Probainognathidae is an extinct family of insectivorous cynodonts which lived in what is now South America during the Middle to Late Triassic. The family was established by Alfred Romer in 1973 and includes two genera, Probainognathus from the Chañares Formation of Argentina and Bonacynodon from the Dinodontosaurus Assemblage Zone of Brazil. Probainognathids were closely related to the clade Prozostrodontia, which includes mammals and their close relatives.

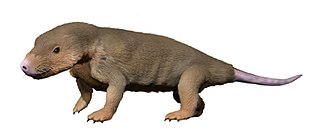

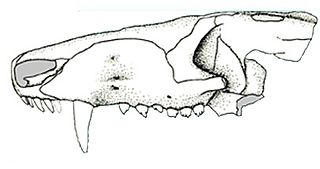

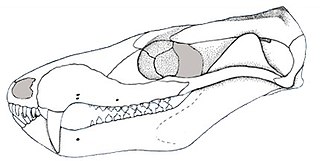

Probainognathus meaning “progressive jaw” is an extinct genus of cynodonts that lived around 235 to 221.5 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Together with the genus Bonacynodon from Brazil, Probainognathus forms the family Probainognathidae. Probainognathus was a relatively small, carnivorous or insectivorous cynodont. Like all cynodonts, it was a relative of mammals, and it possessed several mammal-like features. Like some other cynodonts, Probainognathus had a double jaw joint, which not only included the quadrate and articular bones like in more basal synapsids, but also the squamosal and surangular bones. A joint between the dentary and squamosal bones, as seen in modern mammals, was however absent in Probainognathus.

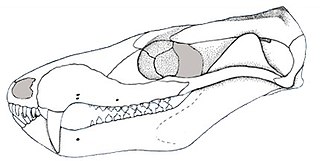

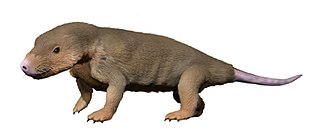

Thrinaxodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts, including the species T. liorhinus which lived in what are now South Africa and Antarctica during the Early Triassic. Thrinaxodon lived just after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event, its survival during the extinction may have been due to its burrowing habits.

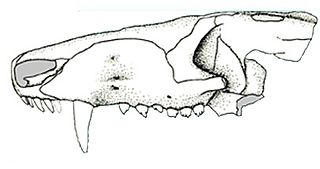

Galesaurus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodont therapsid that lived between the Induan and the Olenekian stages of the Early Triassic in what is now South Africa. It was incorrectly classified as a dinosaur by Sir Richard Owen in 1859.

Massetognathus is an extinct genus of plant-eating traversodontid cynodonts. They lived during the Triassic Period about 235 million years ago, and are known from the Chañares Formation in Argentina and the Santa Maria Formation in Brazil.

Bauria is an extinct genus of the suborder Therocephalia that existed during the Early and Middle Triassic period, around 246-251 million years ago. It belonged to the family Bauriidae. Bauria was probably a herbivore or omnivore. It lived in South Africa, specifically in the Burgersdorp Formation in South Africa.

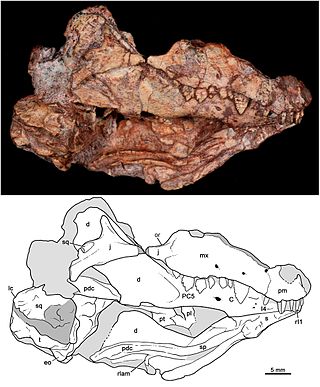

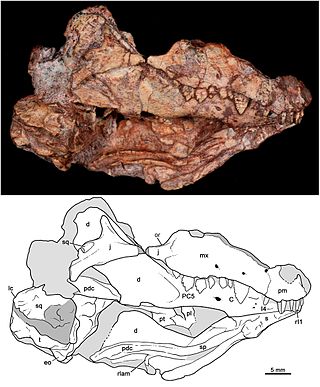

Prozostrodon is an extinct genus of probainognathian cynodonts that was closely related to mammals. The remains were found in Brazil and are dated to the Carnian age of the Late Triassic. The holotype has an estimated skull length of 6.7 centimetres (2.6 in), indicating that the whole animal may have been the size of a cat. The teeth were typical of advanced cynodonts, and the animal was probably a carnivore hunting reptiles and other small prey.

Gobiconodon is an extinct genus of carnivorous mammals belonging to the family Gobiconodontidae. Undisputed records of Gobiconodon are restricted to the Early Cretaceous of Asia and North America, but isolated teeth attributed to the genus have also been described from formations in England and Morocco dating as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Species of Gobiconodon varied considerably in size, with G. ostromi, one of the larger species, being around the size of a modern Virginia opossum. Like other gobiconodontids, it possessed several speciations towards carnivory, such as shearing molariform teeth, large canine-like incisors and powerful jaw and forelimb musculature, indicating that it probably fed on vertebrate prey. Unusually among predatory mammals and other eutriconodonts, the lower canines were vestigial, with the first lower incisor pair having become massive and canine-like. Like the larger Repenomamus there might be some evidence of scavenging.

