Related Research Articles

The term abdominal surgery broadly covers surgical procedures that involve opening the abdomen (laparotomy). Surgery of each abdominal organ is dealt with separately in connection with the description of that organ Diseases affecting the abdominal cavity are dealt with generally under their own names.

Surgery is a medical specialty that uses manual and instrumental techniques to diagnose or treat pathological conditions, to alter bodily functions, to reconstruct or improve aesthetics and appearance, or to remove unwanted tissues or foreign bodies.

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. In 2011, cholecystectomy was the eighth most common operating room procedure performed in hospitals in the United States. Cholecystectomy can be performed either laparoscopically, or via an open surgical technique.

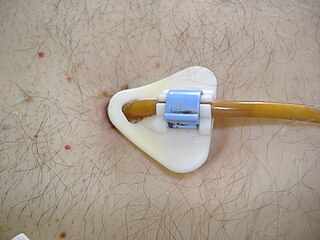

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is an endoscopic medical procedure in which a tube is passed into a patient's stomach through the abdominal wall, most commonly to provide a means of feeding when oral intake is not adequate. This provides enteral nutrition despite bypassing the mouth; enteral nutrition is generally preferable to parenteral nutrition. The PEG procedure is an alternative to open surgical gastrostomy insertion, and does not require a general anesthetic; mild sedation is typically used. PEG tubes may also be extended into the small intestine by passing a jejunal extension tube through the PEG tube and into the jejunum via the pylorus.

Perioperative mortality has been defined as any death, regardless of cause, occurring within 30 days after surgery in or out of the hospital. Globally, 4.2 million people are estimated to die within 30 days of surgery each year. An important consideration in the decision to perform any surgical procedure is to weigh the benefits against the risks. Anesthesiologists and surgeons employ various methods in assessing whether a patient is in optimal condition from a medical standpoint prior to undertaking surgery, and various statistical tools are available. ASA score is the most well known of these.

Colectomy is the surgical removal of any extent of the colon, the longest portion of the large bowel. Colectomy may be performed for prophylactic, curative, or palliative reasons. Indications include cancer, infection, infarction, perforation, and impaired function of the colon. Colectomy may be performed open, laparoscopically, or robotically. Following removal of the bowel segment, the surgeon may restore continuity of the bowel or create a colostomy. Partial or subtotal colectomy refers to removing a portion of the colon, while total colectomy involves the removal of the entire colon. Complications of colectomy include anastomotic leak, bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding structures.

Bone grafting is a surgical procedure that replaces missing bone in order to repair bone fractures that are extremely complex, pose a significant health risk to the patient, or fail to heal properly. Some small or acute fractures can be cured without bone grafting, but the risk is greater for large fractures like compound fractures.

A dental extraction is the removal of teeth from the dental alveolus (socket) in the alveolar bone. Extractions are performed for a wide variety of reasons, but most commonly to remove teeth which have become unrestorable through tooth decay, periodontal disease, or dental trauma, especially when they are associated with toothache. Sometimes impacted wisdom teeth cause recurrent infections of the gum (pericoronitis), and may be removed when other conservative treatments have failed. In orthodontics, if the teeth are crowded, healthy teeth may be extracted to create space so the rest of the teeth can be straightened.

Knee replacement, also known as knee arthroplasty, is a surgical procedure to replace the weight-bearing surfaces of the knee joint to relieve pain and disability, most commonly offered when joint pain is not diminished by conservative sources. It may also be performed for other knee diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. In patients with severe deformity from advanced rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, or long-standing osteoarthritis, the surgery may be more complicated and carry higher risk. Osteoporosis does not typically cause knee pain, deformity, or inflammation, and is not a reason to perform knee replacement.

Antibiotic prophylaxis refers to, for humans, the prevention of infection complications using antimicrobial therapy. Antibiotic prophylaxis in domestic animal feed mixes has been employed in America since at least 1970.

Spinal fusion, also called spondylodesis or spondylosyndesis, is a surgery performed by orthopaedic surgeons or neurosurgeons that joins two or more vertebrae. This procedure can be performed at any level in the spine and prevents any movement between the fused vertebrae. There are many types of spinal fusion and each technique involves using bone grafting—either from the patient (autograft), donor (allograft), or artificial bone substitutes—to help the bones heal together. Additional hardware is often used to hold the bones in place while the graft fuses the two vertebrae together. The placement of hardware can be guided by fluoroscopy, navigation systems, or robotics.

