The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2012, the Cushitic languages with over one million speakers were Oromo, Somali, Beja, Afar, Hadiyya, Kambaata, and Sidama.

Ongota is a moribund language of southwest Ethiopia. UNESCO reported in 2012 that out of a total ethnic population of 115, only 12 elderly native speakers remained, the rest of their small village on the west bank of the Weito River having adopted the Tsamai language instead. The default word order is subject–object–verb. The classification of the language is obscure.

Lowland East Cushitic is a group of roughly two dozen diverse languages of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. Its largest representatives are Oromo and Somali.

The Maa languages are a group of closely related Eastern Nilotic languages spoken in parts of Kenya and Tanzania by more than a million speakers. They are subdivided into North and South Maa. The Maa languages are related to the Lotuko languages spoken in South Sudan.

The Yaaku are a people who are said to have lived in regions of southern Ethiopia and central Kenya, possibly through to the 18th century. The language they spoke is today called Yaakunte. The Yaaku assimilated a hunter-gathering population, whom they called Mukogodo, when they first settled in their place of origin and the Mukogodo adopted the Yaakunte language. However, the Yaaku were later assimilated by a food producing population and they lost their way of life. The Yaakunte language was kept alive for sometime by the Mukogodo who maintained their own hunter-gathering way of life, but they were later immersed in Maasai culture and adopted the Maa language and way of life. The Yaakunte language is today facing extinction but is undergoing a revival movement. In the present time, the terms Yaaku and Mukogodo, are used to refer to a population living in Mukogodo forest west of Mount Kenya.

Yaaku is a moribund Afroasiatic language of the Cushitic branch, spoken in Kenya. Speakers are all older adults.

The Rendille are a Cushitic ethnic group inhabiting the Eastern Province of Kenya.

Kenya is a multilingual country. The two official languages of Kenya, Swahili and English, are widely spoken as lingua francas; however, including second-language speakers, Swahili is more widely spoken than English. Swahili is a Bantu language native to East Africa and English is inherited from British colonial rule.

The languages of Ethiopia include the official languages of Ethiopia, its national and regional languages, and a large number of minority languages, as well as foreign languages.

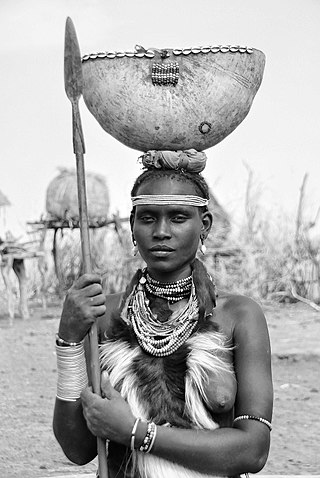

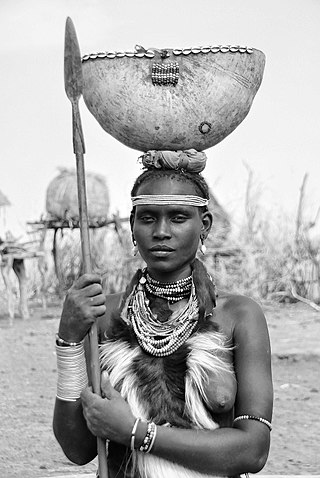

The Daasanach are an ethnic group inhabiting parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Sudan. Their main homeland is in the Debub Omo Zone of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region, adjacent to Lake Turkana. According to the 2007 national census, they number 48,067 people, of whom 1,481 are urban dwellers.

Daasanach is a Cushitic language spoken by the Daasanach in Ethiopia, South Sudan and Kenya whose homeland is along the Lower Omo River and on the shores of Lake Turkana.

The (Western) Omo–Tana or Arboroid languages belong to the Afro-Asiatic family and are spoken in Ethiopia and Kenya.

Aweer (Aweera), also known as Boni, is a Cushitic language of Eastern Kenya. The Aweer people, known by the arguably derogatory exonym Boni, are historically a hunter-gatherer people, traditionally subsisting on hunting, gathering, and collecting honey. Their ancestral lands range along the Kenyan coast from the Lamu and Ijara Districts into Southern Somalia's Badaade District.

Dizin is an Omotic language of the Afro-Asiatic language family spoken by the Dizi people, primarily in the Maji woreda of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region, located in southwestern Ethiopia. The 2007 census listed 33,927 speakers. A population of 17,583 was identified as monolinguals in 1994.

The Omo–Tana languages are a branch of the Cushitic family and are spoken in Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia and Kenya. The largest member is Somali. There is some debate as to whether the Omo–Tana languages form a single group, or whether they are individual branches of Lowland East Cushitic. Blench (2006) restricts the name to the Western Omo–Tana languages, and calls the others Macro-Somali.

The Ethiopian language area is a hypothesized linguistic area that was first proposed by Charles A. Ferguson, who posited a number of phonological and morphosyntactic features that were found widely across Ethiopia and Eritrea, including the Ethio-Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic languages but not the Nilo-Saharan languages.

The Arbore are an ethnic group living in southern Ethiopia, near Lake Chew Bahir. The Arbore people are pastoralists. With a total population of 6,850, the Abore population is divided into four villages, named: Gandareb, Kulaama, Murale, and Eegude.

The El Molo, also known as Elmolo, Dehes, Fura-Pawa and Ldes, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the northern Eastern Province of Kenya. They historically spoke the El Molo language as a mother tongue, an Afro-Asiatic language of the Cushitic branch, and now most El Molo speak Samburu.

Cushitic-speaking peoples are the ethnolinguistic groups who speak Cushitic languages natively. Today, the Cushitic languages are spoken as a mother tongue primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north and south in Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, and Tanzania.

Proto-Cushitic is the reconstructed proto-language common ancestor of the Cushitic language family. Its words and roots are not directly attested in any written works, but have been reconstructed through the comparative method, which finds regular similarities between languages not explained by coincidence or word-borrowing, and extrapolates ancient forms from these similarities.