The 2000 Pacific hurricane season was an above-average Pacific hurricane season, although most of the storms were weak and short-lived. There were few notable storms this year. Tropical storms Miriam, Norman, and Rosa all made landfall in Mexico with minimal impact. Hurricane Daniel briefly threatened the U.S. state of Hawaii while weakening. Hurricane Carlotta was the strongest storm of the year and the second-strongest June hurricane in recorded history. Carlotta killed 18 people when it sank a freighter. Overall, the season was significantly more active than the previous season, with 19 tropical storms. In addition, six hurricanes developed. Furthermore, there were total of two major hurricanes.

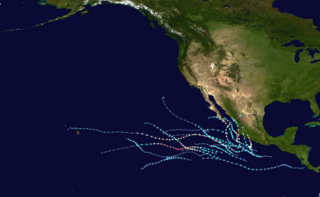

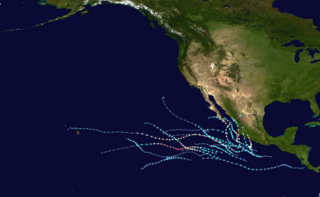

The 1994 Pacific hurricane season was the final season of the eastern north Pacific's consecutive active hurricane seasons that started in 1982. The season officially started on May 15, 1994, in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1, 1994, in the central Pacific, and lasted until November 30, 1994. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The first tropical cyclone formed on June 18, while the last system dissipated on October 26. This season, twenty-two tropical cyclones formed in the north Pacific Ocean east of the dateline, with all but two becoming tropical storms or hurricanes. A total of 10 hurricanes occurred, including five major hurricanes. The above average activity in 1994 was attributed to the formation of the 1994–95 El Niño.

The 1988 Pacific hurricane season was the least active Pacific hurricane season since 1981. It officially began May 15, in the eastern Pacific, and June 1, in the central Pacific and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The first named storm, Tropical Storm Aletta, formed on June 16, and the last-named storm, Tropical Storm Miriam, was previously named Hurricane Joan in the Atlantic Ocean before crossing Central America and re-emerging in the eastern Pacific; Miriam continued westward and dissipated on November 2.

The 2012 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season that saw an unusually high number of tropical cyclones pass west of the Baja California Peninsula. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the central Pacific (from 140°W to the International Date Line, north of the equator; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year. This season's first system, Tropical Storm Aletta, formed on May 14, and the last, Tropical Storm Rosa, dissipated on November 3.

The 2006 Pacific hurricane season was the first above-average season since 1997 which produced twenty-five tropical cyclones, with nineteen named storms, though most were rather weak and short-lived. There were eleven hurricanes, of which six became major hurricanes. Following the inactivity of the previous seasons, forecasters predicted that season would be only slightly above active. It was also the first time since 2003 in which one cyclone of at least tropical storm intensity made landfall. The season officially began on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year.

The 2016 Pacific hurricane season was tied as the fifth-most active Pacific hurricane season on record, alongside the 2014 season. Throughout the course of the year, a total of 22 named storms, 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes were observed within the basin. Although the season was very active, it was considerably less active than the previous season, with large gaps of inactivity at the beginning and towards the end of the season. It officially started on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific ; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, tropical development is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Hurricane Pali on January 7, the earliest Central Pacific tropical cyclone on record. After Pali, however, no tropical cyclones developed in either region until a short-lived depression on June 6. Also, there were no additional named storms until July 2, when Tropical Storm Agatha formed, becoming the latest first-named Eastern Pacific tropical storm since Tropical Storm Ava in 1969.

The 2017 Pacific hurricane season was an above average Pacific hurricane season in terms of named storms, though less active than the previous three, featuring eighteen named storms, nine hurricanes, and four major hurricanes. Despite the considerable amount of activity, most of the storms were weak and short-lived. The season officially started on May 15 in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the respective regions. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated in 2017 by the formation of the season's first named storm, Tropical Storm Adrian, on May 9. At the time, this was the earliest formation of a tropical storm on record in the eastern Pacific basin proper. The season saw near-average activity in terms of accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), in stark contrast to the extremely active seasons in 2014, 2015, and 2016; and for the first time since 2012, no tropical cyclones formed in the Central Pacific basin. However, for the third year in a row, the season featured above-average activity in July, with the ACE value being the fifth highest for the month. Damage across the basin reached $375.28 million (2017 USD), while 45 people were killed by the various storms.