An incisional hernia is a type of hernia caused by an incompletely-healed surgical wound. Since median incisions in the abdomen are frequent for abdominal exploratory surgery, ventral incisional hernias are often also classified as ventral hernias due to their location. Not all ventral hernias are from incisions, as some may be caused by other trauma or congenital problems.

Failed Back Syndrome is a condition characterized by chronic pain following back surgeries. The term "post-laminectomy syndrome" is sometimes used by doctors to indicate the same condition as failed back syndrome. Many factors can contribute to the onset or development of FBS, including residual or recurrent spinal disc herniation, persistent post-operative pressure on a spinal nerve, altered joint mobility, joint hypermobility with instability, scar tissue (fibrosis), depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, spinal muscular deconditioning and Cutibacterium acnes infection. An individual may be predisposed to the development of FBS due to systemic disorders such as diabetes, autoimmune disease and peripheral blood vessels (vascular) disease.

Endophthalmitis, or endophthalmia, is inflammation of the interior cavity of the eye, usually caused by an infection. It is a possible complication of all intraocular surgeries, particularly cataract surgery, and can result in loss of vision or loss of the eye itself. Infection can be caused by bacteria or fungi, and is classified as exogenous, or endogenous. Other non-infectious causes include toxins, allergic reactions, and retained intraocular foreign bodies. Intravitreal injections are a rare cause, with an incidence rate usually less than 0.05%.

An open fracture, also called a compound fracture, is a type of bone fracture that has an open wound in the skin near the fractured bone. The skin wound is usually caused by the bone breaking through the surface of the skin. An open fracture can be life threatening or limb-threatening due to the risk of a deep infection and/or bleeding. Open fractures are often caused by high energy trauma such as road traffic accidents and are associated with a high degree of damage to the bone and nearby soft tissue. Other potential complications include nerve damage or impaired bone healing, including malunion or nonunion. The severity of open fractures can vary. For diagnosing and classifying open fractures, Gustilo-Anderson open fracture classification is the most commonly used method. This classification system can also be used to guide treatment, and to predict clinical outcomes. Advanced trauma life support is the first line of action in dealing with open fractures and to rule out other life-threatening condition in cases of trauma. The person is also administered antibiotics for at least 24 hours to reduce the risk of an infection.

Breast surgery is a form of surgery performed on the breast.

Vaginal evisceration is an evisceration of the small intestine that occurs through the vagina, typically subsequent to vaginal hysterectomy, and following sexual intercourse after the surgery. It is a surgical emergency.

Alloplasty is a surgical procedure performed to substitute and repair defects within the body with the use of synthetic material. It can also be performed in order to bridge wounds. The process of undergoing alloplasty involves the construction of an alloplastic graft through the use of computed tomography (CT), rapid prototyping and "the use of computer-assisted virtual model surgery." Each alloplastic graft is individually constructed and customised according to the patient's defect to address their personal health issue. Alloplasty can be applied in the form of reconstructive surgery. An example where alloplasty is applied in reconstructive surgery is in aiding cranial defects. The insertion and fixation of alloplastic implants can also be applied in cosmetic enhancement and augmentation. Since the inception of alloplasty, it has been proposed that it could be a viable alternative to other forms of transplants. The biocompatibility and customisation of alloplastic implants and grafts provides a method that may be suitable for both minor and major medical cases that may have more limitations in surgical approach. Although there has been evidence that alloplasty is a viable method for repairing and substituting defects, there are disadvantages including suitability of patient bone quality and quantity for long term implant stability, possibility of rejection of the alloplastic implant, injuring surrounding nerves, cost of procedure and long recovery times. Complications can also occur from inadequate engineering of alloplastic implants and grafts, and poor implant fixation to bone. These include infection, inflammatory reactions, the fracture of alloplastic implants and prostheses, loosening of implants or reduced or complete loss of osseointegration.

