Academic study

Missionary Robert Henry Codrington traveled widely in Melanesia, publishing several studies of its language and culture. His 1891 book The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folk-Lore contains the first detailed description of mana in English. [9] Codrington defines it as "a force altogether distinct from physical power, which acts in all kinds of ways for good and evil, and which it is of the greatest advantage to possess or control". [4]

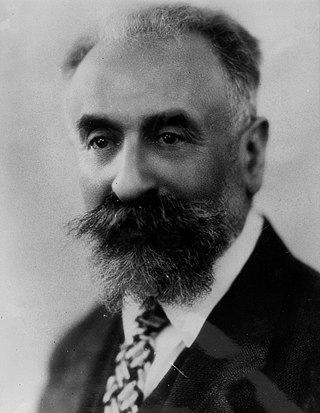

His era had already defined animism, the concept that the energy (or life) in an object derives from a spiritual component. Georg Ernst Stahl's 18th-century animism was adopted by Edward Burnett Tylor, the founder of cultural anthropology, who presented his initial ideas about the history of religion in his 1865 Researches into the Early History of Mankind [20] : vi and developed them in volumes one (1871) and two (1874) of Primitive Culture. [20] : 1

Tylor's cultural evolution

In Tylor's cultural anthropology, other primates did not appear to possess culture. [note 1]

Tylor did not try to find evidence of a non-cultural human state because he considered it unreachable, "a condition not far removed from that of the lower animals" and "savage life as in some sort representing an early known state." [20] : 33 He described such a hypothetical state as "the human savage naked in both mind and body, and destitute of laws, or arts, or ideas, and almost of language". [20] : 30 According to Tylor, speculation about an acultural state is impossible. Using the method of comparative culture, similar to comparative anatomy and the comparative method of historical linguistics and following John Lubbock, he drew up a dual classification of cultural traits (memes and memeplexes). His categories were "savage" and "civilised". Tylor wrote, "From an ideal point of view, civilization may be looked upon as the general improvement of mankind by higher organization of the individual and of society ... " [20] : 24 and identified his model with the "progression-theory of civilization". [20] : 81

Evolution of religion

Tylor cited a "minimum definition" of religion as "the belief in Spiritual Beings". [20] : 383 Noting that no savage societies lack religion and that the initial state of a religious man is beyond reach, he enumerated two stages in the evolution of religion: a simple belief in individual animae (or Doctrine of Souls) and the elaboration of dogma. The dogmas are systems of higher spirits commanding phases of nature. In volume two of Primitive Culture, Tylor called this stage the Doctrine of Spirits. [20] : 108–110 He used the word "animism" in two different senses. [20] : 385 The first is religion itself: a belief in the spiritual as an effective energy, shared by every specific religion. In his progression theory, an undogmatic version preceded rational theological systems. Animism is the simple Theory of the Soul, which comparative religion attempts to reconstruct.

Tylor's work predated Codrington's, and he was unfamiliar with the latter. The concept of mana occasioned a revision of Tylor's view of the evolution of religion. The first anthropologist to formulate a revision (which he called "pre-animistic religion") was Robert Ranulph Marett, in a series of papers collected and published as Threshold of Religion. In its preface he takes credit for the adjective "pre-animistic" but not the noun "pre-animism", although he does not attribute it. [21] : xxi

According to Marett, "Animism will not suffice as a minimum definition of religion." Tylor had used the term "natural religion", [20] : 386 consistent with Georg Ernst Stahl's concept of a natural spiritual energy. The soul of an animal, for example, is its vital principle. Marett wrote that "one must dig deeper" to find the "roots of religion".[ citation needed ]

Pre-animism

Describing pre-animism, Marett cited the Melanesian mana (primarily with Codrington's work): "When the science of Comparative Religion employs a native expression such as mana, it is obliged to disregard to some extent its original or local meaning. Science, then, may adopt mana as a general category ... ". [21] : 99 In Melanesia the animae are the souls of living men, the ghosts of deceased men, and spirits "of ghost-like appearance" or imitating living people. Spirits can inhabit other objects, such as animals or stones. [21] : 115–120

The most significant property of mana is that it is distinct from, and exists independently of, its source. Animae act only through mana. It is impersonal, undistinguished, and (like energy) transmissible between objects, which can have more or less of it. Mana is perceptible, appearing as a "Power of awfulness" (in the sense of awe or wonder). [21] : 12–13 Objects possessing it impress an observer with "respect, veneration, propitiation, service" emanating from the mana's power. Marett lists a number of objects habitually possessing mana: "startling manifestations of nature", "curious stones", animals, "human remains", blood, [21] : 2 thunderstorms, eclipses, eruptions, glaciers, and the sound of a bullroarer. [21] : 14–17

If mana is a distinct power, it may be treated distinctly. Marett distinguishes spells, which treat mana quasi-objectively, and prayers (which address the anima). An anima may have departed, leaving mana in the form of a spell which can be addressed by magic. Although Marett postulates an earlier pre-animistic phase, a "rudimentary religion" or "magico-religious" phase in which the mana figures without animae, "no island of pure 'pre-animism' is to be found." [21] : xxvi Like Tylor, he theorizes a thread of commonality between animism and pre-animism identified with the supernatural—the "mysterious", as opposed to the reasonable. [21] : 22

Durkheim's totemism

In 1912, French sociologist Émile Durkheim examined totemism, the religion of the Aboriginal Australians, from a sociological and theological point of view, describing collective effervescence as originating in the idea of the totemic principle or Mana.

Criticism

In 1936, Ian Hogbin criticised the universality of Marett's pre-animism: "Mana is by no means universal and, consequently, to adopt it as a basis on which to build up a general theory of primitive religion is not only erroneous but indeed fallacious". [22] However, Marett intended the concept as an abstraction. [21] : 99 Spells, for example, may be found "from Central Australia to Scotland." [21] : 55

Early 20th-century scholars also saw mana as a universal concept, found in all human cultures and expressing fundamental human awareness of a sacred life energy. In his 1904 essay, "Outline of a General Theory of Magic", Marcel Mauss drew on the writings of Codrington and others to paint a picture of mana as "power par excellence , the genuine effectiveness of things which corroborates their practical actions without annihilating them". [23] : 111 Mauss pointed out the similarity of mana to the Iroquois orenda and the Algonquian manitou, convinced of the "universality of the institution"; [23] : 116 "a concept, encompassing the idea of magical power, was once found everywhere". [23] : 117

Mauss and his collaborator, Henri Hubert, were criticised for this position when their 1904 Outline of a General Theory of Magic was published. "No one questioned the existence of the notion of mana", wrote Mauss's biographer Marcel Fournier, "but Hubert and Mauss were criticized for giving it a universal dimension". [24] Criticism of mana as an archetype of life energy increased. According to Mircea Eliade, the idea of mana is not universal; in places where it is believed, not everyone has it, and "even among the varying formulae (mana, wakan, orenda, etc.) there are, if not glaring differences, certainly nuances not sufficiently observed in the early studies". [25] "With regard to these theories founded upon the primordial and universal character of mana, we must say without delay that they have been invalidated by later research". [26]

Hoolbrad [27] argued in a paper included in the seminal volume “Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically”, that the concept of mana highlights a significant theoretical assumption in Anthropology : that matter, and meaning are separate. A hotly debated issue, Hoolbrad suggests that mana provides motive to re-evaluate the division assumed between matter and meaning in social research. His work is part of the ontological turn in Anthropology, a paradigm shift that aims to take seriously the ontology of other cultures [28]