Mining is the extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agricultural processes, or feasibly created artificially in a laboratory or factory. Ores recovered by mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, limestone, chalk, dimension stone, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. The ore must be a rock or mineral that contains valuable constituent, can be extracted or mined and sold for profit. Mining in a wider sense includes extraction of any non-renewable resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the early modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire, the economy was in tatters and many of the towns abandoned. After several centuries of Germanic immigration, new identities and cultures began to emerge, developing into kingdoms that competed for power. A rich artistic culture flourished under the Anglo-Saxons, producing epic poems such as Beowulf and sophisticated metalwork. The Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity in the 7th century, and a network of monasteries and convents were built across England. In the 8th and 9th centuries, England faced fierce Viking attacks, and the fighting lasted for many decades. Eventually, Wessex was established as the most powerful kingdom and promoted the growth of an English identity. Despite repeated crises of succession and a Danish seizure of power at the start of the 11th century, it can also be argued that by the 1060s England was a powerful, centralised state with a strong military and successful economy.

The Great Famine of 1315–1317 was the first of a series of large-scale crises that struck parts of Europe early in the 14th century. Most of Europe was affected. The famine caused many deaths over an extended number of years and marked a clear end to the period of growth and prosperity from the 11th to the 13th centuries.

The study of the economies of the ancient city-state of Rome and its empire during the Republican and Imperial periods remains highly speculative. There are no surviving records of business and government accounts, such as detailed reports of tax revenues, and few literary sources regarding economic activity. Instead, the study of this ancient economy is today mainly based on the surviving archeological and literary evidence that allow researchers to form conjectures based on comparisons with other more recent pre-industrial economies.

Mining in Cornwall and Devon, in the southwest of Britain, is thought to have begun in the early-middle Bronze Age with the exploitation of cassiterite. Tin, and later copper, were the most commonly extracted metals. Some tin mining continued long after the mining of other metals had become unprofitable, but ended in the late 20th century. In 2021, it was announced that a new mine was extracting battery-grade lithium carbonate, more than 20 years after the closure of the last South Crofty tin mine in Cornwall in 1998.

Mining was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain. Britain was rich in resources such as copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire. Sufficient supply of metals was needed to fulfil the demand for coinage and luxury artefacts by the elite. The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle Ages.

Mark David Bailey, is a British academic, headteacher and former rugby union player. Since 2020, he has been Professor of Later Medieval History at the University of East Anglia. In 2019, he delivered the James Ford Lectures in British History at Oxford University, which were later published as a book, After the Black Death: Economy, society, and the law in fourteenth-century England.

Liquation is a metallurgical method for separating metals from an ore or alloy. The material must be heated until one of the metals starts to melt and drain away from the other and can be collected. This method was largely used to remove lead containing silver from copper, but it can also be used to remove antimony from ore minerals, and refine tin.

In the history of England, the High Middle Ages spanned the period from the Norman Conquest in 1066 to the death of King John, considered by some historians to be the last Angevin king of England, in 1216. A disputed succession and victory at the Battle of Hastings led to the conquest of England by William of Normandy in 1066. This linked the Kingdom of England with Norman possessions in the Kingdom of France and brought a new aristocracy to the country that dominated landholding, government and the church. They brought with them the French language and maintained their rule through a system of castles and the introduction of a feudal system of landholding. By the time of William's death in 1087, England formed the largest part of an Anglo-Norman empire, ruled by nobles with landholdings across England, Normandy and Wales. William's sons disputed succession to his lands, with William II emerging as ruler of England and much of Normandy. On his death in 1100 his younger brother claimed the throne as Henry I and defeated his brother Robert to reunite England and Normandy. Henry was a ruthless yet effective king, but after the death of his only male heir William Adelin, he persuaded his barons to recognise his daughter Matilda as heir. When Henry died in 1135 her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself proclaimed king, leading to a civil war known as The Anarchy. Eventually Stephen recognised Matilda's son Henry as his heir and when Stephen died in 1154, he succeeded as Henry II.

The history of England during the Late Middle Ages covers from the thirteenth century, the end of the Angevins, and the accession of Henry II – considered by many to mark the start of the Plantagenet dynasty – until the accession to the throne of the Tudor dynasty in 1485, which is often taken as the most convenient marker for the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the English Renaissance and early modern Britain.

A bal maiden, from the Cornish language bal, a mine, and the English "maiden", a young or unmarried woman, was a female manual labourer working in the mining industries of Cornwall and western Devon, at the south-western extremity of Great Britain. The term has been in use since at least the early 18th century. At least 55,000 women and girls worked as bal maidens, and the actual number is likely to have been much higher.

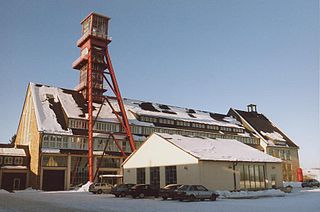

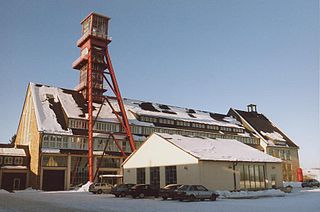

During the Middle Ages, between the 5th and 16th century AD, Western Europe saw a period of growth in the mining industry. The first important mines were those at Goslar in the Harz mountains, taken into commission in the 10th century. Another notable mining town is Falun in Sweden where copper has been mined since at least the 10th century and possibly even earlier.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

This article covers the Economic history of Europe from about 1000 AD to the present. For the context, see History of Europe.

The medieval English saw their economy as comprising three groups – the clergy, who prayed; the knights, who fought; and the peasants, who worked the land and towns involved in international trade. Over the five centuries of the Middle Ages, the English economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban and extraction economies, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns and mines developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England had a weak government, by later standards, overseeing an economy dominated by rented farms controlled by gentry, and a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

The economics of English agriculture in the Middle Ages is the economic history of English agriculture from the Norman invasion in 1066, to the death of Henry VII in 1509. England's economy was fundamentally agricultural throughout the period, though even before the invasion the market economy was important to producers. Norman institutions, including serfdom, were superimposed on an existing system of open fields.

The economics of English towns and trade in the Middle Ages is the economic history of English towns and trade from the Norman invasion in 1066, to the death of Henry VII in 1509. Although England's economy was fundamentally agricultural throughout the period, even before the invasion the market economy was important to producers. Norman institutions, including serfdom, were superimposed on a mature network of well-established towns involved in international trade. Over the next five centuries the English economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban areas, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England would have a weak early modern government overseeing an economy involving a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

The Ore Mountain Mining Region is an industrial heritage landscape, over 800 years old, in the border region of the Ore Mountains between the German state of Saxony and North Bohemia in the Czech Republic. It is characterised by a plethora of historic, largely original, monuments to technology, as well as numerous individual monuments and collections related to the historic mining industry of the region. On 6 July 2019, the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, because of its exceptional testimony to the advancement of mining technology over the past 800 years.

The Great Slump was an economic depression that occurred in England from the 1430s to the 1480s.

The Great Bullion Famine was a shortage of precious metals that struck Europe in the 15th century, with the worst years of the famine lasting from 1457 to 1464. During the Middle Ages, gold and silver coins saw widespread use as currency in Europe, and facilitated trade with the Middle East and Asia; the shortage of these metals therefore became a problem for European economies. The main cause for the bullion famine was outflow of silver to the East unequaled by European mining output, although 15th century contemporaries believed the bullion famine to be caused by hoarding.