Evolution of Acadia’s borders

Origins

Several Indigenous peoples successively occupied the territory that would become Acadia. The most recent before European contact were the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, and Abenaki, whose cultures developed from the 6th century CE onward. [5] Martins Point is generally regarded as the boundary between Maliseet and Mi'kmaq territory, while Lepreau Point marked the divide between the Maliseet and the Passamaquoddy. [6] Portages connected these territories, and the peoples belonged to the Wabanaki Confederacy. [7] In any case, these boundaries were fluid because the territories were not permanently occupied; the economy was based on hunting and fishing. [6]

Indigenous boundaries had little or no impact on subsequent European borders. [6] However, the distribution of Indigenous nations was frequently shown on maps, and tribal names were sometimes used in place of territorial ones. [8]

Early European exploration

The Vikings reached North America around the year 1000 and named three regions—Helluland, Markland, and Vinland—whose exact locations and extents remain unknown. [9] In any event, none of their boundaries survived their departure. [10]

- The 1570 Skálholt Map showing Viking possessions.

- Probable route of Viking explorers.

Several largely unsubstantiated theories exist about early pre-Columbian exploration and settlement of Acadia, including voyages by the Irish saint Saint Brendan around 530, the Welsh prince Madog around 1170, Malians in the 12th–13th centuries, the Knights Templar in the 14th century, the Zeno brothers around 1390, and the Chinese admiral Zheng He in 1421. [11] Phantom islands and imaginary places such as Drogeo and Norumbega are associated with these voyages. Norumbega appeared on maps until the early 17th century; its last mention came in 1613 when Pierre Biard wrote that the St. Croix River flowed through it. [8]

In any case, Christopher Columbus reached the Americas in 1492. The papal bull Inter caetera (1493) granted Spain all lands west and south of a line 100 leagues (418 km (260 mi)) west of the Azores and Cape Verde. [9] The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) moved the line to 370 leagues (1,770 km (1,100 mi)) west of Cape Verde. [9] In both cases, the future Acadia fell within the Spanish sphere, but the demarcation was ignored by other European powers, including Spain and Portugal, and soon fell into disuse. [10]

- The Treaty of Tordesillas.

- Demarcation line according to Inter caetera and Tordesillas (Spain west, Portugal east).

Many explorers visited the region in the 15th and early 16th centuries, including John Cabot for England in 1497 and João Álvares Fagundes for Portugal around 1520. [10] Fagundes explored and named several areas, including Newfoundland, present-day Nova Scotia, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon; he may have claimed them for Portugal, though this is unlikely. [12] Early explorers initially mistook the land for Asia but soon realized they had found a new continent and sought a passage to Asia. [9] Maps of the period often used flags to denote possession, but boundaries remained vague. [9] Exploration did not necessarily confer legal possession but formed the basis for future claims. [9] European fishermen were already familiar with the coasts. [10]

French Acadia (1604–1713)

French Acadia refers to the period from its founding in 1604 until its final conquest by Britain in 1713. It was not always called Acadia during this time, nor was it continuously under French sovereignty. [13]

Official status within the Kingdom of France

New France is sometimes considered to comprise only the Canada colony or to include Acadia as well. [14] In practice, however, Acadia remained distinct, with its own governor. [14] Orders were supposed to pass through the Governor General of New France, but the French court sometimes dealt directly with Acadia’s governor. [14] Relations between Acadia and Canada were often tense, characteristic of two separate colonies; even Placentia (Plaisance) refused cooperation. [15]

A spirit of independence animated both Acadia and Canada. [16] The Abenaki lived around the Penobscot River, forming a buffer zone between Acadia and New England. [15]

Recognition

Spanish and Portuguese presence prevented England and France from colonizing south of the 30th parallel north. [17] The English focused around the 37th parallel and the French around the 45th, though the French were slow to establish settlements. [17]

The name “Acadia” was probably first used in 1524 by Giovanni da Verrazzano, exploring for France, to describe the Delmarva Peninsula; only in the 17th century did it refer to a region roughly corresponding to the modern Maritime provinces. [17]

- Verrazzano’s voyage.

- Delmarva Peninsula, the first region called Acadia.

France sent Jacques Cartier in 1534 before formally claiming the territory. [9] Humphrey Gilbert took possession of Newfoundland (northeast of Acadia) for England in 1583, based on Cabot’s voyage. [9] The Colony of Virginia was chartered the same year without defined limits. [9] France then considered Acadia to include the Gulf of St. Lawrence coast extending southwest to an undetermined boundary with Virginia. [9]

In 1603, Henry IV of France, citing Verrazzano’s exploration, granted Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons a fur-trade monopoly and instructed him to found a colony between the 40th and 46th parallels—intended to run from Cape Cod to Cape Breton Island but actually bisecting the island. [9] This ignored English explorations in Maine in 1602–1603. [9] It was likely the first use of parallels as boundaries in Canadian history. [18]

- Gulf of St. Lawrence.

