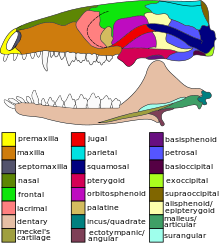

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida. Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye socket, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for the name "synapsid". The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

Cynodontia is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian, and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extinct ancestors and close relatives (Mammaliaformes), having evolved from advanced probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic.

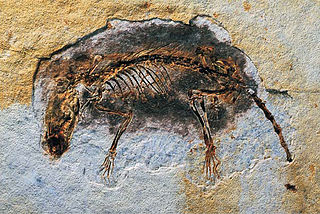

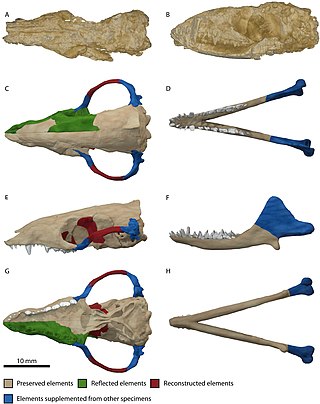

Morganucodon is an early mammaliaform genus that lived from the Late Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. It first appeared about 205 million years ago. Unlike many other early mammaliaforms, Morganucodon is well represented by abundant and well preserved material. Most of this comes from Glamorgan in Wales, but fossils have also been found in Yunnan Province in China and various parts of Europe and North America. Some closely related animals (Megazostrodon) are known from exquisite fossils from South Africa.

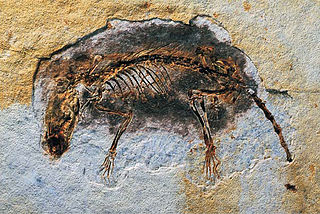

Allotheria is an extinct clade of mammals known from the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic. Shared characteristics of the group are the presence of lower molariform teeth equipped with longitudinal rows of cusps and enlarged incisors. Typically, the canine teeth are also lost. Allotheria includes Multituberculata, Gondwanatheria, and probably Haramiyida, although some studies have recovered haramiyidans to be basal mammaliaforms unrelated to multituberculates. Allotherians are often placed as crown group mammals, more closely related to living marsupials and placentals (Theria) than to monotremes or eutriconodonts, though some studies place the entirety of Allotheria outside of crown Mammalia.

Tribosphenida is a group (infralegion) of mammals that includes the ancestor of Hypomylos, Aegialodontia and Theria. It belongs to the group Zatheria. The current definition of Tribosphenida is more or less synonymous with Boreosphenida.

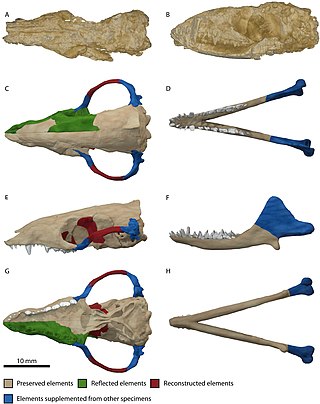

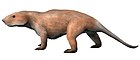

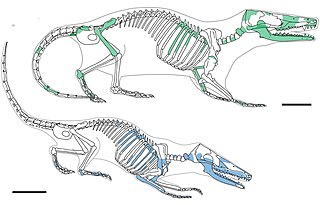

Megazostrodon is an extinct genus of basal mammaliaforms belonging to the order Morganucodonta. It is approximately 200 million years old. Two species are known: M. rudnerae from the Early Jurassic of Lesotho and South Africa, and M. chenali from the Late Triassic of France.

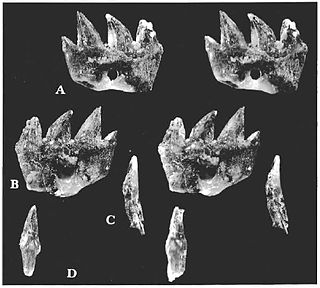

Eozostrodon is an extinct morganucodont mammaliaform. It lived during the Rhaetian stage of the Late Triassic. Eozostrodon is known from disarticulated teeth from South West England and estimated to have been less than 10 cm (3.9 in) in head-body length, slightly smaller than the similar-proportioned Megazostrodon.

