Related Research Articles

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution, patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

A randomized controlled trial is a form of scientific experiment used to control factors not under direct experimental control. Examples of RCTs are clinical trials that compare the effects of drugs, surgical techniques, medical devices, diagnostic procedures, diets or other medical treatments.

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of deaths per 1,000 individuals per year; thus, a mortality rate of 9.5 in a population of 1,000 would mean 9.5 deaths per year in that entire population, or 0.95% out of the total. It is distinct from "morbidity", which is either the prevalence or incidence of a disease, and also from the incidence rate.

A cohort study is a particular form of longitudinal study that samples a cohort, performing a cross-section at intervals through time. It is a type of panel study where the individuals in the panel share a common characteristic.

A case–control study is a type of observational study in which two existing groups differing in outcome are identified and compared on the basis of some supposed causal attribute. Case–control studies are often used to identify factors that may contribute to a medical condition by comparing subjects who have the condition with patients who do not have the condition but are otherwise similar. They require fewer resources but provide less evidence for causal inference than a randomized controlled trial. A case–control study is often used to produce an odds ratio. Some statistical methods make it possible to use a case–control study to also estimate relative risk, risk differences, and other quantities.

A cancer cluster is a disease cluster in which a high number of cancer cases occurs in a group of people in a particular geographic area over a limited period of time.

Infection prevention and control is the discipline concerned with preventing healthcare-associated infections; a practical rather than academic sub-discipline of epidemiology. In Northern Europe, infection prevention and control is expanded from healthcare into a component in public health, known as "infection protection". It is an essential part of the infrastructure of health care. Infection control and hospital epidemiology are akin to public health practice, practiced within the confines of a particular health-care delivery system rather than directed at society as a whole.

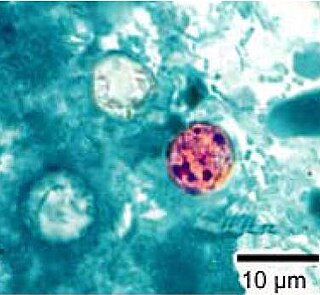

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a coccidian parasite that causes a diarrheal disease called cyclosporiasis in humans and possibly in other primates. Originally reported as a novel pathogen of probable coccidian nature in the 1980s and described in the early 1990s, it was virtually unknown in developed countries until awareness increased due to several outbreaks linked with fecally contaminated imported produce. C. cayetanensis has since emerged as an endemic cause of diarrheal disease in tropical countries and a cause of traveler's diarrhea and food-borne infections in developed nations. This species was placed in the genus Cyclospora because of the spherical shape of its sporocysts. The specific name refers to the Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru, where early epidemiological and taxonomic work was done.

Ralph S. Paffenbarger, Jr. was an epidemiologist, ultramarathoner, and professor at both Stanford University School of Medicine and Harvard University School of Public Health.

Meningococcal disease describes infections caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. It has a high mortality rate if untreated but is vaccine-preventable. While best known as a cause of meningitis, it can also result in sepsis, which is an even more damaging and dangerous condition. Meningitis and meningococcemia are major causes of illness, death, and disability in both developed and under-developed countries.

A hierarchy of evidence, comprising levels of evidence (LOEs), that is, evidence levels (ELs), is a heuristic used to rank the relative strength of results obtained from experimental research, especially medical research. There is broad agreement on the relative strength of large-scale, epidemiological studies. More than 80 different hierarchies have been proposed for assessing medical evidence. The design of the study and the endpoints measured affect the strength of the evidence. In clinical research, the best evidence for treatment efficacy is mainly from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Systematic reviews of completed, high-quality randomized controlled trials – such as those published by the Cochrane Collaboration – rank the same as systematic review of completed high-quality observational studies in regard to the study of side effects. Evidence hierarchies are often applied in evidence-based practices and are integral to evidence-based medicine (EBM).

A notifiable disease is any disease that is required by law to be reported to government authorities. The collation of information allows the authorities to monitor the disease, and provides early warning of possible outbreaks. In the case of livestock diseases, there may also be the legal requirement to kill the infected livestock upon notification. Many governments have enacted regulations for reporting of both human and animal diseases.

