Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, resulting in a more "standing" quadrupedal posture, as opposed to the lower sprawling posture of many reptiles and amphibians.

Cynodontia is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian, and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extinct ancestors and close relatives (Mammaliaformes), having evolved from advanced probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic.

Probainognathus meaning “progressive jaw” is an extinct genus of cynodonts that lived around 235 to 221.5 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Together with the genus Bonacynodon from Brazil, Probainognathus forms the family Probainognathidae. Probainognathus was a relatively small, carnivorous or insectivorous cynodont. Like all cynodonts, it was a relative of mammals, and it possessed several mammal-like features. Like some other cynodonts, Probainognathus had a double jaw joint, which not only included the quadrate and articular bones like in more basal synapsids, but also the squamosal and surangular bones. A joint between the dentary and squamosal bones, as seen in modern mammals, was however absent in Probainognathus.

Thrinaxodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts, including the species T. liorhinus which lived in what are now South Africa and Antarctica during the Early Triassic. Thrinaxodon lived just after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event, its survival during the extinction may have been due to its burrowing habits.

Galesaurus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodont therapsid that lived between the Induan and the Olenekian stages of the Early Triassic in what is now South Africa. It was incorrectly classified as a dinosaur by Sir Richard Owen in 1859.

Ericiolacerta is an extinct genus of small therocephalian therapsids from the early Triassic of South Africa and Antarctica. Ericiolacerta, meaning "hedgehog lizard", was named by D.M.S. Watson in 1931. The species E. parva is known from the holotype specimen which consists of a nearly complete skeleton found in the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone within the Katberg Formation of the Beaufort Group in South Africa, and from a partial jaw found in the Lower Triassic Fremouw Formation in Antarctica. Ericiolacerta was around 20 centimetres (7.9 in) in length, with long limbs and relatively small teeth. It probably ate insects and other small invertebrates. The therocephalians – therapsids with mammal-like heads – were abundant in Permian times, but only a few made it into the Triassic. Ericiolacerta was one of those. It is possible that they gave rise to the cynodonts, the only therapsid group to survive into post-Triassic times. Cynodonts gave rise to mammals.

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of eutheriodont therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their teeth, suggest that they were carnivores. Like other non-mammalian synapsids, therocephalians were once described as "mammal-like reptiles". Therocephalia is the group most closely related to the cynodonts, which gave rise to the mammals, and this relationship takes evidence in a variety of skeletal features. Indeed, it had been proposed that cynodonts may have evolved from therocephalians and so that therocephalians as recognised are paraphyletic in relation to cynodonts.

Galesauridae is an extinct family of cynodonts. Along with the family Thrinaxodontidae and the extensive clade Eucynodontia, it makes up the unranked taxon called Epicynodontia. Galesaurids first appeared in the very latest Permian period, just a million years before the greatest extinction of all time, the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

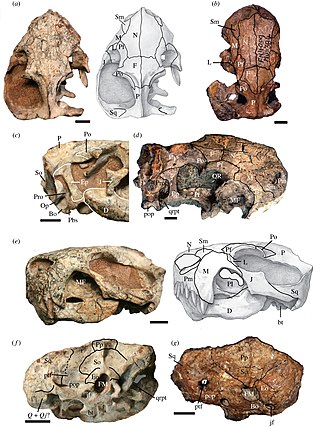

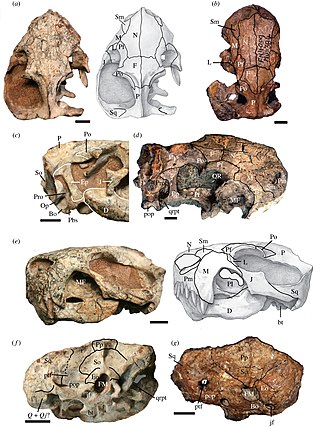

Euchambersia is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids that lived during the Late Permian in what is now South Africa and China. The genus contains two species. The type species E. mirabilis was named by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1931 from a skull missing the lower jaw. A second skull, belonging to a probably immature individual, was later described. In 2022, a second species, E. liuyudongi, was named by Jun Liu and Fernando Abdala from a well-preserved skull. It is a member of the family Akidnognathidae, which historically has also been referred by as the synonymous Euchambersiidae.

