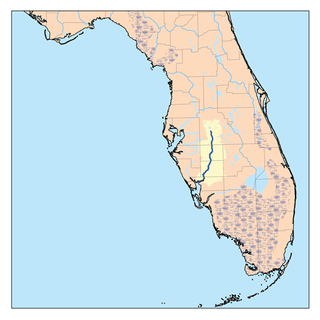

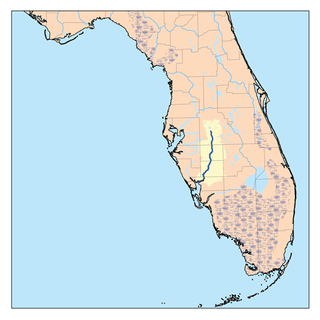

The Everglades is a natural region of flooded grasslands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orlando with the Kissimmee River, which discharges into the vast but shallow Lake Okeechobee. Water leaving the lake in the wet season forms a slow-moving river 60 miles (97 km) wide and over 100 miles (160 km) long, flowing southward across a limestone shelf to Florida Bay at the southern end of the state. The Everglades experiences a wide range of weather patterns, from frequent flooding in the wet season to drought in the dry season. Throughout the 20th century, the Everglades suffered significant loss of habitat and environmental degradation.

Ponce de Leon is a town in Holmes County, Florida, United States. The Town of Ponce de Leon was named after Spanish explorer, Juan Ponce de León. It is part of the Florida Panhandle in North Florida. The population was 504 at the 2020 census, down from 598 at the 2010 census.

Everglades National Park is an American national park that protects the southern twenty percent of the original Everglades in Florida. The park is the largest tropical wilderness in the United States and the largest wilderness of any kind east of the Mississippi River. An average of one million people visit the park each year. Everglades is the third-largest national park in the contiguous United States after Death Valley and Yellowstone. UNESCO declared the Everglades & Dry Tortugas Biosphere Reserve in 1976 and listed the park as a World Heritage Site in 1979, and the Ramsar Convention included the park on its list of Wetlands of International Importance in 1987. Everglades is one of only three locations in the world to appear on all three lists.

A spring is a natural exit point at which groundwater emerges out of the aquifer and flows onto the top of the Earth's crust (pedosphere) to become surface water. It is a component of the hydrosphere, as well as a part of the water cycle. Springs have long been important for humans as a source of fresh water, especially in arid regions which have relatively little annual rainfall.

The St. Johns River is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and it is the most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At 310 miles (500 km) long, it flows north and winds through or borders twelve counties. The drop in elevation from headwaters to mouth is less than 30 feet (9 m); like most Florida waterways, the St. Johns has a very slow flow speed of 0.3 mph (0.13 m/s), and is often described as "lazy".

The Choctawhatchee River is a 141-mile-long (227 km) river in the southern United States, flowing through southeast Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida before emptying into Choctawhatchee Bay in Okaloosa and Walton counties. The river, the bay and their adjacent watersheds collectively drain 5,350 square miles (13,900 km2).

The Floridan aquifer system, composed of the Upper and Lower Floridan aquifers, is a sequence of Paleogene carbonate rock which spans an area of about 100,000 square miles (260,000 km2) in the southeastern United States. It underlies the entire state of Florida and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

The San Marcos River rises from the San Marcos Springs, the location of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, in San Marcos, Texas. The springs are home to several threatened or endangered species, including the Texas blind salamander, fountain darter, and Texas wild rice. The river is a popular recreational area, and is frequented for tubing, canoeing, swimming, and fishing.

The Edwards Aquifer is one of the most prolific artesian aquifers in the world. Located on the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau in the U.S. state of Texas, it is the source of drinking water for two million people, and is the primary water supply for agriculture and industry in the aquifer's region. Additionally, the Edwards Aquifer feeds the Comal and San Marcos Springs, provides springflow for recreational and downstream uses in the Nueces, San Antonio, Guadalupe, and San Marcos river basins, and is home to several unique and endangered species.

