| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

| |

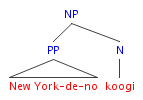

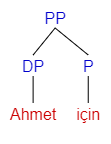

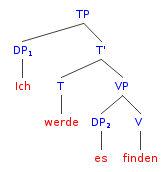

In linguistics, head directionality is a proposed parameter that classifies languages according to whether they are head-initial (the head of a phrase precedes its complements) or head-final (the head follows its complements). The head is the element that determines the category of a phrase: for example, in a verb phrase, the head is a verb. Therefore, head initial would be "VO" languages and head final would be "OV" languages. [1]

Contents

- Types of phrase

- Head-initial languages

- English

- Indonesian

- Head-final languages

- Japanese

- Turkish

- Mixed word-order languages

- German

- Chinese

- Gbe

- Theoretical views

- Dependency grammar

- Typology

- Fundamental Principle of Placement

- Principles and parameters

- Antisymmetry

- Gradient classification

- See also

- Notes

- Bibliography

Some languages are consistently head-initial or head-final at all phrasal levels. English is considered to be mainly head-initial (verbs precede their objects, for example), while Japanese is an example of a language that is consistently head-final. In certain other languages, such as German and Gbe, examples of both types of head directionality occur. Various theories have been proposed to explain such variation.

Head directionality is connected with the type of branching that predominates in a language: head-initial structures are right-branching, while head-final structures are left-branching. [2] On the basis of these criteria, languages can be divided into head-final (rigid and non-rigid) and head-initial types. The identification of headedness is based on the following: [3]

- the order of subject, object, and verb

- the relationship between the order of the object and verb

- the order of an adposition and its complement

- the order of relative clause and head noun.