Related Research Articles

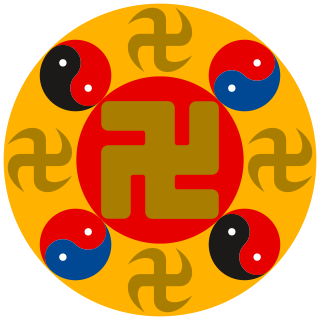

Falun Gong or Falun Dafa is a new religious movement. Falun Gong was founded by its leader Li Hongzhi in China in the early 1990s. Falun Gong has its global headquarters in Dragon Springs, a 173-hectare (427-acre) compound in Deerpark, New York, United States, near the residence of Li Hongzhi.

Human rights in China are poor, as per reviews by international bodies, such as human rights treaty bodies and the United Nations Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC), their supporters, and other proponents claim that existing policies and enforcement measures are sufficient to guard against human rights abuses. However, other countries, international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) including Human Rights in China and Amnesty International, and citizens, lawyers, and dissidents inside the country, state that the authorities in mainland China regularly sanction or organize such abuses.

Li Hongzhi is a Chinese religious leader. He is the founder and leader of Falun Gong, or Falun Dafa, a United States–based new religious movement. Li began his public teachings of Falun Gong on 13 May 1992 in Changchun, and subsequently gave lectures and taught Falun Gong exercises across China.

The 610 Office was a security agency in the People's Republic of China. Named for the date of its creation on June 10, 1999, it was established for the purpose of coordinating and implementing the persecution of Falun Gong. The 610 Office was the implementation arm of the Central Leading Group on Dealing with the Falun Gong (CLGDF), also known as the Central Leading Group on Dealing with Heretical Religions, a leading small group of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Because it was a CCP-led office with no formal legal mandate, it is sometimes described as an extralegal organisation.

Freedom of religion in China may be referring to the following entities separated by the Taiwan Strait:

Falun Gong, also called Falun Dafa, is a spiritual practice and system of beliefs that combines the practice of meditation with the moral philosophy articulated by its leader and founder, Li Hongzhi. It emerged on the public radar in the Spring of 1992 in the northeastern Chinese city of Changchun, and was classified as a system of qigong identifying with the Buddhist tradition. Li claimed to have both supernatural powers like the ability to prevent illness, as well having eternal youth and promised that others can attain supernatural powers and eternal youth by following his teachings. Falun Gong initially enjoyed official sanction and support from Chinese government agencies, and the practice grew quickly on account of the simplicity of its exercise movements, impact on health, the absence of fees or formal membership, and moral and philosophical teachings.

Falun Gong, a new religious movement that combines meditation with the moral philosophy articulated by founder Li Hongzhi, first began spreading widely in China in 1992. Li's first lectures outside mainland China took place in Paris in 1995. At the invitation of the Chinese ambassador to France, he lectured on his teachings and practice methods to the embassy staff and others. From that time on, Li gave lectures in other major cities in Europe, Asia, Oceania, and North America. He has resided permanently in the United States since 1998. Falun Gong is now practiced in some 70 countries worldwide, and the teachings have been translated to over 40 languages. The international Falun Gong community is estimated to number in the hundreds of thousands, though participation estimates are imprecise on account of a lack of formal membership.

Li Hongzhi published the Teachings of Falun Gong in Changchun, China in 1992. They cover a wide range of topics ranging from spiritual, scientific and moral to metaphysical.

The 2001 Tiananmen Square self-immolation incident took place in Tiananmen Square in central Beijing, on the eve of Chinese New Year on 23 January 2001. There is controversy over the incident; Chinese government sources say that five members of Falun Gong, a new religious movement that is banned in mainland China, set themselves on fire in the square. Falun Gong sources disputed the accuracy of these portrayals, and claimed that their teachings explicitly forbid violence or suicide. Some journalists have claimed that the self-immolations were staged.

Zhong Gong (中功) is a spiritual movement based on qigong founded in 1987 by Zhang Hongbao. The full name (中华养生益智功) translates to "China Health Care and Wisdom Enhancement Practice." The system distinguished itself from other forms of qigong by its strong emphasis on commercialisation, and a targeted strategy that aimed to build a national commercial organisation in China in the 1990s.

James Roger Lewis was an American philosophy professor at Wuhan University. He was a religious studies scholar, sociologist of religion, and writer, who specialized in the academic study of new religious movements, astrology, and New Age.

The Weiquan movement is a non-centralized group of lawyers, legal experts, and intellectuals in China who seek to protect and defend the civil rights of the citizenry through litigation and legal activism. The movement, which began in the early 2000s, has organized demonstrations, sought reform via the legal system and media, defended victims of human rights abuses, and written appeal letters, despite opposition from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Among the issues adopted by Weiquan lawyers are property and housing rights, protection for AIDS victims, environmental damage, religious freedom, freedom of speech and the press, and defending the rights of other lawyers facing disbarment or imprisonment.

The persecution of Falun Gong is the campaign initiated in 1999 by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to eliminate the spiritual practice of Falun Gong in China, maintaining a doctrine of state atheism. It is characterized by a multifaceted propaganda campaign, a program of enforced ideological conversion and re-education and reportedly a variety of extralegal coercive measures such as arbitrary arrests, forced labor and physical torture, sometimes resulting in death.