Lake Jackson is a shallow, prairie lake on the north side of Leon County, Florida, United States, near Tallahassee, with two major depressions or sinkholes known as Porter Sink and Lime Sink.

Lake Miccosukee is a large swampy prairie lake in northern Jefferson County, Florida, located east of the settlement of Miccosukee. A small portion of the lake, its northwest corner, is located in Leon County. The small town of Miccosukee, Florida is located on the north eastern shore of the lake in Leon County.

The Florida Trail is one of eleven National Scenic Trails in the United States. It currently runs 1,500 miles (2,400 km), from Big Cypress National Preserve to Fort Pickens at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Pensacola Beach. Also known as the Florida National Scenic Trail, the Florida Trail provides permanent non-motorized recreation opportunity for hiking and other compatible activities and is within an hour of most Floridians. The Florida National Scenic Trail is designated as a National Scenic Trail by the National Trails System Act of 1968.

Garald G. Parker Sr. (1905–2000) was a hydrologist and is known as the "Father of Florida groundwater hydrology." Parker also named the principal artesian aquifer the Floridan Aquifer.

Surficial aquifers are shallow aquifers typically less than 50 feet (15 m) thick, but larger surficial aquifers of about 60 feet (18 m) have been mapped. They mostly consist of unconsolidated sand enclosed by layers of limestone, sandstone or clay and the water is commonly extracted for urban use. The aquifers are replenished by streams and from precipitation and can vary in volume considerably as the water table fluctuates. Being shallow, they are susceptible to contamination by fuel spills, industrial discharge, landfills, and saltwater. Parts of southeastern United States are dependent on surficial aquifers for their water supplies.

The Chisca were a tribe of Native Americans living in present-day eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia in the 16th century, and in present-day Alabama, Georgia, and Florida in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, by which time they were known as Yuchi. The Hernando de Soto expedition heard of, and may have had brief contact with, the Chisca in 1540. The Juan Pardo expeditions of 1566 and 1568 encountered the Chisca, and engaged in battles with them. By early in the 17th century, Chisca people were present in several parts of Spanish Florida, engaged at various times and places in alternately friendly or hostile relations with the Spanish and the peoples of the Spanish mission system. After the capture of a fortified Chisca town by the Spanish and Apalachee in 1677, some Chisca took refuge in northern Tennessee, where they were absorbed into the Shawnee, and in Muscogee towns in Alabama. Around the turn of the 18th century some Chisca, by then generally called Yuchi, joined the Apalachicola Province towns that resettled around Ochisi Creek in central Georgia, thus becoming part of the "Lower Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy". A few Chiscas remained in western Florida into the middle of the 18th century.

Colt Creek State Park is a Florida State Park in Central Florida, 16 miles (26 km) north of Lakeland off of State Road 471. This 5,067 acre park nestled within the Green Swamp Wilderness Area and named after one of the tributaries that flows through the property was opened to the public on January 20, 2007. Composed mainly of pine flatwoods, cypress domes and open pasture land, this piece of pristine wilderness is home to many animal species including the American bald eagle, Southern fox squirrel, gopher tortoise, white-tailed deer, wild turkey and bobcat.

The Ocala Limestone is a late Eocene geologic formation of exposed limestones near Ocala, Marion County, Florida.

Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park is a Florida State Park in Wakulla County, Florida, United States. This 6,000 acre (24 km2) wildlife sanctuary, located south of Tallahassee, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and designated a National Natural Landmark.

Kissingen Spring was a natural spring formerly flowing in Polk County, Southwest Florida. It was also a venue for recreation until it dried up in 1950. Hundreds of wells drilled into the Floridan Aquifer may have caused the demise of the springs. Its site is located near the northern end of Peace River, approximately 3/4 mile east of U.S. Highway 17 and 4 miles south of Florida SR 60 / south of Bartow.

Lake Barco is a lake in Putnam County, Florida, United States. It is within the Ordway-Swisher Biological Station of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. It is roughly circular, about 200 metres (660 ft) in diameter. The nearest settlement is Melrose, Florida, about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) to the northwest.