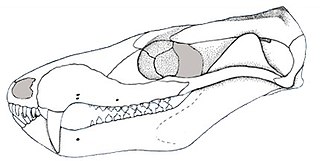

Synapsida is one of the two major clades of vertebrate animals in the group Amniota, the other being the Sauropsida. The synapsids were the dominant land animals in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic, but the only group that survived into the Cenozoic are mammals. Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye orbit, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for their name. The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

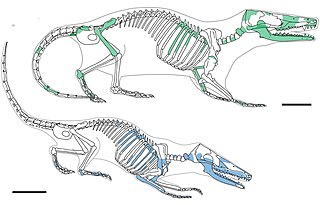

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, resulting in a more "standing" quadrupedal posture, as opposed to the lower sprawling posture of many reptiles and amphibians.

Cynodontia is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian, and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extinct ancestors and close relatives (Mammaliaformes), having evolved from advanced probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic.

Morganucodon is an early mammaliaform genus that lived from the Late Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. It first appeared about 205 million years ago. Unlike many other early mammaliaforms, Morganucodon is well represented by abundant and well preserved material. Most of this comes from Glamorgan in Wales, but fossils have also been found in Yunnan Province in China and various parts of Europe and North America. Some closely related animals (Megazostrodon) are known from exquisite fossils from South Africa.

Eozostrodon is an extinct morganucodont mammaliaform. It lived during the Rhaetian stage of the Late Triassic. Eozostrodon is known from disarticulated teeth from South West England and estimated to have been less than 10 cm (3.9 in) in head-body length, slightly smaller than the similar-proportioned Megazostrodon.

Docodonta is an order of extinct Mesozoic mammaliaforms. They were among the most common mammaliaforms of their time, persisting from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous across the continent of Laurasia. They are distinguished from other early mammaliaforms by their relatively complex molar teeth. Docodont teeth have been described as "pseudotribosphenic": a cusp on the inner half of the upper molar grinds into a basin on the front half of the lower molar, like a mortar-and-pestle. This is a case of convergent evolution with the tribosphenic teeth of therian mammals. There is much uncertainty for how docodont teeth developed from their simpler ancestors. Their closest relatives may have been certain Triassic "symmetrodonts", namely Woutersia, Delsatia.

Mammaliaformes is a clade that contains the crown group mammals and their closest extinct relatives; the group radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts. It is defined as the clade originating from the most recent common ancestor of Morganucodonta and the crown group mammals; the latter is the clade originating with the most recent common ancestor of extant Monotremata, Marsupialia, and Placentalia. Besides Morganucodonta and the crown group mammals, Mammaliaformes includes Docodonta and Hadrocodium.

Tritylodontidae is an extinct family of small to medium-sized, highly specialized mammal-like cynodonts, with several mammalian traits including erect limbs, endothermy and details of the skeleton. They were the last-known family of the non-mammaliaform synapsids, persisting into the Early Cretaceous.

The evolution of mammals has passed through many stages since the first appearance of their synapsid ancestors in the Pennsylvanian sub-period of the late Carboniferous period. By the mid-Triassic, there were many synapsid species that looked like mammals. The lineage leading to today's mammals split up in the Jurassic; synapsids from this period include Dryolestes, more closely related to extant placentals and marsupials than to monotremes, as well as Ambondro, more closely related to monotremes. Later on, the eutherian and metatherian lineages separated; the metatherians are the animals more closely related to the marsupials, while the eutherians are those more closely related to the placentals. Since Juramaia, the earliest known eutherian, lived 160 million years ago in the Jurassic, this divergence must have occurred in the same period.

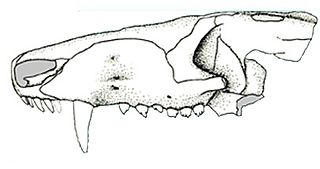

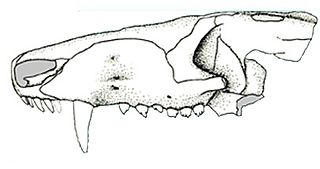

Prozostrodon is an extinct genus of probainognathian cynodonts that was closely related to mammals. The remains were found in Brazil and are dated to the Carnian age of the Late Triassic. The holotype has an estimated skull length of 6.7 centimetres (2.6 in), indicating that the whole animal may have been the size of a cat. The teeth were typical of advanced cynodonts, and the animal was probably a carnivore hunting reptiles and other small prey.

Eutriconodonta is an order of early mammals. Eutriconodonts existed in Asia, Africa, Europe, North and South America during the Jurassic and the Cretaceous periods. The order was named by Kermack et al. in 1973 as a replacement name for the paraphyletic Triconodonta.

Diarthrognathus is an extinct genus of tritheledontid cynodonts, known from fossil evidence found in South Africa and first described in 1958 by A.W. Crompton. The creature lived during the Early Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago. It was carnivorous and small, slightly smaller than Thrinaxodon, which was under 50 centimetres (20 in) long.