- Jacques Cartier’s first voyage (1534).

- Newfoundland.

- Modern Virginia.

Early settlement attempts

Aymar de Chaste received the New France trade monopoly in 1603 and sent François Gravé du Pont and Samuel de Champlain, but no settlement was founded. [19]

Acadia was founded in 1604 by Pierre Dugua de Mons on Sainte-Croix Island, now in Maine near the northern shore of the Bay of Fundy. [17] An earlier colony on Sable Island (1598–1603) had failed. [19] Acadia became one of the first regions in North America to be accurately mapped, by Champlain in 1604. [20] The Sainte-Croix settlement failed, and Port-Royal was established in 1605 on the southern shore of the Bay of Fundy. [21]

- Acadia 1604–1607, showing Champlain’s and Dugua’s expeditions.

- Acadia 1610–1613, showing settlements and Indigenous nations.

Beginning of hostilities

From the outset, England coveted Acadia’s strategic position and repeatedly attacked it. [22] Most English attacks aimed to push Acadia’s border eastward to the Kennebec River and then the Penobscot River. [23] The French mainly tried to disrupt Boston. [23] The French founded no permanent settlements west of the St. Croix River. [24] Most attacks failed or were abandoned due to poor organization or weather. [23] Governors frequently moved the capital and received little military or financial support, contributing to instability. [25]

In 1606, the Virginia Company received a charter from James I for Virginia between the 34th and 45th parallels, ignoring Acadia’s boundaries. [18] The English founded the short-lived Popham Colony in Maine in 1607. [26] When the French settled Mount Desert Island in 1613, the English destroyed it and captured Port-Royal, basing their claim on Cabot’s voyage. [27]

In 1620, James I replaced the Virginia Company with the Plymouth Council for New England, granting land from the Atlantic to the Pacific between the 40th and 48th parallels—encompassing Acadia and the nascent Canada colony. [28] The modern 49th parallel border is coincidental. [8]

Nova Scotia for the first time (1621–1632)

From 1613, Scotland claimed a colony called Nova Scotia, roughly covering French Acadia east of the St. Croix River and a line drawn due north. [18] In 1621, James VI and I granted it to his favorite Sir William Alexander. [18] Part of the present Canada–US border derives from this grant. [8] It was the first North American territory delimited by precise, identifiable geographical features. [18]

Later in 1621, the Plymouth Council granted Alexander the “territory of Sagadahock” between the St. Croix and Kennebec rivers. [29] In 1622, John Mason and Ferdinando Gorges received land between the Kennebec and Merrimack, named the Province of Maine; it was split in 1629 into Maine and New Hampshire. [30]

In 1627, the Company of One Hundred Associates received a monopoly over New France, defined as stretching from Newfoundland to the Great Lakes, the Arctic Circle to Florida—thus including Acadia and English possessions. [18] War broke out that year between France and England. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632) partially ended it and returned Acadia to France. [18]

The Nova Scotia grant was reconfirmed in 1625 and 1633. [8] The colony was divided into New Alexandria (north) and New Caledonia (south) across the Isthmus of Chignecto and Bay of Fundy—resembling modern New Brunswick and Nova Scotia without direct connection. [8] Scottish settlers arrived in 1629 at Cape Breton and Port-Royal. [18]

Meanwhile, Canada was briefly granted to Alexander in 1628; the grant lapsed after 1632. [8] Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour received a baronetcy in 1630 from Cape Fourchu (near Yarmouth) to Mirliguèche (near Lunenburg), implying this was the sole “Acadia”. [31]

- Sir William Alexander.

- St. Croix River with modern borders.

British Acadia (1713–1763)

British Acadia describes the region of Acadia under British control from 1713 to 1763. [32]

Treaty of Utrecht and its interpretation (1713)

The British conquest of Acadia was formalized by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. [33]

The Most Christian King shall restore to the Queen of Great Britain, on the day of the exchange of the ratifications of this present Treaty of Peace, letters and authentic acts, which shall serve as evidence of the cession, in perpetuity, to the Queen and to the Crown of Great Britain, of the island of Saint Christopher, which shall henceforth be possessed alone by British subjects; of Nova Scotia, or Acadia, in its entirety, according to its ancient limits, as also of the town of Port Royal, now called Annapolis Royal; and generally of all that depends on the said lands and islands of the said country, with the sovereignty [...]. [33]

In practice, France retained Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean, along with other holdings such as Anticosti Island and fishing rights on the French Shore of Newfoundland. [note 1] [18] The treaty equated Acadia with Nova Scotia, despite France's longstanding claim that the colony extended to the Kennebec River or at least the Penobscot River. [34] From the perspective of Massachusetts, the treaty restored the territory of Sagadahock and Nova Scotia, while Nova Scotia's new governor viewed the colony as encompassing all of former Acadia with its western boundary at the St. George River. [34] Great Britain regarded Acadia (and thus Nova Scotia) as extending north to the St. Lawrence River. [34] France, however, limited Acadia (and Nova Scotia) to the southern portion of the peninsula, [34] arguing that it was not the pre-1710 Acadia but a different one "according to its ancient limits." [35] These divergent views of Acadia were reflected in maps produced by both powers. [34] The British did not immediately occupy the continental portion of the territory after the treaty's signing, implying continued French sovereignty there. [34]

- Île Royale, now Cape Breton Island.