Transvaginal mesh, also known as vaginal mesh implant, is a net-like surgical tool that is used to treat pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) among female patients. The surgical mesh is placed transvaginally to reconstruct weakened pelvic muscle walls and to support the urethra or bladder.

A surgical site infection (SSI) develop when bacteria infiltrate the body through surgical incisions. These bacteria may come from the patient's own skin, the surgical instruments, or the environment in which the procedure is performed.

References

- ↑ Stadelmann WK, Digenis AG, Tobin GR (August 1998). "Physiology and healing dynamics of chronic cutaneous wounds". American Journal of Surgery. 176 (2A Suppl): 26S–38S. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00183-4. PMID 9777970.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hoffman B (2012). Williams gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 972–975. ISBN 9780071716727.

- ↑ Stanirowski PJ, Wnuk A, Cendrowski K, Sawicki W (October 2015). "Growth factors, silver dressings and negative pressure wound therapy in the management of hard-to-heal postoperative wounds in obstetrics and gynecology: a review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 292 (4): 757–775. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3709-y. PMC 4560760 . PMID 25864095.

- ↑ Pahys JM, Pahys JR, Cho SK, Kang MM, Zebala LP, Hawasli AH, et al. (March 2013). "Methods to decrease postoperative infections following posterior cervical spine surgery". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 95 (6): 549–554. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00756. PMID 23515990. S2CID 207283208.

- 1 2 3 "Surgical wound infection - treatment". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Kelkar A, Agarwal AG, Jayaswal D, Schultz C, Jayaswal A, et al. (August 2020). "Implant Retention or Removal for Management of Surgical Site Infection After Spinal Surgery". Global Spine Journal. 10 (5): 640–646. doi:10.1177/2192568219869330. PMC 7359681 . PMID 32677561.

- ↑ "The Hardest Decision Any Spine Surgeon Has to Make | Orthopedics This Week". ryortho.com. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ↑ World Health Organization WHO. "WHO Surgical Site infection Prevention Guidelines Web Appendix 25" (PDF). Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ Espin Basany E, Solís-Peña A, Pellino G, Kreisler E, Fraccalvieri D, Muinelo-Lorenzo M, et al. (August 2020). "Preoperative oral antibiotics and surgical-site infections in colon surgery (ORALEV): a multicentre, single-blind, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 5 (8): 729–738. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30075-3. PMID 32325012. S2CID 216109202.

- 1 2 Pellino G, Espín-Basany E (December 2021). "Bowel decontamination before colonic and rectal surgery". The British Journal of Surgery. 109 (1): 3–7. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab389 . PMID 34849592.

- ↑ Nelson RL, Hassan M, Grant MD (December 2020). "Antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery: are oral, intravenous or both best and is mechanical bowel preparation necessary?". Techniques in Coloproctology. 24 (12): 1233–1246. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02301-x. PMID 32734477. S2CID 220857409.

- ↑ Koskenvuo L, Lehtonen T, Koskensalo S, Rasilainen S, Klintrup K, Ehrlich A, et al. (September 2019). "Mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation for elective colectomy (MOBILE): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, single-blinded trial". Lancet. 394 (10201): 840–848. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31269-3. hdl: 10138/319567 . PMID 31402112. S2CID 199540216.

- ↑ Edmiston CE, Seabrook GR, Goheen MP, Krepel CJ, Johnson CP, Lewis BD, et al. (October 2006). "Bacterial adherence to surgical sutures: can antibacterial-coated sutures reduce the risk of microbial contamination?". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 203 (4): 481–489. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.06.026. PMID 17000391.

- ↑ Shahpari O, Mousavian A, Elahpour N, Malahias MA, Ebrahimzadeh MH, Moradi A (January 2020). "The Use of Antibiotic Impregnated Cement Spacers in the Treatment of Infected Total Joint Replacement: Challenges and Achievements". The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 8 (1): 11–20. doi:10.22038/abjs.2019.42018.2141. PMC 7007713 . PMID 32090140.

- ↑ McHugh SM, Collins CJ, Corrigan MA, Hill AD, Humphreys H (April 2011). "The role of topical antibiotics used as prophylaxis in surgical site infection prevention". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 66 (4): 693–701. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr009 . PMID 21393223.

