The Andalusian dialects of Spanish are spoken in Andalusia, Ceuta, Melilla, and Gibraltar. They include perhaps the most distinct of the southern variants of peninsular Spanish, differing in many respects from northern varieties, and also from Standard Spanish. Due to the large population of Andalusia, the Andalusian dialects are among the ones with more speakers in Spain. Within Spain, other southern dialects of Spanish share some core elements of Andalusian, mainly in terms of phonetics – notably Canarian Spanish, Extremaduran Spanish and Murcian Spanish as well as, to a lesser degree, Manchegan Spanish.

The Mozarabs is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians who lived under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus following the conquest of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom by the Umayyad Caliphate. Although their descendants remained unconverted to Islam, they were mostly fluent in Arabic and adopted elements of Arabic culture. The local Romance vernaculars, heavily permeated by Arabic and spoken by Christians and Muslims alike, have also come to be known as the Mozarabic language. Mozarabs were mostly Roman Catholics of the Visigothic or Mozarabic Rite.

A kharja or kharjah, is the final refrain of a muwashshah, a lyric genre of Al-Andalus written in Arabic or Ibero-Romance.

Al-Andalus was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The term is used by modern historians for the former Islamic states based in modern Spain and Portugal. At its greatest geographical extent, its territory occupied most of the peninsula and a part of present-day southern France, Septimania, and for nearly a century extended its control from Fraxinet over the Alpine passes which connect Italy to Western Europe. The name more specifically describes the different Arab or Berber states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492, though the boundaries changed constantly as the Christian Reconquista progressed, eventually shrinking to the south and finally to the vassalage of the Emirate of Granada.

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, was a continuum of related Romance dialects spoken in the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula, known as Al-Andalus. Mozarabic descends from Late Latin and early Romance dialects spoken in Hispania up to the 8th century and was spoken until around the 13th century when it either was replaced or merged with the northern peninsular Romance varieties, mostly Spanish (Castilian), Catalan and Portuguese.

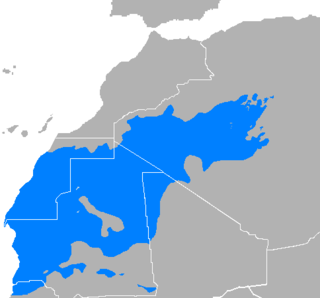

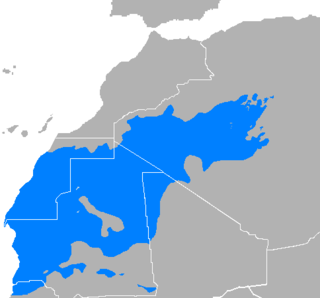

Hassānīya is a variety of Maghrebi Arabic spoken by Mauritanian Arab-Berbers and the Sahrawi. It was spoken by the Beni Ḥassān Bedouin tribes, who extended their authority over most of Mauritania and Morocco's southeastern and Western Sahara between the 15th and 17th centuries. Hassaniya Arabic was the language spoken in the pre-modern region around Chinguetti.

Maghrebi Arabic is a vernacular Arabic dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb region, in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Western Sahara, and Mauritania. It includes Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, and Hassaniya Arabic. Speakers of Maghrebi Arabic are primarily Arab-Berbers who call their language Derdja, Derja, Derija or Darija. This serves to differentiate the spoken vernacular from Standard Arabic. The Maltese language is believed to be derived from Siculo-Arabic and ultimately from Tunisian Arabic, as it contains some typical Maghrebi Arabic areal characteristics.

While many languages have numerous dialects that differ in phonology, the contemporary spoken Arabic language is more properly described as a continuum of varieties. This article deals primarily with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the standard variety shared by educated speakers throughout Arabic-speaking regions. MSA is used in writing in formal print media and orally in newscasts, speeches and formal declarations of numerous types.

