Salami slicing is a series of many small actions, often performed by clandestine means, that as an accumulated whole produces a much larger action or result that would be difficult or unlawful to perform all at once. The term is typically used pejoratively. An example of salami slicing, also known as penny shaving, is the fraudulent practice of stealing money repeatedly in extremely small quantities, usually by taking advantage of rounding to the nearest cent in financial transactions. It would be done by always rounding down, and putting the fractions of a cent into another account. The idea is to make the change small enough that any single transaction will go undetected. Coin-shaving apps are a legal example of this same logic. These apps automatically set aside small amounts of value from every financial transaction for subsequent investment or charity.

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has special rights regarding the exploration and use of marine resources, including energy production from water and wind. It stretches from the baseline out to 200 nautical miles (nmi) from the coast of the state in question. It is also referred to as a maritime continental margin and, in colloquial usage, may include the continental shelf. The term does not include either the territorial sea or the continental shelf beyond the 200 nautical mile limit. The difference between the territorial sea and the exclusive economic zone is that the first confers full sovereignty over the waters, whereas the second is merely a "sovereign right" which refers to the coastal state's rights below the surface of the sea. The surface waters, as can be seen in the map, are international waters.

China–India relations, also called Sino-Indian relations or Indo–Chinese relations, refers to the bilateral relationship between China and India. China and India had historically peaceful relations for thousands of years of recorded history. But the tone of the relationship has varied in modern time, especially after the rule of Communist Party in China; the two nations have sought economic cooperation with each other, while frequent border disputes and economic nationalism in both countries are a major point of contention. The modern relationship began in 1950 when India was among the first countries to end formal ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and recognise the People's Republic of China as the legitimate government of Mainland China. China and India are two of the major regional powers in Asia, and are the two most populous countries and among the fastest growing major economies in the world. Growth in diplomatic and economic influence has increased the significance of their bilateral relationship.

Over the last four thousand years, Chinese Imperialism has been a central feature of the history of East Asia. Since the recovery of Chinese strength in the late 20th century, the issues involved have been of concern to China's neighbors.

Salami tactics, also known as the salami-slice strategy or salami attacks, is a divide and conquer process of threats and alliances used to overcome opposition. With it, an aggressor can influence and eventually dominate a landscape, typically political, piece by piece. In this fashion, the opposition is eliminated "slice by slice" until it realizes, usually too late, that it is virtually gone in its entirety. In some cases it includes the creation of several factions within the opposing political party and then dismantling that party from the inside, without causing the 'sliced' sides to protest. Salami tactics are most likely to succeed when the perpetrators keep their true long-term motives hidden and maintain a posture of cooperativeness and helpfulness while engaged in the intended gradual subversion.

Freedom of navigation (FON) is a principle of customary international law that ships flying the flag of any sovereign state shall not suffer interference from other states, apart from the exceptions provided for in international law. In the realm of international law, it has been defined as “freedom of movement for vessels, freedom to enter ports and to make use of plant and docks, to load and unload goods and to transport goods and passengers". This right is now also codified as Article 87(1)a of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Not all UN member states have ratified the convention; notably, the United States has not signed nor ratified the convention. However, the § United States enforces the practice; see below.

The String of Pearls is a geopolitical hypothesis proposed by United States political researchers in 2004. The term refers to the network of Chinese military and commercial facilities and relationships along its sea lines of communication, which extend from the Chinese mainland to Port Sudan in the Horn of Africa. The sea lines run through several major maritime choke points such as the Strait of Mandeb, the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Lombok Strait as well as other strategic maritime centres in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Somalia.

General Bipin Rawat, is a four star general of the Indian Army. He is the first and current Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) of India. On 30 December 2019, he was appointed as the first CDS of India and assumed office from 1 January 2020. Prior to taking over as the CDS, he served as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee as well as 26th Chief of Army Staff of the Indian Army.

The nine-dash line—at various times also referred to as the ten-dash line and the eleven-dash line—refers to the ill-defined demarcation line used by the People's Republic of China (China) and the Republic of China (Taiwan), for their claims of the major part of the South China Sea. The contested area in the South China Sea includes the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands, and various other areas including Pratas Island and the Vereker Banks, the Macclesfield Bank and the Scarborough Shoal. The claim encompasses the area of Chinese land reclamation known as the "Great Wall of Sand". Despite having made the vague claim public in 1947, neither the PRC nor the ROC has filed a formal and specifically defined claim to the area.

The South China Sea disputes involve both island and maritime claims by several sovereign states within the region, namely Brunei, the People's Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. An estimated US$3.37 trillion worth of global trade passes through the South China Sea annually, which accounts for a third of the global maritime trade. 80 percent of China's energy imports and 39.5 percent of China's total trade passes through the South China Sea.

