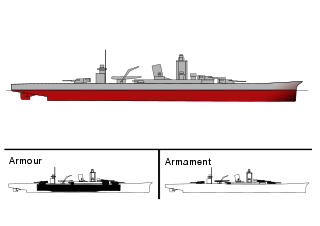

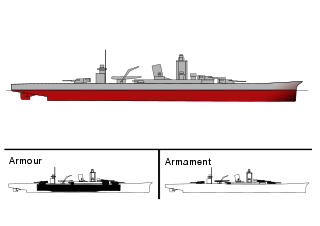

The battlecruiser was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attributes. Battlecruisers typically had thinner armour and a somewhat lighter main gun battery than contemporary battleships, installed on a longer hull with much higher engine power in order to attain greater speeds. The first battlecruisers were designed in the United Kingdom, as a development of the armoured cruiser, at the same time as the dreadnought succeeded the pre-dreadnought battleship. The goal of the design was to outrun any ship with similar armament, and chase down any ship with lesser armament; they were intended to hunt down slower, older armoured cruisers and destroy them with heavy gunfire while avoiding combat with the more powerful but slower battleships. However, as more and more battlecruisers were built, they were increasingly used alongside the better-protected battleships.

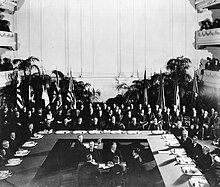

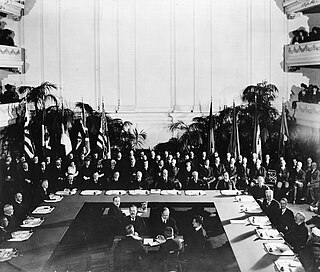

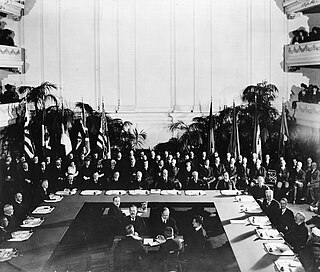

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Naval Conference in Washington, D.C. from November 1921 to February 1922 and signed by the governments of the British Empire, United States, France, Italy, and Japan. It limited the construction of battleships, battlecruisers and aircraft carriers by the signatories. The numbers of other categories of warships, including cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, were not limited by the treaty, but those ships were limited to 10,000 tons displacement each.

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 and the London Naval Treaty of 1930. Heavy cruisers were generally larger, more heavily-armed and more heavily-armoured than light cruisers while being smaller, faster, and more lightly-armed and armoured than battlecruisers and battleships. Heavy cruisers were assigned a variety of roles ranging from commerce raiding to serving as 'cruiser-killers,' i.e. hunting and destroying similarly-sized ships.

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast enough to outrun any battleship it encountered.

The Second London Naval Treaty was an international treaty signed as a result of the Second London Naval Disarmament Conference held in London. The conference started on 9 December 1935 and the treaty was signed by the participating nations on 25 March 1936.

The North Carolina class were a pair of fast battleships, North Carolina and Washington, built for the United States Navy in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

The Alaska-class were six large cruisers ordered before World War II for the United States Navy (USN), of which only two were completed and saw service late in the war. The USN designation for the ships of this class was 'large cruiser' (CB), a designation unique to the Alaska-class, and the majority of leading reference works consider them as such. However, various other works have alternately described these ships as battlecruisers despite the USN having never classified them as such, and having actively discouraged the use of the term in describing the class. The Alaskas were all named after territories or insular areas of the United States, signifying their intermediate status between larger battleships and smaller heavy and light cruisers.

The Delaware-class battleships of the United States Navy were the second class of American dreadnoughts; the class comprised two ships: Delaware and North Dakota. With this class, the 16,000 long tons (16,257 t) limit imposed on capital ships by the United States Congress was waived, which allowed designers at the Navy's Bureau of Construction and Repair to correct what they considered flaws in the preceding South Carolina class and produce ships not only more powerful but also more effective and rounded overall. Launched in 1909, these ships became the first in US naval history to exceed 20,000 long tons (20,321 t).

The Lion class was a class of six fast battleships designed for the Royal Navy (RN) in the late 1930s. They were a larger, improved version of the preceding King George V class, with 16-inch (406 mm) guns. Only two ships were laid down before the Second World War began in September 1939 and a third was ordered during the war, but their construction was suspended shortly afterwards. The design was modified in light of war experience in 1942, but the two ships already begun were scrapped later in the year.

The Geneva Naval Conference was a conference held to discuss naval arms limitation, held in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1927. The aim of the conference was to extend the existing limits on naval construction which had been agreed in the Washington Naval Treaty. The Washington Treaty had limited the construction of battleships and aircraft carriers, but had not limited the construction of cruisers, destroyers or submarines.