Docodonta is an order of extinct Mesozoic mammaliaforms. They were among the most common mammaliaforms of their time, persisting from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous across the continent of Laurasia. They are distinguished from other early mammaliaforms by their relatively complex molar teeth. Docodontan teeth have been described as "pseudotribosphenic": a cusp on the inner half of the upper molar grinds into a basin on the front half of the lower molar, like a mortar-and-pestle. This is a case of convergent evolution with the tribosphenic teeth of therian mammals. There is much uncertainty for how docodontan teeth developed from their simpler ancestors. Their closest relatives may have been certain Triassic "symmetrodonts", namely Woutersia, and Delsatia. The shuotheriids, another group of Jurassic mammaliaforms, also shared some dental characteristics with docodontans. One study has suggested that shuotheriids are closely related to docodontans, though others consider shuotheriids to be true mammals, perhaps related to monotremes.

Sinoconodon is an extinct genus of mammaliamorphs that appears in the fossil record of the Lufeng Formation of China in the Sinemurian stage of the Early Jurassic period, about 193 million years ago. While sharing many plesiomorphic traits with other non-mammaliaform cynodonts, it possessed a special, secondarily evolved jaw joint between the dentary and the squamosal bones, which in more derived taxa would replace the primitive tetrapod one between the articular and quadrate bones. The presence of a dentary-squamosal joint is a trait historically used to define mammals.

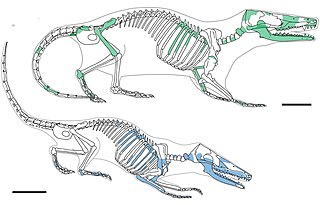

Tritylodontidae is an extinct family of small to medium-sized, highly specialized mammal-like cynodonts, with several mammalian traits including erect limbs, endothermy, and some details of the skeleton. They were the last-known family of the non-mammaliaform synapsids, persisting into the Early Cretaceous.

The evolution of mammals has passed through many stages since the first appearance of their synapsid ancestors in the Pennsylvanian sub-period of the late Carboniferous period. By the mid-Triassic, there were many synapsid species that looked like mammals. The lineage leading to today's mammals split up in the Jurassic; synapsids from this period include Dryolestes, more closely related to extant placentals and marsupials than to monotremes, as well as Ambondro, more closely related to monotremes. Later on, the eutherian and metatherian lineages separated; the metatherians are the animals more closely related to the marsupials, while the eutherians are those more closely related to the placentals. Since Juramaia, the earliest known eutherian, lived 160 million years ago in the Jurassic, this divergence must have occurred in the same period.

Eutriconodonta is an order of early mammals. Eutriconodonts existed in Asia, Africa, Europe, North and South America during the Jurassic and the Cretaceous periods. The order was named by Kermack et al. in 1973 as a replacement name for the paraphyletic Triconodonta.

Haramiyida is a possibly paraphyletic order of mammaliaform cynodonts or mammals of controversial taxonomic affinites. Their teeth, which are by far the most common remains, resemble those of the multituberculates. However, based on Haramiyavia, the jaw is less derived; and at the level of evolution of earlier basal mammals like Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, with a groove for ear ossicles on the dentary. Some authors have placed them in a clade with Multituberculata dubbed Allotheria within Mammalia. Other studies have disputed this and suggested the Haramiyida were not crown mammals, but were part of an earlier offshoot of mammaliaformes instead. It is also disputed whether the Late Triassic species are closely related to the Jurassic and Cretaceous members belonging to Euharamiyida/Eleutherodontida, as some phylogenetic studies recover the two groups as unrelated, recovering the Triassic haramiyidians as non-mammalian cynodonts, while recovering the Euharamiyida as crown-group mammals closely related to multituberculates.

