| Vaginismus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vaginism, genito-pelvic pain disorder [1] |

| |

| Muscles included | |

| Specialty | Gynecology, urology, sexual medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain with sex or any form of vaginal penetration [2] |

| Usual onset | When first attempting to insert a tampon or at first sexual intercourse [3] |

| Causes | Fear of pain [3] |

| Risk factors | History of sexual assault, endometriosis, vaginitis, prior episiotomy [2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on the symptoms and examination [2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dyspareunia, [4] Vulvodynia [5] |

| Treatment | Behavior therapy, gradual vaginal dilatation [2] |

| Prognosis | Generally good with treatment [6] |

| Frequency | 1–7% of the female population [5] |

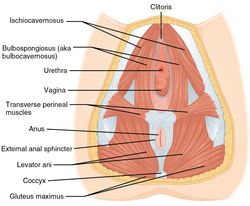

Vaginismus is a condition in which involuntary muscle spasm interferes with vaginal intercourse or other penetration of the vagina. [2] This often results in pain with attempts at sex. [2] Often it begins when vaginal intercourse is first attempted. [3] Vaginismus may be considered an older term for pelvic floor dysfunction. [7]

Contents

- Signs and symptoms

- Causes

- Primary vaginismus

- Secondary vaginismus

- Mechanism

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Psychological

- Physical

- Neuromodulators

- Epidemiology

- History

- In popular culture

- See also

- References

- Further reading

The formal diagnostic criteria specifically require interference during vaginal intercourse and a desire for intercourse, but the term vaginismus is sometimes used more broadly to refer to any muscle spasm occurring during the insertion of objects into the vagina, sexually motivated or otherwise, including speculums and tampons. [6] [8]

The underlying cause is generally a fear that penetration will hurt. [3] Risk factors include a history of sexual assault, endometriosis, vaginitis, or a prior episiotomy. [2] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms and examination. [2] It requires there to be no anatomical or physical problems (e.g., pelvic floor dysfunction, vulvodynia, vestibulodynia, etc.) and a desire for penetration. [3] [9]

Treatment may include behavior therapy such as graduated exposure therapy and gradual vaginal dilation. [2] [3] Surgery is not generally indicated. [6] Botulinum toxin (botox), a muscle spasm treatment, is being studied. [2] There are no epidemiological studies of the prevalence of vaginismus. [10] Estimates of how common the condition is are varied. [11] One textbook estimates that 0.5% of women are affected, [2] but rates in clinical settings indicate that 5–17% of women experience vaginismus. [10] Outcomes are generally good with treatment. [6]