- Île Saint-Jean, now Prince Edward Island.

- The French Shore of Newfoundland, 1713–1904.

- Anticosti Island.

The French began claiming the continental portion around 1720. [35] In 1751, they built Fort Beauséjour on the north bank of the Missaguash River, while the British constructed Fort Lawrence on the south bank, effectively recognizing the French position de facto; this marked the third time the Isthmus of Chignecto served as a boundary. [34]

Despite boundary uncertainties, the English granted the township of Harrington along the Saint John River in 1732, though the grant was soon forgotten. [36]

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and boundary commission (1748–1755)

In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) effected no changes to the respective positions. [34] The treaty provided for a bilateral commission in 1750 to delimit Acadia's boundaries, which yielded no results and was dissolved. Nonetheless, the commission's conferences and published volumes preserved many lost or rare documents. [37]

The boundary between Massachusetts and Nova Scotia remained practically undefined; Massachusetts proposed several solutions to Nova Scotia, which deferred the matter to the Crown. [34] In 1762, the two colonies agreed not to grant lands in the undefined area until the boundary was clarified. [34]

A bilateral commission was also established to delimit the boundary at the Isthmus of Chignecto, but it too failed. [38] The Acadians were deported between 1755 and 1763, but one-third had returned by the end of the 18th century. [39] The English forced returning Acadians to settle in small, dispersed groups; most former Acadian lands were granted to English settlers. [39]

Expulsion of the Acadians (1755–1763)

Partition of Acadia

In 1763, France ceded its North American possessions to Great Britain via the Treaty of Paris (1763), which was unambiguous and ended disputes over Acadia's boundaries. [40] The only territory France gained was Saint Pierre and Miquelon, intended as a refuge for its fishermen. [note 2] [18] [41]

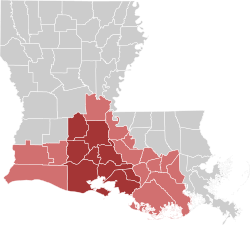

- Acadia's boundaries in 1754.

- Current boundaries of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

The St. Croix River and a line due north formed Nova Scotia's new boundary—the same as that of William Alexander's Nova Scotia in 1621. [34] The territory of Sagadahock thus defaulted to Massachusetts possession. [34]

All internal French-era boundaries in Acadia were dissolved. [36] Newfoundland was granted all coastline from the Saguenay River in the west to Hudson Strait in the north, including islands such as Anticosti and the Magdalen Islands. [18] Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean were annexed to Nova Scotia; Governor Montague Wilmot's commission defined their boundaries. [18] By expanding Nova Scotia, the British aimed to consolidate their presence and assert authority over continental Acadian territories claimed since the Treaty of Utrecht. [18]

The Province of Quebec, replacing Canada, was created later in 1763. [18] Its southern boundary ran along the 45th parallel north, then north along the highlands (the Appalachian Mountains) dividing the St. Lawrence River watershed from that of the Atlantic Ocean, and finally east along the north shore of the Chaleur Bay to Cap des Rosiers. [18] This deprived Quebec of the Gaspé Peninsula. [note 3] [42] The Quebec Act of 1774 confirmed this boundary but granted other lands, including those ceded to Newfoundland in 1763. [43] Unrest in the Thirteen Colonies prompted British expansion of Quebec's territory, but this decision contributed to the American Revolution. [43] The texts overlooked that the "highlands" do not approach Chaleur Bay in this manner and ignored the Restigouche River, which flows into the bay rather than the St. Lawrence or Atlantic, leaving part of the boundary undefined. [40] Contemporary maps depicted the Restigouche farther north and shorter than in reality, explaining the confusion. [40] Most cartographers resolved this by drawing a straight line east from the highlands to the Restigouche's mouth, while Des Barres' more accurate map diverted the boundary around the river's source and then followed the shortest path to Chaleur Bay. [40] In any case, Quebec's southern boundary automatically became the northern boundary of Massachusetts and Nova Scotia. [42]

- Quebec's boundaries in 1774.

- Satellite view of Chaleur Bay and Gaspé Peninsula.

