Related Research Articles

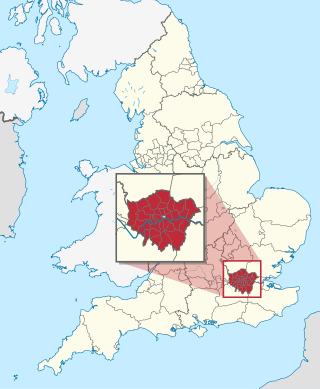

The London boroughs are the 32 local authority districts that together with the City of London make up the administrative area of Greater London, England; each is governed by a London borough council. The present London boroughs were all created at the same time as Greater London on 1 April 1965 by the London Government Act 1963 and are a type of local government district. Twelve were designated as Inner London boroughs and twenty as Outer London boroughs. The City of London, the historic centre, is a separate ceremonial county and sui generis local government district that functions quite differently from a London borough. However, the two counties together comprise the administrative area of Greater London as well as the London Region, all of which is also governed by the Greater London Authority.

The Greater London Council (GLC) was the top-tier local government administrative body for Greater London from 1965 to 1986. It replaced the earlier London County Council (LCC) which had covered a much smaller area. The GLC was dissolved in 1986 by the Local Government Act 1985 and its powers were devolved to the London boroughs and other entities. A new administrative body, known as the Greater London Authority (GLA), was established in 2000.

Metropolitan counties are a type of county-level administrative division of England. There are six metropolitan counties, which each cover large urban areas, with populations between 1 and 3 million. They were created in 1974 and are each divided into several metropolitan districts or boroughs. Following the abolition of metropolitan county councils in 1986, metropolitan counties no longer form a part of local government in England. Most of their functions were devolved to the metropolitan boroughs, making the boroughs effectively unitary authorities; any remaining functions were taken over by joint boards.

Avon was a non-metropolitan and ceremonial county in the west of England that existed between 1974 and 1996. The county was named after the River Avon, which flows through the area. It was formed from the county boroughs of Bristol and Bath, together with parts of the administrative counties of Gloucestershire and Somerset.

The counties of England are areas used for different purposes, which include administrative, geographical, cultural and political demarcation. The term "county" is defined in several ways and can apply to similar or the same areas used by each of these demarcation structures. These different types of county each have a more formal name but are commonly referred to as just "counties". The current arrangement is the result of incremental reform.

County borough is a term introduced in 1889 in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to refer to a borough or a city independent of county council control, similar to the unitary authorities created since the 1990s. An equivalent term used in Scotland was a county of city. They were abolished by the Local Government Act 1972 in England and Wales, but continue in use for lieutenancy and shrievalty in Northern Ireland. In the Republic of Ireland they remain in existence but have been renamed cities under the provisions of the Local Government Act 2001. The Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 re-introduced the term for certain "principal areas" in Wales. Scotland did not have county boroughs but instead had counties of cities. These were abolished on 16 May 1975. All four Scottish cities of the time—Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, and Glasgow—were included in this category. There was an additional category of large burgh in the Scottish system, which were responsible for all services apart from police, education and fire.

The Redcliffe-Maud Report was published in 1969 by the Royal Commission on Local Government in England, under the chairmanship of Lord Redcliffe-Maud. Although the commission's proposals were broadly accepted by the Labour government, they were set aside by the Conservative government elected in 1970.

The Local Government Act 1972 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant Acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Government of 1970–74.

The Metropolitan Police District (MPD) is the police area which is policed by the Metropolitan Police Service in London. It currently consists of the Greater London region, excluding the City of London. The Metropolitan Police District was created by the Metropolitan Police Act 1829 as an ad hoc area of administration because the built-up area of London spread at the time into many parishes and counties without an established boundary. The district expanded as the built up area grew and stretched some distance into rural land. When county police forces were set up in England, those of Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent and Surrey did not cover the parts of the counties within the MPD, while Middlesex did not have a county force. Similarly, boroughs in the MPD that elsewhere would have been entitled to their own police force did not have them.

The Metropolitan Water Board was a municipal body formed in 1903 to manage the water supply in London, UK. The members of the board were nominated by the local authorities within its area of supply. In 1904 it took over the water supply functions from the eight private water companies which had previously supplied water to residents of London. The board oversaw a significant expansion of London's water supply infrastructure, building several new reservoirs and water treatment works.

The London Government Act 1963 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created Greater London and a new local government structure within it. The Act significantly reduced the number of local government districts in the area, resulting in local authorities responsible for larger areas and populations. The upper tier of local government was reformed to cover the whole of the Greater London area and with a more strategic role; and the split of functions between upper and lower tiers was recast. The Act classified the boroughs into inner and outer London groups. The City of London and its corporation were essentially unreformed by the legislation. Subsequent amendments to the Act have significantly amended the upper tier arrangements, with the Greater London Council abolished in 1986, and the Greater London Authority introduced in 2000. As of 2016, the London boroughs are more or less identical to those created in 1965, although with some enhanced powers over services such as waste management and education.