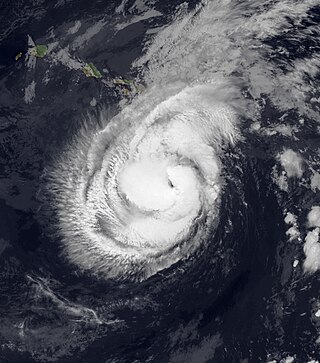

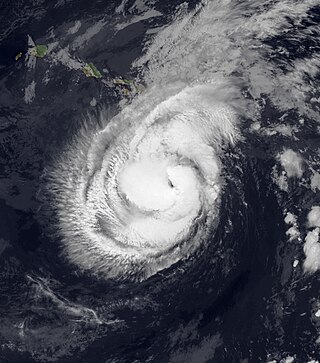

Hurricane Genevieve, also referred to as Typhoon Genevieve, was the first tropical cyclone to track across all three northern Pacific basins since Hurricane Dora in 1999. Genevieve developed from a tropical wave into the eighth tropical storm of the 2014 Pacific hurricane season well east-southeast of Hawaii on July 25. However, increased vertical wind shear caused it to weaken into a tropical depression by the following day and degenerate into a remnant low on July 28. Late on July 29, the system regenerated into a tropical depression, but it weakened into a remnant low again on July 31, owing to vertical wind shear and dry air.

The 2021 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season, with above-average activity in terms of number of named storms, but below-average activity in terms of major hurricanes, as 19 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes formed in all. It also had a near-normal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE). The season officially began on May 15, 2021 in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1, 2021, in the Central Pacific in the Northern Hemisphere. The season ended in both regions on November 30, 2021. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific and are adopted by convention. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Andres on May 9, which was the earliest forming tropical storm on record in the Eastern Pacific. Conversely, 2021 was the second consecutive season in which no tropical cyclones formed in the Central Pacific.

The 2022 Pacific hurricane season was a slightly above average hurricane season in the eastern North Pacific basin, with nineteen named storms, ten hurricanes, and four major hurricanes. Two of the storms crossed into the basin from the Atlantic. In the central North Pacific basin, no tropical cyclones formed. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central; both ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific and are adopted by convention.

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season was a very active and extremely destructive Atlantic hurricane season, producing 18 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes; it was also the first since 2019 to feature multiple Category 5 hurricanes. Additionally, the season had the highest accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating since 2020, with a value of 161.6 units. The season officially began on June 1, and ended on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, have historically described the period in each year when most subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic Ocean.

Hurricane Douglas was a strong tropical cyclone that became the closest passing Pacific hurricane to the island of Oahu on record, surpassing the previous record held by Hurricane Dot in 1959. The eighth tropical cyclone, fifth named storm, first hurricane, and first major hurricane of the 2020 Pacific hurricane season, Douglas originated from a tropical wave which entered the basin in mid-July. Located in favorable conditions, the wave began to organize on July 19. It became a tropical depression on July 20 and a tropical storm the following day. After leveling off as a strong tropical storm due to dry air, Douglas began rapid intensification on July 23, becoming the season's first major hurricane the following day and peaking as a Category 4 hurricane. After moving into the Central Pacific basin, Douglas slowly weakened as it approached Hawaii. The storm later passed north of the main islands as a Category 1 hurricane, passing dangerously close to Oahu and Kauai, causing minimal damage, and resulting in no deaths or injuries. Douglas weakened to tropical storm status on July 28, as it moved away from Hawaii, before degenerating into a remnant low on July 29 and dissipating on the next day.

The 2023 Pacific hurricane season was an active and destructive Pacific hurricane season. In the Eastern Pacific basin, 17 named storms formed; 10 of those became hurricanes, of which 8 strengthened into major hurricanes – double the seasonal average. In the Central Pacific basin, no tropical cyclones formed for the fourth consecutive season, though four entered into the basin from the east. Collectively, the season had an above-normal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) value of approximately 168 units. This season saw the return of El Niño and its associated warmer sea surface temperatures in the basin, which fueled the rapid intensification of several powerful storms. It officially began on May 15, 2023 in the Eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the Central; both ended on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific.

The 2021 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active hurricane season, with above-average tropical activity in terms of named storms, but featured below-average activity in terms of major hurricanes. It is the first season to have at least five systems make landfall in Mexico, the most since 2018. It was also the second consecutive season in which no tropical cyclones formed in the Central Pacific. The season officially began on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; both ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the eastern and central Pacific and are adopted by convention. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated this year by the formation of Tropical Storm Andres on May 9. This was the earliest forming tropical storm on record in the Eastern Pacific. The season effectively ended with the dissipation of Tropical Storm Terry, on November 10.