Massachusetts continued claiming the territory of Sagadahock (lands east to the St. Croix River), while Nova Scotia claimed lands west to the Penobscot River as heir to Acadia. [42] However, the Treaty of Paris and Quebec Act transferred northern Sagadahock to Quebec. [42] Governor Wilmot's 1763 commission held that Nova Scotia's western boundary ran from Cape Sable through the Bay of Fundy to the St. Croix's mouth, then due north to Quebec's southern boundary. [42] This created a "north angle," frequently mentioned thereafter. [42] Notably, the commission stated Nova Scotia once extended to the Penobscot, a phrasing that avoided finality amid ongoing boundary disputes. [42]

Nova Scotia had been divided into counties in 1759, with all territory north of Kings County, Nova Scotia—including present-day New Brunswick—falling within Cumberland County, Nova Scotia. [36] The Saint John River valley was separated from Cumberland in 1765 to form Sunbury County. [36] A boundary between the counties was established in 1770. [36] Sunbury's western boundary was described as running due north from the St. Croix's source to the Saint John River, then to Quebec's southern boundary. [36] This overlapped part of present-day Maine, as reaching Quebec from the Saint John required veering far west near the Chaudière River's source. [36]

- Modern Cumberland County.

- Modern Sunbury County.

- Saint John River.

- Chaudière River.

Île Saint-Jean was nearly depopulated in 1758 during the Expulsion of the Acadians before being surveyed in 1764 and granted to various English lords in 1767. [43] At their request, the island was separated from Nova Scotia in 1769 and renamed Prince Edward Island in 1798. [43] New Brunswick was separated from Nova Scotia in 1784. [44] Île Royale, renamed Cape Breton Island, became a separate province in 1784 but was rejoined to Nova Scotia in 1820. [45]

Summary

Acadia

| Name [18] | Duration | Sovereignty | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acadia | 1604–1620 (1632 for the French) | Explorations of Giovanni da Verrazzano (1524) | |

| New England | 1620–1621 | Grant of the Plymouth Council for New England | |

| Nova Scotia | 1621–1632 | Grant to William Alexander | |

| Acadia | 1632–1654 (1664 for the French) | Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632) | |

| Nova Scotia | 1654–1667 | Invasion by Robert Sedgwick, Treaty of Westminster (1654) | |

| Acadia | 1667–1674 | Treaty of Breda (1667) | |

| New Holland | 1674–1678 | Invasion by Jurriaen Aernoutsz | |

| Acadia | 1678–1691 | Treaty of Nijmegen | |

| Massachusetts | 1691–1696 | Invasion by William Phips | |

| Nova Scotia | 1696–1697 | Separation from Massachusetts | |

| Acadia | 1697–1713 (1763 according to France) | Treaty of Ryswick | |

| Nova Scotia | 1713–present | Treaty of Utrecht |

Territory of Sagadahock

| Name [34] | Duration | Sovereignty | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Territory of Sagadahock | 1664–1667 | Grant by Charles II to the Duke of York | |

| Acadia | 1667–1674 | Treaty of Breda (1667) | |

| Territory of Sagadahock | 1674–1678 | Restoration of grant to the Duke of York | |

| Acadia | 1678–1691 | Treaty of Nijmegen | |

| Massachusetts | 1690–1691 | Invasion by William Phips | |

| Nova Scotia | 1691–1696 | Separation from Massachusetts | |

| Acadia | 1696–1713 | Treaty of Ryswick | |

| Territory of Sagadahock | 1713–1763 | Treaty of Utrecht | |

| Massachusetts | 1763–present | Treaty of Paris (1763) |

Partition of Acadia

| Name | Duration | Sovereignty | Origin | Portion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île Royale | 1713–1763 | Treaty of Utrecht | Gulf of St. Lawrence islands | |

| | Since 1713 | Treaty of Utrecht | Peninsular portion and later Île Royale/Cape Breton Island | |

| Territory of Sagadahock | 1713–1763 | Treaty of Utrecht | Portion west of St. Croix River | |

| | 1763–1820 | Treaty of Paris (1763) | Territory of Sagadahock | |

| | Since 1769 | Former Île Saint-Jean | ||

| Province of Quebec | 1774–1791 | Quebec Act | Gaspé, Magdalen Islands, north of Sagadahock territory | |

| | Since 1784 | Continental portion east of St. Croix River and south of Chaleur Bay | ||

| Cape Breton Island | 1784–1820 | Former Île Royale | ||

| Lower Canada | 1791–1841 | Constitutional Act 1791 | Gaspé, Magdalen Islands, north of Sagadahock territory | |

| | Since 1820 | Missouri Compromise | Territory of Sagadahock | |

| | 1841–1867 | Act of Union 1840 | Gaspé, Magdalen Islands, north of Sagadahock territory | |

| | Since 1867 | British North America Acts | Gaspé, Magdalen Islands, north of Sagadahock territory |