Jainism, also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras, with the first in the current time cycle being Rishabhadeva, whom the tradition holds to have lived millions of years ago, the twenty-third tirthankara Parshvanatha, whom historians date to the 9th century BCE, and the twenty-fourth tirthankara Mahavira, around 600 BCE. Jainism is considered an eternal dharma with the tirthankaras guiding every time cycle of the cosmology. Central to understanding Jain philosophy is the concept of bhedvigyān, or the clear distinction in the nature of the soul and non-soul entities. This principle underscores the innate purity and potential for liberation within every soul, distinct from the physical and mental elements that bind it to the cycle of birth and rebirth. Recognizing and internalizing this separation is essential for spiritual progress and the attainment of samyak darshan or self realization, which marks the beginning of the aspirant's journey towards liberation. The three main pillars of Jainism are ahiṃsā (non-violence), anekāntavāda (non-absolutism), and aparigraha (asceticism).

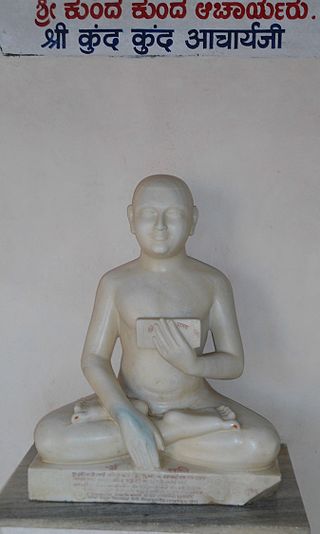

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the second century CE or later.

Anekāntavāda is the Jain doctrine about metaphysical truths that emerged in ancient India. It states that the ultimate truth and reality is complex and has multiple aspects and viewpoints.

Tattvārthasūtra, meaning "On the Nature [artha] of Reality [tattva]" is an ancient Jain text written by Acharya Umaswami in Sanskrit, sometime between the 2nd- and 5th-century CE.

In Jainism, kashaya are aspects of a person that can be gained during their worldly life. According to the Jaina religion, as long as a person has Kashayas, they will not escape the cycle of life and death. There are four different kinds of Kashayas, each being able to gain their own kinds of intensity.

Karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology in Jainism. Human moral actions form the basis of the transmigration of the soul. The soul is constrained to a cycle of rebirth, trapped within the temporal world, until it finally achieves liberation. Liberation is achieved by following a path of purification.

Samayasāra is a famous Jain text composed by Acharya Kundakunda in 439 verses. Its ten chapters discuss the nature of Jīva, its attachment to Karma and Moksha (liberation). Samayasāra expounds the Jain concepts like Karma, Asrava, Bandha (Bondage), Samvara (stoppage), Nirjara (shedding) and Moksha.

Nirjara is one of the seven fundamental principles, or Tattva in Jain philosophy, and refers to the shedding or removal of accumulated karmas from the atma (soul), essential for breaking free from samsara, the cycle of birth-death and rebirth, by achieving moksha, liberation.

Jain philosophy or Jaina philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system of the Jain religion. It comprises all the philosophical investigations and systems of inquiry that developed among the early branches of Jainism in ancient India following the parinirvāṇa of Mahāvīra. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence: the living, conscious, or sentient beings (jīva) and the non-living or material entities (ajīva).

Kevala jnana or Kevala gyana, also known as Kaivalya, means omniscience in Jainism and is roughly translated as complete understanding or supreme wisdom.

Sanskrit moksha or Prakrit mokkha refers to the liberation or salvation of a soul from saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. It is a blissful state of existence of a soul, attained after the destruction of all karmic bonds. A liberated soul is said to have attained its true and pristine nature of Unlimited bliss, Unlimited knowledge and Unlimited perception. Such a soul is called siddha and is revered in Jainism.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Jain philosophy explains that nine or seven tattva constitute reality. These are:

- jīva – the soul which is characterized by consciousness

- ajīva – the non-soul

- puṇya (alms-deed) – which purifies the soul and provide happiness to others

- pāpa – which impurifies the soul

- āsrava (influx) – inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul.

- bandha (bondage) – mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas.

- saṃvara (stoppage) – obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul.

- nirjarā – separation or falling-off of parts of karmic matter from the soul.

- mokṣa (liberation) – complete annihilation of all karmic matter.

Kanji Swami (1890–1980) was a teacher of Jainism. He was deeply influenced by the Samayasāra of Kundakunda in 1932. He lectured on these teachings for 45 years to comprehensively elaborate on the philosophy described by Kundakunda and others. He was given the title of "Koh-i-Noor of Kathiawar" by the people who were influenced by his religious teachings and philosophy.

Asrava is one of the tattva or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It refers to the influence of body and mind causing the soul to generate karma.

Jīva or Ātman is a philosophical term used within Jainism to identify the soul. As per Jain cosmology, jīva or soul is the principle of sentience and is one of the tattvas or one of the fundamental substances forming part of the universe. The Jain metaphysics, states Jagmanderlal Jaini, divides the universe into two independent, everlasting, co-existing and uncreated categories called the jiva (soul) and the ajiva. This basic premise of Jainism makes it a dualistic philosophy. The jiva, according to Jainism, is an essential part of how the process of karma, rebirth and the process of liberation from rebirth works.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Akalanka was a Jain logician whose Sanskrit-language works are seen as landmarks in Indian logic. He lived from 720 to 780 A.D. and belonged to the Digambara sect of Jainism. His work Astasati, a commentary on Aptamimamsa of Acharya Samantabhadra deals mainly with jaina logic. He was a contemporary of Rashtrakuta king Krishna I. He is the author of Tattvārtharājavārtika, a commentary on major Jain text Tattvartha Sutra. He greatly contributed to the development of the philosophy of Anekantavada and is therefore called the "Master of Jain logic".

Yogaśāstra is a 12th-century Sanskrit text by Hemachandra on Śvetāmbara Jainism. It is a treatise on the "rules of conduct for laymen and ascetics", wherein "yoga" means "ratna-traya", i.e. right belief, right knowledge and right conduct for a Sadhaka. As a manual with an extensive auto-commentary called Svopajnavrtti, it was instrumental to the survival and growth of Śvetāmbara tradition in western Indian states such as Gujarat and the spread of Sanskrit culture in Jainism.

In Jain tradition, twelve contemplations, are the twelve mental reflections that a Jain ascetic and a practitioner should repeatedly engage in. These twelve contemplations are also known as Barah anuprekṣā or Barah bhāvana. According to Jain Philosophy, these twelve contemplations pertain to eternal truths like nature of universe, human existence, and karma on which one must meditate. Twelve contemplations is an important topic that has been developed at all epochs of Jain literature. They are regarded as summarising fundamental teachings of the doctrine. Stoppage of new Karma is called Samvara. Constant engagement on these twelve contemplations help the soul in samvara or stoppage of karmas.