Hurricane Enrique was a Category 1 Pacific hurricane that brought heavy rainfall and flooding to much of western Mexico in late June 2021. The fifth named storm and first hurricane of the 2021 Pacific hurricane season, Enrique developed from a tropical wave the entered the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Nicaragua on June 22. In an environment conducive for intensification, the disturbance moved west-northwestward and developed into a tropical storm by 6:00 UTC on June 25, as it was already producing winds of 40 mph (65 km/h), and received the name Enrique. Enrique strengthened steadily within an environment of warm waters and low-to-moderate wind shear while continuing its northwestward motion. By 12:00 UTC on June 26, Enrique had intensified into a Category 1 hurricane as the storm turned more northwestward. Nearing the coast of Mexico, Enrique reached its peak intensity around 6:00 UTC the following day, with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 972 mbar (28.7 inHg). Enrique, passing closely offshore west-central Mexico, maintained its intensity for another 24 hours as it turned northward toward the Gulf of California. Turning back to the northwest on June 28, increasing wind shear and dry air caused the hurricane to weaken. Enrique dropped to tropical storm status at 18:00 UTC that day, and further weakened to a tropical depression on June 30 just to the northeast of Baja California. The depression was absorbed into a larger low pressure area to the southeast later that day.

Hurricane Olaf was a Category 2 Pacific hurricane that struck the Baja California Peninsula in September 2021. The fifteenth named storm and sixth hurricane of the 2021 Pacific hurricane season, the cyclone formed from an area of low pressure that developed off the southwestern coast of Mexico on September 5, 2021. The disturbance developed within a favorable environment, acquiring more convection and a closed surface circulation. The disturbance developed into Tropical Depression Fifteen-E by 18:00 UTC on September 7. The depression strengthened into a tropical storm and was named Olaf at 12:00 UTC the next day. Olaf quickly strengthened as it moved to the north-northwest, and was upgraded to a hurricane 24 hours after being named. Hurricane Olaf continued to intensify and reached peak intensity while its center was just offshore the southwestern coast of Baja California Sur, with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 975 mbar (28.8 inHg). Just after reaching peak intensity, the hurricane made landfall near San José del Cabo. Interaction with the mountainous terrain of the Baja California Peninsula caused Olaf to quickly weaken. It was downgraded to a tropical storm at 12:00 UTC on September 10. The system became devoid of convection later that day and degenerated to a remnant low by 06:00 UTC on September 11.

Hurricane Orlene was a powerful tropical cyclone that caused minor damage to the Pacific coast of Mexico in October 2022. The cyclone was the sixteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the 2022 Pacific hurricane season. Orlene originated from a low-pressure area off the coast of Mexico. Moving towards the north, Orlene gradually strengthened, becoming a hurricane on October 1 and reaching its peak intensity the following day with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h). Orlene made landfall just north of the Nayarit and Sinaloa border, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Soon afterward, Orlene rapidly weakened and became a tropical depression, eventually dissipating over the Sierra Madre Occidental late on October 4.

The 2024 Pacific hurricane season is the current tropical cyclone season in the Pacific Ocean east of the International Date Line (IDL) in the Northern Hemisphere. It officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central Pacific ; it will end in both on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific. The season's first system, Tropical Storm Aletta, developed on July 4.

Hurricane Hone was a fairly long-lived tropical cyclone that impacted the U.S. state of Hawaii in August 2024. The eighth named storm and third hurricane of the 2024 Pacific hurricane season, Hone was also the first tropical cyclone to form in the North Central Pacific tropical cyclone basin since 2019. Hone developed from two disturbances that formed over the northeastern Pacific Ocean in late August 2024. The two disturbances eventually merged into a larger area of disturbed weather on August 20. The merged system steadily became more organized, and the development of persistent deep convection over its center led to its designation as Tropical Depression One-C on August 22. The depression strengthened into a tropical storm six hours later and was named Hone. Hone gradually strengthened as it approached Hawaii from the southeast. On August 25, Hone strengthened into a hurricane while located just south of Hawaii's Big Island. After passing near the islands with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h), Hone began to weaken as it continued westward away from Hawaii, and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center ultimately designated Hone as a post-tropical low near the International Date Line on September 1. However, the system continued to be monitored by the Japan Meteorological Agency and Joint Typhoon Warning Center, which designated Hone a tropical and subtropical depression, respectively, in the Western Pacific, until the storm dissipated several days later.