In epidemiology, a clinical case definition, a clinical definition, or simply a case definition lists the clinical criteria by which public health professionals determine whether a person's illness is included as a case in an outbreak investigation—that is, whether a person is considered directly affected by an outbreak. Absent an outbreak, case definitions are used in the surveillance of public health in order to categorize those conditions present in a population.

H5N1 influenza virus is a type of influenza A virus which mostly infects birds. H5N1 flu is a concern due to the its global spread that may constitute a pandemic threat. The yardstick for human mortality from H5N1 is the case-fatality rate (CFR); the ratio of the number of confirmed human deaths resulting from infection of H5N1 to the number of those confirmed cases of infection with the virus. For example, if there are 100 confirmed cases of a disease and 50 die as a consequence, then the CFR is 50%. The case fatality rate does not take into account cases of a disease which are unconfirmed or undiagnosed, perhaps because symptoms were mild and unremarkable or because of a lack of diagnostic facilities. The Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) is adjusted to allow for undiagnosed cases.

The Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System (WBDOSS) is a national surveillance system maintained by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The WBDOSS receives data about waterborne disease outbreaks and single cases of waterborne diseases of public health importance in the United States and then disseminates information about these diseases, outbreaks, and their causes. WBDOSS was initiated in 1971 by CDC, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Data are reported by public health departments in individual states, territories, and the Freely Associated States. Although initially designed to collect data about drinking water outbreaks in the United States, WBDOSS now includes outbreaks associated with recreational water, as well as outbreaks associated with water that is not intended for drinking (non-recreational) and water for which the intended use is unknown.

The 1983 West Bank fainting epidemic occurred in late March and early April 1983. Researchers point to mass hysteria as the most likely explanation. Large numbers of Palestinians complained of fainting and dizziness, the vast majority of whom were teenage girls with a smaller number of female Israeli soldiers in multiple West Bank towns, leading to 943 hospitalizations.

A superspreading event (SSEV) is an event in which an infectious disease is spread much more than usual, while an unusually contagious organism infected with a disease is known as a superspreader. In the context of a human-borne illness, a superspreader is an individual who is more likely to infect others, compared with a typical infected person. Such superspreaders are of particular concern in epidemiology.

The discipline of forensic epidemiology (FE) is a hybrid of principles and practices common to both forensic medicine and epidemiology. FE is directed at filling the gap between clinical judgment and epidemiologic data for determinations of causality in civil lawsuits and criminal prosecution and defense.

The Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP) is a nationwide disease surveillance system in India incorporating both the state and central governments aimed at early detection and long term monitoring of diseases for enabling efficient policy decisions. It was started in 2004 with the assistance of the World Bank. A central surveillance unit has been set up at the National Centre for Disease Control in Delhi. All states, union territories, and district headquarters of India have established surveillance units. Weekly data is submitted from over 90% of the 741 districts in the country. With the aim of improving digital surveillance capabilities, the Integrated Health Information Platform (IHIP) was launched in a number of states in November 2019.

SaTScan is a software tool that employs scan statistics for the spatial and temporal analysis of clusters of events. The software is trademarked by Martin Kulldorff, and was designed originally for public health and epidemiology to identify clusters of cases in both space and time and to perform statistical analysis to determine if these clusters are significantly different from what would be expected by chance The software provides a user-friendly interface and a range of statistical methods, making it accessible to researchers and practitioners. While not a full Geographic Information System, the outputs from SaTScan can be integrated with software such as ArcGIS or QGIS to visualize and analyze spatial data, and to map the distribution of various phenomena.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Miquel Porta, ed. (2008). A Dictionary of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-19-971815-3.

Aggregations of relatively uncommon events or diseases in space and/or time in amounts that are believed or perceived to be greater than could be expected by chance. Putative disease clusters are often perceived to exist on the basis of anecdotal evidence, and much effort may be expended by epidemiologists and biostatisticians in assessing whether a true cluster of disease exists.

- ↑ "Guidelines for Investigating Clusters of Health Events". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.