The Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front, from July to November 1917, for control of the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres in West Flanders, as part of a strategy decided by the Allies at conferences in November 1916 and May 1917. Passchendaele lies on the last ridge east of Ypres, 5 mi (8 km) from Roulers, a junction of the Bruges-(Brugge)-to-Kortrijk railway. The station at Roulers was on the main supply route of the German 4th Army. Once Passchendaele Ridge had been captured, the Allied advance was to continue to a line from Thourout to Couckelaere (Koekelare).

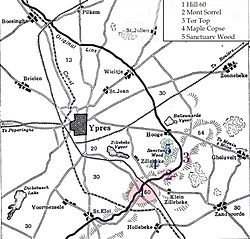

The Capture of Hill 60 took place near Hill 60 south of Ypres on the Western Front, during the First World War. Hill 60 had been captured by the German 30th Division on 11 November 1914, during the First Battle of Ypres. Initial French preparations to raid the hill were continued by the British 28th Division, which took over the line in February 1915 and then by the 5th Division. The plan was expanded into an ambitious attempt to capture the hill, despite advice that Hill 60 could not be held unless the nearby Caterpillar ridge was also occupied. It was found that Hill 60 was the only place in the area not waterlogged and a French 3 ft × 2 ft mine gallery was extended.

Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt was a German field fortification, west of the village of Beaumont Hamel on the Somme. The redoubt was built after the end of the Battle of Albert and as French and later British attacks on the Western Front became more formidable, the Germans added fortifications and trench positions near the original lines around Hawthorn Ridge. At 7:20 a.m. on 1 July 1916, the British fired a huge mine beneath the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. Sprung ten minutes before zero hour, the mine was one of 19 mines detonated on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Geoffrey Malins, one of two official war cameramen, filmed the detonation of the mine. The attack on the redoubt by part of the 29th Division of VIII Corps was a costly failure.

The Ypres Salient, around Ypres, in Belgium, was the scene of several battles and a major part of the Western Front during World War I.

The Battle of Messines was an attack by the British Second Army, on the Western Front, near the village of Messines in West Flanders, Belgium, during the First World War. The Nivelle Offensive in April and May had failed to achieve its more grandiose aims, had led to the demoralisation of French troops and confounded the Anglo-French strategy for 1917. The attack forced the Germans to move reserves to Flanders from the Arras and Aisne fronts, relieving pressure on the French.

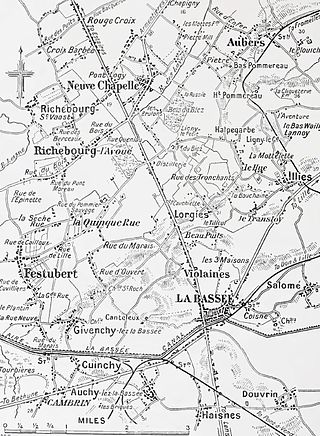

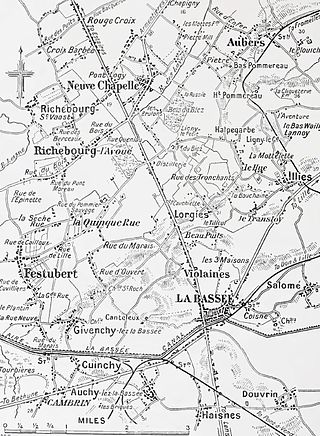

Winter operations 1914–1915 is the name given to military operations during the First World War, from 23 November 1914 – 6 February 1915, in the 1921 report of the British government Battles Nomenclature Committee. The operations took place on the part of the Western Front held by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), in French and Belgian Flanders.

The Battle of Mont Sorrel was a local operation in World War I by three divisions of the German 4th Army and three divisions of the British Second Army in the Ypres Salient, near Ypres in Belgium, from 2 to 13 June 1916.

The Battle of La Bassée was fought by German and Franco-British forces in northern France in October 1914, during reciprocal attempts by the contending armies to envelop the northern flank of their opponent, which has been called the Race to the Sea. The 6th Army took Lille before a British force could secure the town and the 4th Army attacked the exposed British flank further north at Ypres. The British were driven back and the German army occupied La Bassée and Neuve Chapelle. Around 15 October, the British recaptured Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée but failed to recover La Bassée.

The Battle of Pilckem Ridge was the opening attack of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. The British Fifth Army, supported by the Second Army on the southern flank and the French 1reArmée on the northern flank, attacked the German 4th Army, which defended the Western Front from Lille northwards to the Ypres Salient in Belgium and on to the North Sea coast. On 31 July, the Anglo-French armies captured Pilckem Ridge and areas on either side, the French attack being a great success. After several weeks of changeable weather, heavy rain fell during the afternoon of 31 July.