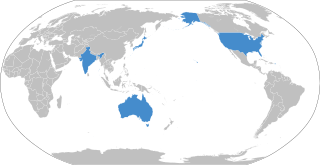

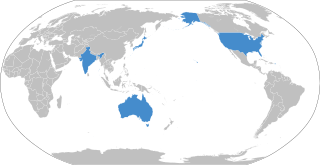

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue is a strategic dialogue between the United States, Japan, Australia and India that is maintained by talks between member countries. The dialogue was initiated in 2007 by the then Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe, with the support of the then Vice President of USA Dick Cheney, the then Prime Minister of Australia John Howard and the then Prime Minister of India Manmohan Singh. The dialogue was paralleled by joint military exercises of an unprecedented scale, titled Exercise Malabar. The diplomatic and military arrangement was widely viewed as a response to increased Chinese economic and military power, and the Chinese government responded to the Quadrilateral dialogue by issuing formal diplomatic protests to its members.

The first island chain refers to the first chain of major archipelagos out from the East Asian continental mainland coast. It is principally composed of the Kuril Islands, the Japanese Archipelago, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan (Formosa), the northern Philippines, and Borneo, hence extending all the way from the Kamchatka Peninsula in the northeast to the Malay Peninsula in the southwest. Some definitions of the first island chain anchor the northern end on the Russian Far East coast north of Sakhalin Island, with Sakhalin Island being the first link in the chain. However, others consider the Aleutians as the farthest north-eastern first link in the chain. The first island chain forms one of three island chain doctrines within the Island Chain Strategy in US foreign policy.

The East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone is an Air Defense Identification Zone covering most of the East China Sea where the People's Republic of China announced that it was introducing new air traffic restrictions in November 2013. The area consists of the airspace from about, and including, the Japanese controlled Senkaku Islands north to South Korean-claimed Socotra Rock. About half of the area overlaps with a Japanese ADIZ, while also overlapping to a small extent with the South Korean and Taiwanese ADIZ. When introduced the Chinese initiative drew criticism as the ADIZ overlapped with the ADIZ of other countries, imposed requirements on both civilian and military aircraft regardless of destination, and included contested maritime areas

The Belt and Road Initiative, known in Chinese and formerly in English as One Belt One Road or OBOR for short, is a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013 to invest in nearly 70 countries and international organizations. It is considered a centerpiece of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary and Chinese leader Xi Jinping's foreign policy, who originally announced the strategy as the "Silk Road Economic Belt" during an official visit to Kazakhstan in September 2013.

Debt-trap diplomacy is a theory that describes a powerful lending country or institution seeking to saddle a borrowing nation with enormous debt so as to increase its leverage over it. Debt-trap diplomacy was associated with Indian academic Brahma Chellaney, who promoted the term in early 2017. It has been used contentiously in relation to Chinese state-backed lending policies to other countries.

The People's Republic of China is a Communist state that came to power in 1949 after a civil war. It became a great power in the 1960s and today has the world's largest population, second largest GDP and the largest economy in the world by PPP. China is now considered an emerging global superpower. The main institutions of foreign policy are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party, and the United Front Work Department.

Brahma Chellaney is a New Delhi-based geostrategist and author who won the Asia Society's 2012 Bernard Schwartz Book Award. He is a columnist for Project Syndicate. He "commands respect", as one magazine put it, for his independent scholarship and for speaking truth to power. He received the $20,000 Bernard Schwartz Award from the New York-based Asia Society for his work, Water: Asia's New Battleground, published by Georgetown University Press.

The Five Fingers of Tibet is a Chinese foreign policy attributed to Mao Zedong that considers Tibet to be China's right hand palm, with five fingers on its periphery: Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh, and that it is China's responsibility to "liberate" these regions. It was never discussed in official Chinese public statements, but external concerns have been raised over its possible continued existence or revival. An article in a provincial mouthpiece magazine of the Chinese Communist Party verified the existence of this policy in the aftermath of the 2017 China–India border standoff.

The People's Armed Forces Maritime Militia is the government funded maritime militia of China. For reportedly operating in the South China Sea without clear identification, they are sometimes referred to as the "little blue men", a term coined by Andrew S. Erickson of the Naval War College in reference to Russia's "little green men" during the 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Cabbage tactics is a militarily swarming and overwhelming tactic of seizing control of islands. It is a tactic to overwhelm and seize control of an island by surrounding and wrapping the island in successive layers of Chinese naval ships, China Coast Guard ships and fishing boats and cut-off the island from outside support.