Moschorhinus is an extinct genus of therocephalian synapsid in the family Akidnognathidae with only one species: M. kitchingi, which has been found in the Late Permian to Early Triassic of the South African Karoo Supergroup. It was a large carnivorous therapsid, reaching 1.1–1.5 metres (3.6–4.9 ft) in total body length with the largest skull comparable to that of a lion in size, and had a broad, blunt snout which bore long, straight canines.

Theriognathus is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsid belonging to the family Whaitsiidae, known from fossils from South Africa, Zambia, and Tanzania. Theriognathus has been dated as existing during the Late Permian. Although Theriognathus means mammal jaw, the lower jaw is actually made up of several bones as seen in modern reptiles, in contrast to mammals. Theriognathus displayed many different reptilian and mammalian characteristics. For example, Theriognathus had canine teeth like mammals, and a secondary palate, multiple bones in the mandible, and a typical reptilian jaw joint, all characteristics of reptiles. It is speculated that Theriognathus was either carnivorous or omnivorous based on its teeth, and was suited to hunting small prey in undergrowth. This synapsid adopted a sleek profile of a mammalian predator, with a narrow snout and around 1 meter long. Theriognathus is represented by 56 specimens in the fossil record.

Broomistega is an extinct genus of temnospondyl in the family Rhinesuchidae. It is known from one species, Broomistega putterilli, which was renamed in 2000 from Lydekkerina putterilli Broom 1930. Fossils are known from the Early Triassic Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group in the Karoo Basin of present-day South Africa, a region that had been an enclave of Gondwana. Specimens of B. putterilli were once thought to represent young individuals of another larger rhinesuchid such as Uranocentrodon, but the species is now regarded as a paedomorphic taxon, possessing the features of juvenile rhinesuchids into adulthood.

Cromptodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts from the Triassic of Cerro Bayo de Portrerillos, Cerro de las Cabras Formation, Argentina, South America. It is known only from PVL 3858, a mandible.

Cynosaurus is an extinct genus of cynodonts. Remains have been found from the Dicynodon Assemblage Zone in South Africa. Cynosaurus was first described by Richard Owen in 1876 as Cynosuchus suppostus. Cynosaurus has been found in the late Permian period. Cyno- is derived from the Greek word kyon for dog and –sauros in Greek meaning lizard.

Platycraniellus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodonts from the Early Triassic. It is known from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Normandien Formation in South Africa. P. elegans is the only species in this genus based on the holotype specimen from the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History in Pretoria, South Africa. Due to limited fossil records for study, Platycraniellus has only been briefly described a handful of times.

Langbergia is an extinct genus of trirachodontid cynodont from the Early Triassic of South Africa. The type and only species L. modisei was named in 2006 after the farm where the holotype was found, Langberg 566. Langbergia was found in the Burgersdorp Formation in the Beaufort Group, a part of the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone. The closely related trirachodontids Trirachodon and Cricodon were found in the same area.

Pascualgnathus is an extinct genus of traversodontid cynodonts from the Middle Triassic of Argentina. Fossils have been found from the Río Seco de la Quebrada Formation of the Puesto Viejo Group. The type species P. polanskii was named in 1966.

Cricodon is an extinct genus of trirachodontid cynodonts that lived during the Early Triassic and Middle Triassic periods of Africa. A. W. Crompton named Cricodon based on the ring-like arrangement of the cuspules on the crown of a typical postcanine tooth. The epithet of the type species, C. metabolus, indicates the change in structure of certain postcanines resulting from replacement.

Abdalodon is an extinct genus of late Permian cynodonts, known by its only species A. diastematicus.Abdalodon together with the genus Charassognathus, form the clade Charassognathidae. This clade represents the earliest known cynodonts, and is the first known radiation of Permian cynodonts.

Vetusodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts belonging to the clade Epicynodontia. It contains one species, Vetusodon elikhulu, which is known from four specimens found in the Late Permian Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa. With a skull length of about 18 centimetres (7.1 in), Vetusodon is the largest known cynodont from the Permian. Through convergent evolution, it possessed several unusual features reminiscent of the contemporary therocephalian Moschorhinus, including broad, robust jaws, large incisors and canines, and small, single-cusped postcanine teeth.