The Capture of La Boisselle was a tactical incident during the Battle of Albert, the name given by the British to the first two weeks of the Battle of the Somme. The village of La Boisselle forms part of the small commune of Ovillers-la-Boisselle about 22 mi (35 km) north-east of Amiens in the Somme department in Picardie in northern France. To the north-east of La Boisselle lies Ovillers; by 1916, the village was called Ovillers by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to avoid confusion with La Boisselle, south of the road.

The Gas attacks at Wulverghem were German cloud gas releases during the First World War on British troops at Wulverghem in the municipality of Heuvelland, near Ypres in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The gas attacks were part of the sporadic fighting between battles in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. The British Second Army held the ground from Messines Ridge northwards to Steenstraat and the divisions opposite the German XXIII Reserve Corps had received warnings of a gas attack. From 21 to 23 April, British artillery-fire exploded several gas cylinders in the German lines around Spanbroekmolen, which released greenish-yellow clouds. A gas alert was given on 25 April when the wind began to blow from the north-east and routine work was suspended; on 29 April, two German soldiers deserted and warned that an attack was imminent. Just after midnight on 30 April, the German attack began and over no man's land, a gas cloud drifted on the wind into the British defences, then south-west towards Bailleul.

The Loss of the Kink Salient occurred during a local attack on 11 May 1916, by the 3rd Bavarian Division on the positions of the 15th (Scottish) Division. The attack took place at the west end of the Hohenzollern Redoubt near Loos, on the Western Front during the First World War. An unprecedented bombardment demolished the British front line, then specially trained German assault units rushed the survivors and captured the British front line and the second line of defence; British tunnellers were trapped in their galleries and taken prisoner.

The 177th Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers created by the British Army during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines under enemy lines, as well as other underground work such as the construction of deep dugouts for troop accommodation, the digging of subways, saps, cable trenches and underground chambers for signals and medical services.

In World War I, the area around Hooge on Bellewaerde Ridge, about 2.5 mi (4 km) east of Ypres in Flanders in Belgium, was one of the easternmost sectors of the Ypres Salient and was the site of much fighting between German and Allied forces.

Hill 60 is a World War I battlefield memorial site and park in the Zwarteleen area of Zillebeke south of Ypres, Belgium. It is located about 4.6 kilometres (2.9 mi) from the centre of Ypres and directly on the railway line to Comines. Before the First World War the hill was known locally as Côte des Amants. The site comprises two areas of raised land separated by the railway line; the northern area was known by soldiers as Hill 60 while the southern part was known as The Caterpillar.

The Actions of St Eloi Craters from 27 March to 16 April 1916, were local operations in the Ypres Salient of Flanders, during the First World War by the German 4th Army and the British Second Army. Sint-Elooi is a village about 5 km (3.1 mi) south of Ypres in Belgium. The British dug six galleries under no man's land, placed large explosive charges under the German defences and blew them at 4:15 a.m. on 27 March. The 27th Division captured all but craters 4 and 5. The 46th Reserve Division counter-attacked but the British captured craters 4 and 5 on 30 March. The Canadian Corps took over, despite the disadvantage of relieving troops in action.

The Gheluvelt Plateau actions, July–August 1917 took place from 31 July to 27 August, during the Third Battle of Ypres in Belgium, in the First World War. The British Fifth Army and the German 4th Army fought for possession of the plateau at the highest part of the ridges to the south-east, east and north-east of Ypres in West Flanders. The 4th Army had been building defensive positions in the Ypres Salient since 1915 and the Gheluvelt Plateau was the most fortified section of the front. The Fifth Army had made the plateau its main objective during the Battle of Pilckem Ridge but the II Corps advance was contained short of its objectives and German counter-attacks later recaptured some ground.

The Capture of Westhoek took place on the Gheluvelt Plateau near Ypres in Belgium, during the Third Battle of Ypres, in the First World War. The British Fifth Army attacked the Gheluvelt Plateau at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge but the German 4th Army had fortified its positions in the Ypres Salient since the Second Battle of Ypres. The British reached the first objective in the south and the second objective on the northern flank, losing some ground to German counter-attacks. A British attack due on 2 August was postponed because torrential rain from the afternoon of 31 July until 5 August washed out the battlefield.

The Capture of Wytschaete was a tactical incident in the Battle of Messines on the Western Front during the First World War. On 7 June, the ridge was attacked by the British Second Army; the 36th (Ulster) Division and the 16th (Irish) Division of IX Corps captured the fortified village of Wytschaete on the plateau of Messines Ridge, which had been held by the German 4th Army since the First Battle of Ypres.

The Capture of Beaumont-Hamel was a tactical incident that took place during the Battle of the Somme in the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November) during the second British attempt to take the village. Beaumont-Hamel is a commune in the Somme department of Picardy in northern France. The village had been attacked on 1 July, the First Day of the Somme. The German 2nd Army defeated the attack, inflicting many British and Newfoundland Regiment casualties.