Brasilodon is an extinct genus of small, mammal-like cynodonts that lived in what is now Brazil during the Norian age of the Late Triassic epoch, about 225.42 million years ago. While no complete skeletons have been found, the length of Brasilodon has been estimated at 12 centimetres (4.7 in). Its dentition shows that it was most likely an insectivore. The genus is monotypic, containing only the species B. quadrangularis. Brasilodon belongs to the family Brasilodontidae, whose members were some of the closest relatives of mammals, the only cynodonts alive today. Two other brasilodontid genera, Brasilitherium and Minicynodon, are now considered to be junior synonyms of Brasilodon.

Progalesaurus is an extinct genus of galesaurid cynodont from the early Triassic. Progalesaurus is known from a single fossil of the species Progalesaurus lootsbergensis, found in the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Balfour Formation. Close relatives of Progalesaurus, other galesaurids, include Galesaurus and Cynosaurus. Galesaurids appeared just before the Permian-Triassic extinction event, and disappeared from the fossil record in the Middle-Triassic.

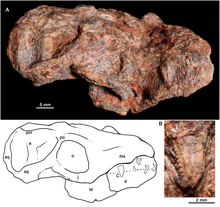

Platycraniellus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodonts from the Early Triassic. It is known from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Normandien Formation in South Africa. P. elegans is the only species in this genus based on the holotype specimen from the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History in Pretoria, South Africa. Due to limited fossil records for study, Platycraniellus has only been briefly described a handful of times.

Arctotraversodon is an extinct genus of traversodontid cynodonts from the Late Triassic of Canada. Fossils first described from the Wolfville Formation in Nova Scotia in 1984 represented the first known traversodontid from North America. The type and only species is A. plemmyridon and is represented by teeth and several dentary bones.

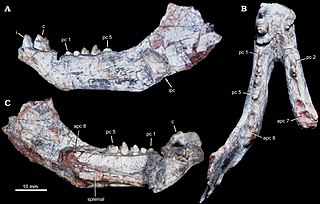

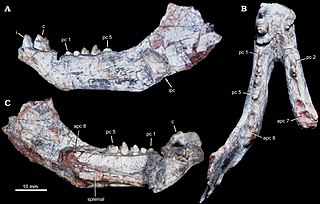

Candelariodon is an extinct genus of carnivorous probainognathian cynodonts from the Middle to Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation of the Paraná Basin in Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil. Candelariodon is known from a partial mandible having some complete teeth. It was first named by Téo Veiga de Oliveira, Cesar Leandro Schultz, Marina Bento Soares and Carlos Nunes Rodrigues in 2011 and the type species is Candelariodon barberenai.

Alemoatherium is an extinct genus of prozostrodontian cynodont which lived in the Late Triassic of Brazil. It contains a single species, A. huebneri, named in 2017 by Agustín Martinelli and colleagues. The genus is based on UFSM 11579b, a left lower jaw (dentary) found in the Alemoa Member of the Santa Maria Formation, preserving the late Carnian-age Hyperodapedon Assemblage Zone. Alemoatherium was among the smallest species of cynodonts found in the rich synapsid fauna of the Santa Maria Formation. Its blade-like four-cusped postcanine teeth show many similarities with those of dromatheriids, an obscure group of early prozostrodontians.

Aleodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts that lived from the Middle to the Late Triassic. Relatively few analyses have been conducted to identify the phylogenetic placement of Aleodon, however those that have place Aleodon as a sister taxon to Chiniquodon. Two species of Aleodon are recognized: A. brachyramphus which was discovered in Tanzania, and A. cromptoni which was discovered most recently in Brazil.

Abdalodon is an extinct genus of late Permian cynodonts, known by its only species A. diastematicus.Abdalodon together with the genus Charassognathus, form the clade Charassognathidae. This clade represents the earliest known cynodonts, and is the first known radiation of Permian cynodonts.

Etjoia is an extinct genus of traversodontid cynodonts that lived during the Middle Triassic or Late Triassic period in southern Africa. This medium-sized omnivorous cynognathian provides important information on the dental evolution of early diverging gomphodonts and traversodontids.

Pseudotherium is an extinct genus of prozostrodontian cynodonts from the Late Triassic of Argentina. It contains one species, P. argentinus, which was first described in 2019 from remains found in the La Peña Member of the Ischigualasto Formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin.

Vetusodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts belonging to the clade Epicynodontia. It contains one species, Vetusodon elikhulu, which is known from four specimens found in the Late Permian Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa. With a skull length of about 18 centimetres (7.1 in), Vetusodon is the largest known cynodont from the Permian. Through convergent evolution, it possessed several unusual features reminiscent of the contemporary therocephalian Moschorhinus, including broad, robust jaws, large incisors and canines, and small, single-cusped postcanine teeth.

Santacruzgnathus is an extinct genus of small cynodonts from the Late Triassic (Carnian) Santacruzodon Assemblage Zone of Brazil. It contains one species, S. abdalai. Santacruzgnathus is known from a single partial lower jaw with four postcanine teeth, only one of which is well-preserved. Some features of the specimen, including the slender shape of the jaw and the incipiently double-rooted teeth, indicate that the animal was an early member of Prozostrodontia, a group that includes mammals and their close relatives.