- ↑ Kachel E, Moshkovitz Y, Sternik L, Sahar G, Grosman-Rimon L, Belotserkovsky O, et al. (October 2020). "Local prolonged release of antibiotic for prevention of sternal wound infections postcardiac surgery-A novel technology". Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 35 (10): 2695–2703. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14890 . PMID 32743813. S2CID 220940129.

- 1 2 Ademuyiwa, Adesoji O.; et al. (November 2021). "Reducing surgical site infections in low-income and middle-income countries (FALCON): a pragmatic, multicentre, stratified, randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 398 (10312): 1687–1699. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01548-8. PMC 8586736 . PMID 34710362.

- ↑ Liu Z, Dumville JC, Norman G, Westby MJ, Blazeby J, McFarlane E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (February 2018). "Intraoperative interventions for preventing surgical site infection: an overview of Cochrane Reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (2): CD012653. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012653.pub2. PMC 6491077 . PMID 29406579.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Lin B, Agarwal AG, Elgafy H, Schultz C, Agarwal AK, et al. (October 2020). "A Multicenter Trial Demonstrating Presence or Absence of Bacterial Contamination at the Screw-Bone Interface Owing to Absence or Presence of Pedicle Screw Guard, Respectively, During Spinal Fusion". Clinical Spine Surgery. 33 (8): E364–E368. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000976. PMID 32168115. S2CID 212707844.

- ↑ Agarwal A, MacMillan A, Goel V, Agarwal AK, Karas C (August 2018). "A Paradigm Shift Toward Terminally Sterilized Devices". Clinical Spine Surgery. 31 (7): 308–311. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000675. PMID 29912733. S2CID 49303554.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Schultz C, Agarwal AK, Wang JC, Garfin SR, Anand N (April 2019). "Harboring Contaminants in Repeatedly Reprocessed Pedicle Screws". Global Spine Journal. 9 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1177/2192568218784298. PMC 6448207 . PMID 30984497.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Schultz C, Goel VK, Agarwal A, Anand N, Garfin SR, Wang JC (October 2018). "Implant Prophylaxis: The Next Best Practice Toward Asepsis in Spine Surgery". Global Spine Journal. 8 (7): 761–765. doi:10.1177/2192568218762380. PMC 6232723 . PMID 30443488.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Lin B, Elgafy H, Goel V, Karas C, Schultz C, et al. (2020). "Updates on Evidence-Based Practices to Reduce Preoperative and Intraoperative Contamination of Implants in Spine Surgery: A Narrative Review". Spine Surgery and Related Research. 4 (2): 111–116. doi:10.22603/ssrr.2019-0038. PMC 7217678 . PMID 32405555.

- ↑ Agarwal A, Lin B, Wang JC, Schultz C, Garfin SR, Goel VK, et al. (February 2019). "Efficacy of Intraoperative Implant Prophylaxis in Reducing Intraoperative Microbial Contamination". Global Spine Journal. 9 (1): 62–66. doi: 10.1177/2192568218780676 . PMC 6362554 . PMID 30775210.

- ↑ "Ban 'Reprocessing' of Spinal Surgery Screws, Experts Say". Medscape. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ↑ Xiong, Ze; Achavananthadith, Sippanat; Lian, Sophie; Madden, Leigh Edward; Ong, Zi Xin; Chua, Wisely; Kalidasan, Viveka; Li, Zhipeng; Liu, Zhu; Singh, Priti; Yang, Haitao (November 2021). "A wireless and battery-free wound infection sensor based on DNA hydrogel". Science Advances. 7 (47): eabj1617. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abj1617. PMC 8604401 . PMID 34797719.

- ↑ Wood C, Phillips C, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2016). "Cyanoacrylate microbial sealants for skin preparation prior to surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD008062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008062.pub4. PMC 9308063 . PMID 27191948.

- ↑ Tanner J, Dumville JC, Norman G, Fortnam M, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (January 2016). "Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD004288. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004288.pub3. PMC 8647968 . PMID 26799160.

- ↑ Webster J, Alghamdi A, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (April 2015). "Use of plastic adhesive drapes during surgery for preventing surgical site infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD006353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006353.pub4. PMC 6575154 . PMID 25901509.