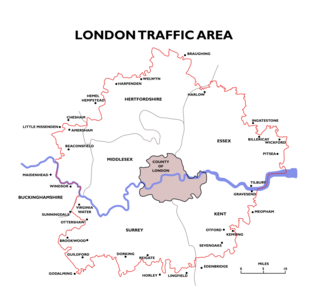

The London Traffic Area was established by the London Traffic Act 1924 to regulate the increasing amount of motor traffic in the London area. The LTA was abolished in 1965 on the establishment of the Greater London Council.

The Local Government Act 1958 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom affecting local government in England and Wales outside London. Among its provisions it included the establishment of Local Government Commissions to review the areas and functions of local authorities, and introduced new procedures for carrying these into action.

The history of local government in England is one of gradual change and evolution since the Middle Ages. England has never possessed a formal written constitution, with the result that modern administration is based on precedent, and is derived from administrative powers granted to older systems, such as that of the shires.

Havering London Borough Council is the local authority for the London Borough of Havering in Greater London, England. It is a London borough council, one of 32 in the United Kingdom capital of London. Havering is divided into 18 wards, each electing three councillors. Since May 2018, Havering London Borough Council has been in no overall control. It comprises 22 Havering Residents Association members, 20 Conservative Party members, 9 Labour Party members, 3 East Havering Residents' Group members and 1 Upminster and Cranham Residents Association member. The council was created by the London Government Act 1963 and replaced two local authorities: Hornchurch Urban District Council and Romford Borough Council.

Hackney London Borough Council is the local government authority for the London Borough of Hackney, London, England, one of 32 London borough councils. The council is unusual in the United Kingdom local government system in that its executive function is controlled by a directly elected mayor of Hackney, currently Philip Glanville of the Labour Party. Hackney comprises 19 wards, each electing three councillors. Following the May 2018 election, Hackney London Borough Council consists of 52 Labour Party councillors and 5 Conservative Party councillors. The council was created by the London Government Act 1963 whereby it replaced three local authorities: Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council, Shoreditch Metropolitan Borough Council and Stoke Newington Metropolitan Borough Council.

The Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London, also known as the Herbert Commission, was established in 1957 and published its report in 1960. The report made recommendations for the overhaul of the administration of the capital. They were modified and implemented by the London Government Act 1963.

The regions, formerly known as the government office regions, are the highest tier of sub-national division in England. They were established in 1994 and follow the 1974–96 county borders. They are a continuation of the former 1940s standard regions which followed the 1889–1974 administrative county borders. Between 1994 and 2011, nine regions had partly devolved functions; they no longer fulfil this role, continuing to be used for limited statistical purposes.

The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) was the statutory body established under the Local Government Act 1972 to settle the boundaries, names and electoral arrangements of the non-metropolitan districts which came into existence in 1974, and for their periodic review. The stated purpose of the LGBCE was to ensure "that the whole system does not get frozen into the form which has been adopted as appropriate in the 1970s". In the event it made no major changes and was replaced in 1992 by the Local Government Commission for England.

The Royal Commission on London Traffic was a Royal commission established in 1903 with a remit to review and report on how transport systems should be developed for London and the surrounding area. It produced a report in eight volumes published in 1905 and made recommendations on the character, administration and routing of traffic in London.

References

- ↑ Young, Ken; Garside, Patricia L (1982). Metropolitan London: Politics and Urban Change 1837-1981 . London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6331-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Greater London. Report of Royal Commission". The Times . 22 March 1923. p. 9.

- 1 2 Robson, William A (1939). The Government and Misgovernment of London. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 294.

- 1 2 Saint, Andrew (1989). Politics and the people of London: the London County Council, 1889-1965. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 105–107. ISBN 978-1-85285-029-6 . Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Elaine Harrison (1995). "List of commissions and officials: 1920-1929 (nos. 175-201)". British History Online. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "No. 32497". The London Gazette . 25 October 1921. p. 8364.

- ↑ "London Government Anomalies. Inquiry To Open To-Day". The Times . 6 December 1921. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Greater London. Royal Commission Opens, Evidence On Existing Powers". The Times . 7 December 1921. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 "Greater London. Case For Central Authority, Area And Powers". The Times . 14 December 1921. p. 5.

- ↑ Smellie, K B (1946). A History of Local Government. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 183.

- ↑ "Greater London Inquiry. L.C.C. And Hospitals, The Equalization Of Rates". The Times . 1 February 1922. p. 6.

- ↑ "London Government. "Mud-Throwing" At Local Authorities". The Times . 27 April 1922. p. 11.

- ↑ "Transport Competition In London. Sir H. Maybury's Views". The Times . 7 December 1922. p. 15.

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission on London Government (Cmd. 1830)

- ↑ "Political Notes. The Position In Ireland, London Traffic". The Times . 10 July 1923. p. 14.

- ↑ "London Traffic. Draft Bill Ready For Parliament. Growing Congestion". The Times . 17 January 1924. p. 9.

- ↑ "Political Notes. Government And Housing, London Traffic Bill". The Times . 18 March 1924. p. 14.

- ↑ "Parliament, London Traffic Bill". The Times . 26 March 1924. p. 7.

- ↑ "London Traffic Act. Delay In Appointment Of Advisory Committee". The Times . 27 August 1924. p. 7.

- ↑ "Traffic Congestion. New Act In Force To-Day". The Times . 1 October 1924. p. 12.