was a small, non-mammalian synapsid. It was around 34 cm in length (13.4 in.), roughly the size of a prairie dog. [1] It had a long cylindrical body, with sprawling, clawed limbs which it probably used for digging. Eosimops had two long tusks on its upper jaw, [3] and a cutting keratinized beak [4] for processing vegetation. It likely fed on leaves, stems, roots, and fleshy parts of plants. It has been suggested that some dicynodonts had hair, so Eosimops may have sported small hairs for insulation and tactile sensation. Its short and stocky proportions could have also aided in heat retention. [5]

Skull

Like other pylaecephalids, Eosimops had a roughly square skull that sported caniform tusks. These tusks have been interpreted as representing sexual dimorphism within the closely related genus Diictodon , [6] so may have been used for sexual selection. At least one postcanine tooth was present on the dentary blade. Its skull shape is described as being similar to that of its fellow pylaecephalid Robertia , but likely attaining larger sizes. [1]

Eosimops had indistinguishably fused premaxillae, with the single element forming the anterior portion of the snout and alveolar margin along with the anterior edge of the external nares. The premaxilla forms part of the secondary pallet, and bears two sets of paired anterior ridges as well as a single median posterior palatal ridge. A dorsally directed portion of the premaxilla with a rounded edge projects between the nasals, diagnostic of dicynodonts thanks to the narrow groove along its midline. [1] The left and right dentaries of Eosimops' mandible were fused, and the anterior surface sported a vascular foramina which was likely associated with a keratinaceous beak. [4] Mandibular teeth were present, along with a well-developed dentary table. [4] The dorsal margin of the symphysis is upturned, forming a cutting edge at the front of the lower jaw. [1] The jaw joint facilitated a fore and aft sliding motion, allowing the animal to process vegetation effectively. [7]

Skeleton

Eosimops had a cylindrical body with 47 vertebrae, much like its other dicynodont relatives. Six of these were cervical, and 23 were dorsal. In the one full specimen recovered, no atlantal or axial ribs were observed. Whether or not this represents a true absence or incomplete preservation is uncertain. The dorsal ribs of Eosimops were long and relatively thin, and there was a ventral component to the curvature of the thorax. The sacral ribs were laterally expanded and robust. Its body likely resembled that of its close relatives Robertia and Diictodon. Typical of dicynodonts, the humerus of Eosimops sported expanded proximal and distal ends. It had a typical anomodont phalangeal formula of 2-3-3-3-3 on its forelimbs. While the hind limbs were not preserved well enough to know for certain, it appears that this formula was present on the hind limbs as well. [1]

Both the fore and hind limbs possessed extended phalanges with long, flattened claws, which suggests that Eosimops was a digger. It had short limbs, and it likely had a sprawling posture similar to its close relative Diictodon. Like Diictodon, Eosimops likely used its forelimbs for postural support and digging and its hind limbs for impact loading. [8]

Diet

Like all other known dicynodonts Eosimops was herbivorous, using its horny beak to process plant matter. As it didn't have a well-developed mastication system in comparison to modern vertebrates and lacked a gastric mill, Eosimops likely had a well-developed digestive tract and focused on feeding on high-quality forage. This likely included gymnosperm plants, evidence of which has been found in dicynodont coprolites. [9]

Endothermy and hair

Dicynodonts, including Eosimops, have been suspected for some time to be endothermic. [10] In a histological study of the closely related Diictodon, another pylaecephalid, rapid bone growth is shown to be part of their early ontogeny. Continued growth during adult stages was also observed. [11] This rapid growth as well as moderately vascularized bones suggests that Diictodon could have been an endotherm, and that Eosimops could have been as well. This would be consistent with the hypothesis that more derived dicynodonts were endotherms, as endothermy would likely have been evolved early in the taxon's history.

Eosimops also potentially had hair. The discovery of hair remains in coprolites from carnivorous species that had consumed dicynodonts suggests that the hair was of dicynodont origin, [5] so hair could well be present in basal forms such as pylaecephalids. [12] This, along with Eosimops' stocky body proportions, would allow the animal to conserve generated heat. [5]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.