Haramiyida is a possibly paraphyletic order of mammaliaform cynodonts or mammals of controversial taxonomic affinites. Their teeth, which are by far the most common remains, resemble those of the multituberculates. However, based on Haramiyavia, the jaw is less derived; and at the level of evolution of earlier basal mammals like Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, with a groove for ear ossicles on the dentary. Some authors have placed them in a clade with Multituberculata dubbed Allotheria within Mammalia. Other studies have disputed this and suggested the Haramiyida were not crown mammals, but were part of an earlier offshoot of mammaliaformes instead. It is also disputed whether the Late Triassic species are closely related to the Jurassic and Cretaceous members belonging to Euharamiyida/Eleutherodontida, as some phylogenetic studies recover the two groups as unrelated, recovering the Triassic haramiyidians as non-mammalian cynodonts, while recovering the Euharamiyida as crown-group mammals closely related to multituberculates.

The evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles was an evolutionary process that resulted in the formation of the bones of the mammalian middle ear. These bones, or ossicles, are a defining characteristic of all mammals. The event is well-documented and important as a demonstration of transitional forms and exaptation, the re-purposing of existing structures during evolution.

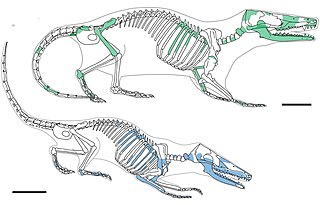

Morganucodonta is an extinct order of basal Mammaliaformes, a group including crown-group mammals (Mammalia) and their close relatives. Their remains have been found in Southern Africa, Western Europe, North America, India and China. The morganucodontans were probably insectivorous and nocturnal, though like eutriconodonts some species attained large sizes and were carnivorous. Nocturnality is believed to have evolved in the earliest mammals in the Triassic as a specialisation that allowed them to exploit a safer, night-time niche, while most larger predators were likely to have been active during the day.

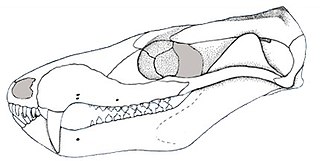

Kuehneotherium is an early mammaliaform genus, previously considered a holothere, that lived during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic Epochs and is characterized by reversed-triangle pattern of molar cusps. Although many fossils have been found, the fossils are limited to teeth, dental fragments, and mandible fragments. The genus includes Kuehneotherium praecursoris and all related species. It was first named and described by Doris M. Kermack, K. A. Kermack, and Frances Mussett in November 1967. The family Kuehneotheriidae and the genus Kuehneotherium were created to house the single species Kuehneotherium praecursoris. Modeling based upon a comparison of the Kuehneotherium jaw with other mammaliaforms indicates it was about the size of a modern-day shrew between 4 and 5.5 g at adulthood.

Brasilodon is an extinct genus of small, mammal-like cynodonts that lived in what is now Brazil during the Norian age of the Late Triassic epoch, about 225.42 million years ago. While no complete skeletons have been found, the length of Brasilodon has been estimated at 12 centimetres (4.7 in). Its dentition shows that it was most likely an insectivore. The genus is monotypic, containing only the species B. quadrangularis. Brasilodon belongs to the family Brasilodontidae, whose members were some of the closest relatives of mammals, the only cynodonts alive today. Two other brasilodontid genera, Brasilitherium and Minicynodon, are now considered to be junior synonyms of Brasilodon.

Lumkuia is an extinct genus of cynodont, fossils of which have been found in the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group in the South African Karoo Basin that date back to the early Middle Triassic. It contains a single species, Lumkuia fuzzi, which was named in 2001 on the basis of the holotype specimen BP/1/2669, which can now be found at the Bernard Price Institute in Johannesburg, South Africa. The genus has been placed in its own family, Lumkuiidae. Lumkuia is not as common as other cynodonts from the same locality such as Diademodon and Trirachodon.

Triconodontidae is an extinct family of small, carnivorous mammals belonging to the order Eutriconodonta, endemic to what would become Asia, Europe, North America and probably also Africa and South America during the Jurassic through Cretaceous periods at least from 190–66 mya.

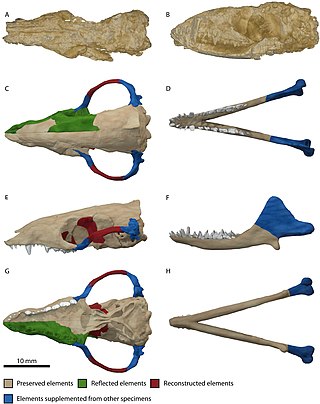

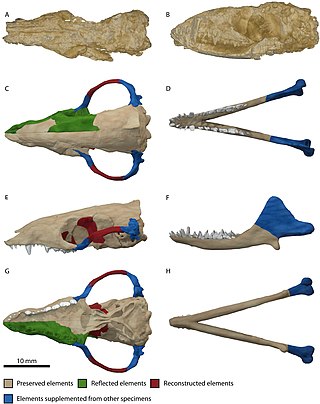

Wareolestes rex is a mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) rocks of England and Scotland. It was originally known from isolated teeth from England, before a more complete jaw with teeth was found in the Kilmaluag Formation of Skye, Scotland.