A fast battleship was a battleship which in concept emphasised speed without undue compromise of either armor or armament. Most of the early World War I-era dreadnought battleships were typically built with low design speeds, so the term "fast battleship" is applied to a design which is considerably faster. The extra speed of a fast battleship was normally required to allow the vessel to carry out additional roles besides taking part in the line of battle, such as escorting aircraft carriers.

Design B-65 was a class of cruisers planned by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) before and during World War II. The IJN referred to this design as a 'Super Type A' cruiser; It was larger than most heavy cruisers but smaller than most battlecruisers, and as such, has been variously described as a 'super-heavy cruiser,' a 'super cruiser,' or as a 'cruiser-killer.' As envisioned by the IJN, the cruisers were to play a key role in the Night Battle Force portion of the "Decisive battle" strategy which Japan hoped, in the event of war, to employ against the United States Navy.

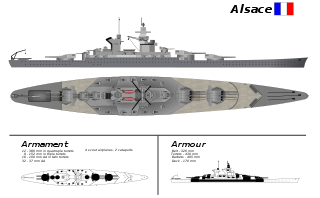

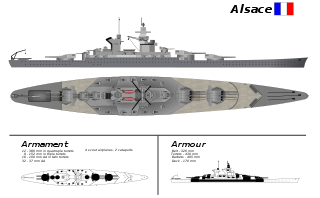

The Alsace class was a pair of fast battleships planned by the French Navy in the late 1930s in response to German plans to build two H-class battleships after the Second London Naval Treaty collapsed. The Alsace design was based on variants of the Richelieu class, and three proposals were submitted by the design staff. The proposed armament included nine or twelve 380 mm (15 in) guns or nine 406 mm (16 in) guns, but no choice was definitively made before the program ended in mid-1940. According to one pair of historians, logistical considerations—including the size of the 12-gun variant and the introduction of a new shell caliber for the 406 mm version—led the naval command to settle on the nine 380 mm design. But another pair of authors disagree, believing that the difficulty of designing and manufacturing a three-gun turret would have caused prohibitive delays during wartime, making the third, largest variant the most likely to have been built. The ships would have forced the French government to make significant improvements to its harbor and shipyard facilities, as the smaller Richelieus already stretched the limitations of existing shipyards. With construction of the first member of the class scheduled for 1941, the plan was terminated by the German victory in the Battle of France in May–June 1940.

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's HMS Dreadnought, had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts. Her design had two revolutionary features: an "all-big-gun" armament scheme, with an unprecedented number of heavy-calibre guns, and steam turbine propulsion. As dreadnoughts became a crucial symbol of national power, the arrival of these new warships renewed the naval arms race between the United Kingdom and Germany. Dreadnought races sprang up around the world, including in South America, lasting up to the beginning of World War I. Successive designs increased rapidly in size and made use of improvements in armament, armour, and propulsion throughout the dreadnought era. Within five years, new battleships outclassed Dreadnought herself. These more powerful vessels were known as "super-dreadnoughts". Most of the original dreadnoughts were scrapped after the end of World War I under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, but many of the newer super-dreadnoughts continued serving throughout World War II.

The Number 13-class battleship was a planned class of four fast battleships to be built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the 1920s. The ships never received any names, being known only as Numbers 13–16. They were intended to reinforce Japan's "eight-eight fleet" of eight battleships and eight battlecruisers after the United States announced a major naval construction program in 1919. The Number 13 class was designed to be superior to all other existing battleships, planned or building. After the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty in 1922, they were cancelled in November 1923 before construction could begin.

The Eight-Eight Fleet Program was a Japanese naval strategy formulated for the development of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the first quarter of the 20th century, which stipulated that the navy should include eight first-class battleships and eight armoured cruisers or battlecruisers.

The Amagi class was a series of four battlecruisers planned for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) as part of the Eight-eight fleet in the early 1920s. The ships were to be named Amagi, Akagi, Atago, and Takao. The Amagi design was essentially a lengthened version of the Tosa-class battleship, but with a thinner armored belt and deck, a more powerful propulsion system, and a modified secondary armament arrangement. They were to have carried the same main battery of ten 41 cm (16.1 in) guns and been capable of a top speed of 30 knots.

The Lexington-class battlecruisers were officially the only class of battlecruiser to ever be ordered by the United States Navy. While these six vessels were requested in 1911 as a reaction to the building by Japan of the Kongō class, the potential use for them in the U.S. Navy came from a series of studies by the Naval War College which stretched over several years and predated the existence of the first battlecruiser, HMS Invincible. The fact they were not approved by Congress at the time of their initial request was due to political, not military considerations.