Andalusian classical music or Andalusi music is a genre of music originally developed in al-Andalus by the Muslim population of Andalusia and the Moors, it then spread and influenced many different styles across the Maghreb after the Expulsion of the Moriscos. It originated in the music of Al-Andalus between the 9th and 15th centuries. Some of its poems derive from famous authors such as Al-Shushtari, Ibn al-Khatib and Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic, terms used mostly by Western linguists, is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; occasionally, it also refers to spoken Arabic that approximates this written standard. MSA is the language used in academia, print and mass media, law and legislation, though it is generally not spoken as a first language, similar to Classical Latin. It is a pluricentric standard language taught throughout the Arab world in formal education, differing significantly from many vernacular varieties of Arabic that are commonly spoken as mother tongues in the area; these are only partially mutually intelligible with both MSA and with each other depending on their proximity in the Arabic dialect continuum.

Muwashshah is the name for both an Arabic poetic form and a secular musical genre. The poetic form consists of a multi-lined strophic verse poem written in classical Arabic, usually consisting of five stanzas, alternating with a refrain with a running rhyme. It was customary to open with one or two lines which matched the second part of the poem in rhyme and meter; in North Africa poets ignore the strict rules of Arabic meter while the poets in the East follow them. The musical genre of the same name uses muwaššaḥ texts as lyrics, still in classical Arabic. This tradition can take two forms: the waṣla of Aleppo and the Andalusi nubah of the western part of the Arab world.

The Spanish language has a long history of borrowing words, expressions and subtler features of other languages it has come in contact with.

Algerian Arabic is a dialect derived from the form of Arabic spoken in northern Algeria. It belongs to the Maghrebi Arabic language continuum and is partially mutually intelligible with Tunisian and Moroccan.

Arabic influence on the Spanish language overwhelmingly dates from the Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula between 711 and 1492. The influence results mainly from the large number of Arabic loanwords and derivations in Spanish, plus a few other less obvious effects.

Zajal is a traditional form of oral strophic poetry declaimed in a colloquial dialect. While there is little evidence of the exact origins of the zajal, the earliest recorded zajal poet was the poet Ibn Quzman of al-Andalus who lived from 1078 to 1160. It is generally conceded that the early ancestors of Levantine dialectical poetry were the Andalusian zajal and muwashshaḥah, brought to Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean by Arabs fleeing Spain in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. An early master of Egyptian zajal was the fourteenth century zajjāl Abu ʿAbd Allāh al-Ghubārī. Zajal's origins may be ancient but it can be traced back to at least the 12th century. It is most alive in Lebanon today, and the Maghreb and particularly Algeria, and in the Levant, especially in Lebanon, Palestine and in Jordan where professional zajal practitioners can attain high levels of recognition and popularity. Zajal is semi-improvised and semi-sung and is often performed in the format of a debate between zajjalin. It is usually accompanied by percussive musical instruments and a chorus of men who sing parts of the verse.

The varieties of Arabic, a Semitic language within the Afroasiatic family originating in the Arabian Peninsula, are the linguistic systems that Arabic speakers speak natively. There are considerable variations from region to region, with degrees of mutual intelligibility. Many aspects of the variability attested to in these modern variants can be found in the ancient Arabic dialects in the peninsula. Likewise, many of the features that characterize the various modern variants can be attributed to the original settler dialects. Some organizations, such as Ethnologue and the International Organization for Standardization, consider these approximately 30 different varieties to be different languages, while others, such as the Library of Congress, consider them all to be dialects of Arabic.

Arab-Berbers are an ethnolinguistic group of the Maghreb, a vast region of North Africa in the western part of the Arab world along the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Arab-Berbers are people of mixed Arab and Berber origin, most of whom speak a variant of Maghrebi Arabic as their native language, although about 16 to 25 million speak various Berber languages. Many Arab-Berbers identify primarily as Arab and secondarily as Berber.

Palestinian Arabic is a dialect continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by most Palestinians in Palestine, Israel and in the Palestinian diaspora populations. Together with Jordanian Arabic, it has the ISO 639-3 language code "ajp", known as South Levantine Arabic.

Palatalization is a historical-linguistic sound change that results in a palatalized articulation of a consonant or, in certain cases, a front vowel. Palatalization involves change in the place or manner of articulation of consonants, or the fronting or raising of vowels. In some cases, palatalization involves assimilation or lenition.

The phonological system of the Hejazi Arabic consists of approximately 26 to 28 native consonant phonemes and 8 vowel phonemes:, in addition to 2 diphthongs:. Consonant length and vowel length are both distinctive in Hejazi.