Morganucodonta is an extinct order of basal Mammaliaformes, a group including crown-group mammals (Mammalia) and their close relatives. Their remains have been found in Southern Africa, Western Europe, North America, India and China. The morganucodontans were probably insectivorous and nocturnal, though like eutriconodonts some species attained large sizes and were carnivorous. Nocturnality is believed to have evolved in the earliest mammals in the Triassic as a specialisation that allowed them to exploit a safer, night-time niche, while most larger predators were likely to have been active during the day.

Shuotheriidae is a small family of Jurassic mammaliaforms whose remains are found in China, Great Britain and possibly Russia. They have been proposed to be close relatives of Australosphenida, together forming the clade Yinotheria. However, some studies suggest shuotheres are closer to therians than to monotremes, or that australosphenidans and therians are more closely related to each other than either are to shuotheres, with a 2024 study suggesting that shuotheriids were closely related to Docodonta outside of the Mammalia crown group.

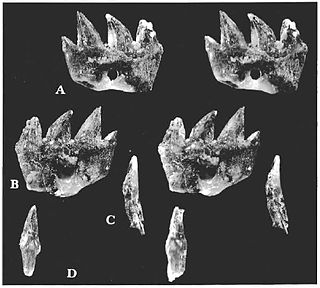

Kuehneotherium is an early mammaliaform genus, previously considered a holothere, that lived during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic Epochs and is characterized by reversed-triangle pattern of molar cusps. Although many fossils have been found, the fossils are limited to teeth, dental fragments, and mandible fragments. The genus includes Kuehneotherium praecursoris and all related species. It was first named and described by Doris M. Kermack, K. A. Kermack, and Frances Mussett in November 1967. The family Kuehneotheriidae and the genus Kuehneotherium were created to house the single species Kuehneotherium praecursoris. Modeling based upon a comparison of the Kuehneotherium jaw with other mammaliaforms indicates it was about the size of a modern-day shrew between 4 and 5.5 g at adulthood.

Megaconus is an extinct genus of allotherian mammal from the Middle Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Inner Mongolia, China. The type and only species, Megaconus mammaliaformis was first described in the journal Nature in 2013. Megaconus is thought to have been a herbivore that lived on the ground, having a similar posture to modern-day armadillos and rock hyraxes. Megaconus was in its initial description found to be member of a group called Haramiyida. A phylogenetic analysis published along its description suggested that haramiyidans originated before the appearance of true mammals, but in contrast, the later description of the haramiyidan Arboroharamiya in the same issue of Nature indicated that haramyidans were true mammals. If haramiyidans are not mammals, Megaconus would be one of the most basal ("primitive") mammaliaforms to possess fur, and an indicator that fur evolved in the ancestors of mammals and not the mammals themselves. However, later studies cast doubt on the euharamiyidan intrepretation, instead finding it to be a basal allotherian mammal.

Yinotheria is a proposed basal subclass clade of crown mammals uniting the Shuotheriidae, an extinct group of mammals from the Jurassic of Eurasia, with Australosphenida, a group of mammals known from the Jurassic to Cretaceous of Gondwana, which possibly include living monotremes. Today, there are only five surviving species of monotremes which live in Australia and New Guinea, consisting of the platypus and four species of echidna. Fossils of yinotheres have been found in Britain, China, Russia, Madagascar and Argentina. Contrary to other known crown mammals, they retained postdentary bones as shown by the presence of a postdentary trough. The extant members (monotremes) developed the mammalian middle ear independently.

Ichthyoconodon is an extinct genus of eutriconodont mammal from the Lower Cretaceous of Morocco. It is notable for having been found in a unique marine location, and the shape of its teeth suggests an unusual, potentially fish-eating ecological niche. Analysis suggests it is part of a group of gliding mammals that includes Volaticotherium.

Vilevolodon is an extinct, monotypic genus of volant, arboreal euharamiyids from the Oxfordian age of the Late Jurassic of China. The type species is Vilevolodon diplomylos. The genus name Vilevolodon references its gliding capabilities, Vilevol, while don is a common suffix for mammalian taxon titles. The species name diplomylos refers to the dual mortar-and-pestle occlusion of upper and lower molars observed in the holotype; diplo, mylos.