Falun Gong is a spiritual practice taught by Li Hongzhi. Practicing Falun Gong or protesting on its behalf is forbidden in Mainland China, yet the practice remains legal in Hong Kong, which has greater protections of civil and political liberties under “One country, Two systems.” Since 1999 practitioners in Hong Kong have staged demonstrations and protests against the Chinese government, and assisted those fleeing persecution in China. Nonetheless, Falun Gong practitioners have encountered some restrictions in Hong Kong as a result of political pressure from Beijing. The treatment of Falun Gong by Hong Kong authorities has often been used as a bellwether to gauge the integrity of the one country two systems model.

Protesters and dissidents in the People's Republic of China (PRC) espouse a wide variety of grievances, most commonly in the areas of unpaid wages, compensation for land development, local environmental activism, or NIMBY activism. Tens of thousands of protests occur each year. National level protests are less common. Notable protests include the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, the April 1999 demonstration by Falun Gong practitioners at Zhongnanhai, the 2008 Tibetan unrest, the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, and the 2022 COVID-19 protests.

Allegations of forced organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners and other political prisoners in China have raised concern within the international community. According to a report by former lawmaker David Kilgour, human rights lawyer David Matas, and journalist Ethan Gutmann of the US government-affiliated Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, political prisoners, mainly Falun Gong practitioners, are being executed "on-demand" in order to provide organs for transplant to recipients. Reports have shown that organ harvesting has been used to advance the Chinese Communist Party's persecution of Falun Gong and because of the financial incentives available to the institutions and individuals involved in the trade. A report by The Washington Post has disputed some of the allegations, saying that China does not import sufficient quantities of immunosuppressant drugs, used by transplant recipients, to carry out such quantities of organ harvesting. However, a report by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation stated that a group of experts alleged the Post's article made an “elementary statistical error” and omitted unofficial pharmacy data in Chinese hospitals.

Antireligious campaigns in China are a series of policies and practices taken as part of the Chinese Communist Party's official promotion of state atheism, coupled with its persecution of people with spiritual or religious beliefs, in the People's Republic of China. Antireligious campaigns were launched in 1949, after the Chinese Communist Revolution, and they continue to be waged against Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and members of other religious communities in China.

Heterodox teaching is a concept in the law of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and its administration regarding new religious movements and their suppression. Also translated as 'cults' or 'evil religions', "heterodox teachings" are defined in Chinese law as organizations and religious movements that either fraudulently use religion to carry out other illegal activities, deify their leaders, spread "superstition" to confuse or deceive the public, or "disturb the social order" by harming people's lives or property.

Falun Gong and the Future of China is a 2008 book by David Ownby, published by Oxford University Press. The book is about the Chinese new religious movement Falun Gong, and covers its history and the group's media and portrayals of itself. The book received generally positive reviews.

Transnational repression by China refers to efforts by the government of the People's Republic of China to exert control and silence dissent beyond its national borders. Transnational repression targets groups and individuals perceived as threats to or critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The methods include digital surveillance, physical intimidation, coercion, and misuse of international legal systems.

References

- 1 2 Thornton, Patricia M. (2003). "The New Cybersects: Resistance and Repression in the Reform era.". In Perry, Elizabeth; Selden, Mark (eds.). Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance (second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 149–50.

- ↑ Thornton, Patricia M. (2008). "Manufacturing Dissent in Transnational China: Boomerang, Backfire or Spectacle?". In O’Brien, Kevin J. (ed.). Popular Contention in China. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Dunn, Emily C. (2007). "Netizens of heaven: contesting orthodoxies on the Chinese Protestant web". Asian Studies Review. 31 (4): 447–58. doi:10.1080/10357820701710740.

- ↑ Karaflogka, Anastasia (2002). "Religious Discourse and Cyberspace". Religion. 32 (4): 279–291. doi:10.1006/reli.2002.0405. Karaflogka cites the cyber-diocese of Partenia and Falun Gong as two examples of cyberreligions.

- ↑ Costanza-Chock, Sasha (2003). "Mapping the Repertoire of Electronic Contention". In Opel, Andrew; Pompper, Donnalyn (eds.). Representing Resistance: Media, Civil Disobedience and the Global Justice Movement. Greenwood. pp. 173–191.

- ↑ "Cyber-sectarianism". The Layalina Review on Public Diplomacy and Arab Media. IV (22): 5–6. 10–23 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008.

- ↑ Maghaireh, Alaedin (July–December 2008). "Shariah Law and Cyber-Sectarian Conflict: How can Islamic Criminal Law respond to cyber crime?" (PDF). International Journal of Cyber Criminology. 2 (2): 338.

- ↑ Gladney, Dru C. (2004). "Chapter 11: Cyber-separatism". Dislocating China: Reflections on Muslims, Minorities and Other Subaltern Subjects. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 229-259.

- ↑ Blackadder, Des (8 April 2008). "Your Views: Panorama in Ballymena". Ballymena Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020.

- ↑ Moore, Dermod (10 March 2006). "Bootboy: Gougers, langers and victimology". Dublin theatre reviews… and other passions. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007.

- ↑ On the use of the term to describe the migration of political and religious sectarian divisions to cyberspace, see also Biege, Bernd (5 November 2007). "Bernd's Ireland Travel Blog: Fáilte Second Ireland". Archived from the original on 20 January 2011.

- ↑ See "What's In A Name. Rose By Any Other Name Still Belongs In A Fist". New America: the blog of the Social Democrats USA, standing in the legacy of the Socialist Party of America . 17 June 2008.

- ↑ aka Bootboy (14 March 2006). "I predict a riot". Hot Press.

- ↑ Virilio, Paul (2005). The Information Bomb. Verso. p. 41.

- ↑ Hauck, Rita M. (Summer 2009). Stratospheric Transparency: Perspectives on Internet Privacy (PDF). Forum on Public Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2013.