Ross Robert Barnett was an American politician and segregationist who served as the 53rd governor of Mississippi from 1960 to 1964. He was a Southern Democrat who supported racial segregation.

George Corley Wallace Jr. was the 45th governor of Alabama, serving from 1963 to 1967, again from 1971 to 1979, and finally from 1983 to 1987. He is remembered for his staunch segregationist and populist views, however, in the late 1970s, Wallace moderated his views on race, renouncing his support for segregation. During Wallace's tenure as governor of Alabama, he promoted "industrial development, low taxes, and trade schools." Wallace unsuccessfully sought the United States presidency as a Democratic Party candidate three times, and once as an American Independent Party candidate, carrying five states in the 1968 election. Wallace opposed desegregation and supported the policies of "Jim Crow" during the Civil Rights Movement, declaring in his infamous 1963 inaugural address that he stood for "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever".

James Alexander Hood was one of the first African Americans to enroll at the University of Alabama in 1963, and was made famous when Alabama Governor George Wallace attempted to block him and fellow student Vivian Malone from enrolling at the then all-white university, an incident which became known as the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door".

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression; they were part of a broader voting rights movement underway in Selma and throughout the American South. By highlighting racial injustice, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the civil rights movement.

Carl Edward Sanders Sr. was an American attorney and politician who served as the 74th governor of Georgia from 1963 to 1967.

Asa Earl Carter was a 1950s segregationist political activist, Ku Klux Klan organizer, and later Western novelist. He co-wrote George Wallace's well-known pro-segregation line of 1963, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever", and ran in the Democratic primary for governor of Alabama on a white supremacist ticket. Years later, under the pseudonym of supposedly Cherokee writer Forrest Carter, he wrote The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales (1972), a Western novel that was adapted into a 1976 film featuring Clint Eastwood that added to the National Film Registry, and The Education of Little Tree (1976), a best-selling, award-winning book which was marketed as a memoir but which turned out to be fiction.

John Malcolm Patterson was an American politician. He served one term as Attorney General of Alabama from 1955 to 1959, and, at age 37, served one term as the 44th Governor of Alabama from 1959 to 1963.

Frank Minis Johnson Jr. was a United States district judge and United States circuit judge serving 1955 to 1999 on the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama, United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. He made landmark civil rights rulings that helped end segregation and disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South. In the words of journalist and historian Bill Moyers, Judge Johnson "altered forever the face of the South."

The rule of three is a writing principle which suggests that a trio of entities such as events or characters is more humorous, satisfying, or effective than other numbers. The audience of this form of text is also thereby more likely to remember the information conveyed because having three entities combines both brevity and rhythm with having the smallest amount of information to create a pattern.

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama.

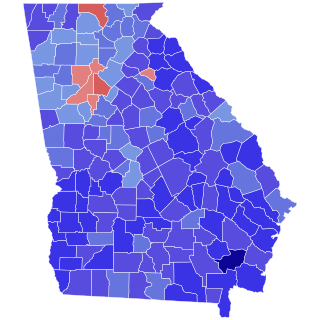

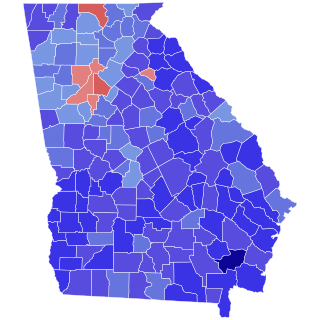

The 1970 Georgia gubernatorial election was held on November 3, 1970. It was marked by the election as Governor of Georgia of the relatively little-known former state senator Jimmy Carter after a hard battle in the Democratic primary. This election is famous because Carter, who was often regarded as one of the New South Governors, later ran for president in 1976 on his gubernatorial record and won. As of 2025, this was the last time Fulton County was carried by the Republican candidate in a gubernatorial election, the only time it failed to back Carter, and the last time a Democrat in any race won without carrying it. It is also the last time that Clarke County voted for the Republican candidate for governor.

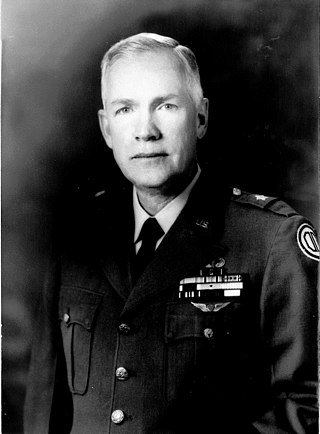

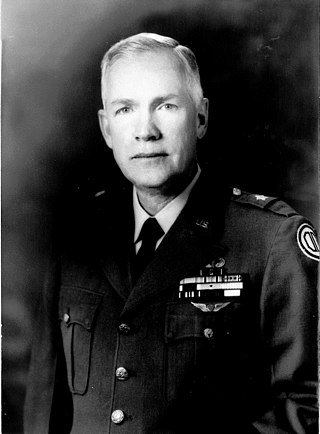

Henry Vance Graham was an American Army National Guard general who protected black activists during the civil rights movement. He is most famous for asking Alabama governor George Wallace to step aside and permit black students to register for classes at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa in 1963 during the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door" incident.

The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door took place at Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. In a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" and stop the desegregation of schools, George Wallace, the Democratic Governor of Alabama, stood at the door of the auditorium as if to block the way of the two African American students attempting to enter: Vivian Malone and James Hood.

Milton Louis Grafman was an American rabbi who led Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, Alabama, from 1941 until his retirement in 1975 and then served as Rabbi Emeritus from 1975 until his death in 1995. He was one of eight local clergy members who signed a public statement criticizing the Birmingham Campaign, to which Martin Luther King Jr. responded in his Letter from Birmingham Jail.

The Report to the American People on Civil Rights was a speech on civil rights, delivered on radio and television by United States President John F. Kennedy from the Oval Office on June 11, 1963, in which he proposed legislation that would later become the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Expressing civil rights as a moral issue, Kennedy moved past his previous appeals to legality and asserted that the pursuit of racial equality was a just cause. The address signified a shift in his administration's policy towards strong support of the civil rights movement and played a significant role in shaping his legacy as a proponent of civil rights.

Albert J. Lingo was appointed in 1963 by Alabama Gov. George Wallace to head the Alabama Highway Patrol, which he led until 1965 during turbulent years marked by marches and demonstrations that characterized the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. South.

The Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy was a Klan faction led by Asa Carter in the late 1950s. Despite the group's brief lifespan, it left its mark with a violent record, including an assault on Nat King Cole, participation in a riot in Clinton, Tennessee, and one of the few documented cases of castration by the Klan.

In the United States, school integration is the process of ending race-based segregation within American public and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and remains an issue in contemporary education. During the Civil Rights Movement school integration became a priority, but since then de facto segregation has again become prevalent.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

The 1967 Mississippi gubernatorial election took place on November 7, 1967, in order to elect the Governor of Mississippi. Incumbent Democrat Paul B. Johnson Jr. was term-limited, and could not run for reelection to a second term.