Related Research Articles

The Finnish language is spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns elsewhere. Unlike the Indo-European languages spoken in neighbouring countries, such as Swedish and Norwegian, which are North Germanic languages, or Russian, which is a Slavic language, Finnish is a Uralic language of the Finnic languages group. Typologically, Finnish is agglutinative. As in some other Uralic languages, Finnish has vowel harmony, and like other Finnic languages, it has consonant gradation.

The imperative mood is a grammatical mood that forms a command or request.

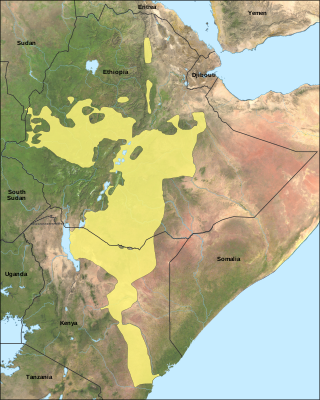

Oromo, historically also called Galla, which is regarded by the Oromo as pejorative, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

Bengali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Bengali, an Indo-European language spoken in the Indian subcontinent. Given that Bengali has two forms, Bengali: চলিত ভাষা and Bengali: সাধু ভাষা, it is important to note that the grammar discussed below applies fully only to the Bengali: চলিত (cholito) form. Shadhu bhasha is generally considered outdated and no longer used either in writing or in normal conversation. Although Bengali is typically written in the Bengali script, a romanization scheme is also used here to suggest the pronunciation.

Georgian grammar has many distinctive and extremely complex features, such as split ergativity and a polypersonal verb agreement system.

Argobba is an Ethiopian Semitic language spoken in several districts of Afar, Amhara, and Oromia regions of Ethiopia by the Argobba people. It belongs to the South Ethiopic languages subgroup, and is closely related to Amharic.

Wintu is a Wintu language which was spoken by the Wintu people of Northern California. It was the northernmost member of the Wintun family of languages. The Wintun family of languages was spoken in the Shasta County, Trinity County, Sacramento River Valley and in adjacent areas up to the Carquinez Strait of San Francisco Bay. Wintun is a branch of the hypothetical Penutian language phylum or stock of languages of western North America, more closely related to four other families of Penutian languages spoken in California: Maiduan, Miwokan, Yokuts, and Costanoan.

The morphology of the Welsh language has many characteristics likely to be unfamiliar to speakers of English or continental European languages like French or German, but has much in common with the other modern Insular Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Cornish, and Breton. Welsh is a moderately inflected language. Verbs inflect for person, number, tense, and mood, with affirmative, interrogative, and negative conjugations of some verbs. There is no case inflection in Modern Welsh.

The grammar of Classical Nahuatl is agglutinative, head-marking, and makes extensive use of compounding, noun incorporation and derivation. That is, it can add many different prefixes and suffixes to a root until very long words are formed. Very long verbal forms or nouns created by incorporation, and accumulation of prefixes are common in literary works. New words can thus be easily created.

The Ojibwe language is an Algonquian North American indigenous language spoken throughout the Great Lakes region and westward onto the northern plains. It is one of the largest indigenous language north of Mexico in terms of number of speakers, and exhibits a large number of divergent dialects. For the most part, this article describes the Minnesota variety of the Southwestern dialect. The orthography used is the Fiero Double-Vowel System.

Tübatulabal is an Uto-Aztecan language, traditionally spoken in Kern County, California, United States. It is the traditional language of the Tübatulabal, who still speak the traditional language in addition to English. The language originally had three main dialects: Bakalanchi, Pakanapul and Palegawan.

This article describes the grammar of Tigrinya, a South Semitic language which is spoken primarily in Eritrea and Ethiopia, and is written in Ge'ez script.

In Hebrew, verbs, which take the form of derived stems, are conjugated to reflect their tense and mood, as well as to agree with their subjects in gender, number, and person. Each verb has an inherent voice, though a verb in one voice typically has counterparts in other voices. This article deals mostly with Modern Hebrew, but to some extent, the information shown here applies to Biblical Hebrew as well.

Unless otherwise indicated, Tigrinya verbs in this article are given in the usual citation form, the third person singular masculine perfect.

The Nukak language is a language of uncertain classification, perhaps part of the macrofamily Puinave-Maku. It is very closely related to Kakwa.

Dirasha is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. It is spoken in the Omo region of Ethiopia, in the hills west of Lake Chamo, around the town of Gidole.

The morphology of the Welsh language shows many characteristics perhaps unfamiliar to speakers of English or continental European languages like French or German, but has much in common with the other modern Insular Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Cornish, and Breton. Welsh is a moderately inflected language. Verbs conjugate for person, tense and mood with affirmative, interrogative and negative conjugations of some verbs. A majority of prepositions inflect for person and number. There are few case inflections in Literary Welsh, being confined to certain pronouns.

This article deals with the grammar of the Udmurt language.

Old Norse has three categories of verbs and two categories of nouns. Conjugation and declension are carried out by a mix of inflection and two nonconcatenative morphological processes: umlaut, a backness-based alteration to the root vowel; and ablaut, a replacement of the root vowel, in verbs.

Arabic verbs, like the verbs in other Semitic languages, and the entire vocabulary in those languages, are based on a set of two to five consonants called a root. The root communicates the basic meaning of the verb, e.g. ك-ت-ب k-t-b 'write', ق-ر-ء q-r-ʾ 'read', ء-ك-ل ʾ-k-l 'eat'. Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as person, gender, number, tense, mood, and voice.

References

- ↑ Arbore at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ↑ Klaus Wedekind, "Sociolinguistic Survey Report of the Languages of the Gawwada, Tsamay and Diraasha Areas with Excursions to Birayle (Ongota) and Arbore (Irbore) Part II" SIL Electronic Survey Reports SILESR 2002-066. Includes a word-list of Arbore with 320 entries.

- ↑ "2007 Census". Archived from the original on 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- 1 2 Hayward 1984.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 51, the phoneme characters are altered to reflect the sound values according to the IPA.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 51.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 52.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 54.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 58.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 62–88.

- ↑ Hayward, Richard (2003). "Arbore language". Encyclopedia Aethiopica. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 166–178.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 215.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 216.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 315–318.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 271–274.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 308–313.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, p. 184–185.

- ↑ Hayward 1984, pp. 314–315.

- Hayward, Dick (1984). The Arbore Language: A First Investigation, Including a Vocabulary. Kuschitische Sprachstudien 2. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen. 1974. Kuschitistik 1972. in: Voigt, W (ed.) XIII. Deutscher Orientalistentag - Vorträge, pp. 318-328. Wiesbaden: Steiner.