The Araneomorphae are an infraorder of spiders. They are distinguishable by chelicerae (fangs) that point diagonally forward and cross in a pinching action, in contrast to the Mygalomorphae, where they point straight down. Araneomorphs comprise the vast majority of living spiders.

Crevice weaver spiders (Filistatidae) comprise cribellate spiders with features that have been regarded as "primitive" for araneomorph spiders. They are weavers of funnel or tube webs. The family contains 18 genera and more than 120 described species worldwide.

Spider taxonomy is the part of taxonomy that is concerned with the science of naming, defining and classifying all spiders, members of the Araneae order of the arthropod class Arachnida, which has more than 48,500 described species. However, there are likely many species that have escaped the human eye as well as specimens stored in collections waiting to be described and classified. It is estimated that only one-third to one half of the total number of existing species have been described.

Cribellum literally means "little sieve", and in biology the term generally applies to anatomical structures in the form of tiny perforated plates.

The Palpimanoidea or palpimanoids, also known as assassin spiders, are a group of araneomorph spiders, originally treated as a superfamily. As with many such groups, its circumscription has varied. As of September 2018, the following five families were included:

The Leptonetoidea are a superfamily of haplogyne araneomorph spiders with three families. Phylogenetic studies have provided weak support for the relationship among the families. The placement of one of the families within the Haplogynae has been questioned.

The Dysderoidea are a clade or superfamily of araneomorph spiders. The monophyly of the group, initially consisting of the four families Dysderidae, Oonopidae, Orsolobidae and Segestriidae, has consistently been recovered in phylogenetic studies. In 2014, a new family, Trogloraptoridae, was created for a recently discovered species Trogloraptor marchingtoni. It was suggested that Trogloraptoridae may be the most basal member of the Dysderoidea clade. However, a later study found that Trogloraptoridae was placed outside the Dysderoidea and concluded that it was not part of this clade.

The Eresoidea or eresoids are a group of araneomorph spiders that have been treated as a superfamily. As usually circumscribed, the group contains three families: Eresidae, Hersiliidae and Oecobiidae. Studies and reviews based on morphology suggested the monophyly of the group; more recent gene-based studies have found the Eresidae and Oecobiidae to fall into different clades, placing doubt on the acceptability of the taxon. Some researchers have grouped Hersiliidae and Oecobiidae into the separate superfamily Oecobioidea, a conclusion supported in a 2017 study, which does not support Eresoidea.

The Agelenoidea or agelenoids are a superfamily or informal group of entelegyne araneomorph spiders. Phylogenetic studies since 2000 have not consistently recovered such a group, with more recent studies rejecting it.

The Austrochiloidea or austrochiloids are a group of araneomorph spiders, treated as a superfamily. The taxon contains two families of eight-eyed spiders:

The Haplogynae or haplogynes are one of the two main groups into which araneomorph spiders have traditionally been divided, the other being the Entelegynae. Morphological phylogenetic studies suggested that the Haplogynae formed a clade; more recent molecular phylogenetic studies refute this, although many of the ecribellate haplogynes do appear to form a clade, Synspermiata.

The anatomy of spiders includes many characteristics shared with other arachnids. These characteristics include bodies divided into two tagmata, eight jointed legs, no wings or antennae, the presence of chelicerae and pedipalps, simple eyes, and an exoskeleton, which is periodically shed.

This glossary describes the terms used in formal descriptions of spiders; where applicable these terms are used in describing other arachnids.

The two palpal bulbs – also known as palpal organs and genital bulbs – are the copulatory organs of a male spider. They are borne on the last segment of the pedipalps, giving the spider an appearance often described as like wearing boxing gloves. The palpal bulb does not actually produce sperm, being used only to transfer it to the female. Palpal bulbs are only fully developed in adult male spiders and are not completely visible until after the final moult. In the majority of species of spider, the bulbs have complex shapes and are important in identification.

Orbiculariae is a potential clade of araneomorph spiders, uniting two groups that make orb webs. Phylogenetic analyses based on morphological characters have generally recovered this clade; analyses based on DNA have regularly concluded that the group is not monophyletic. The issue relates to the origin of orb webs: whether they evolved early in the evolutionary history of entelegyne spiders, with many groups subsequently losing the ability to make orb webs, or whether they evolved later, with fewer groups having lost this ability. As of September 2018, the weight of the evidence strongly favours the non-monophyly of "Orbiculariae" and hence the early evolution of orb webs, followed by multiple changes and losses.

Synspermiata is a clade of araneomorph spiders, comprising most of the former "haplogynes". They are united by having simpler genitalia than other araneomorph spiders, lacking a cribellum, and sharing an evolutionary history of synspermia – a particular way in which spermatozoa are grouped together when transferred to the female.

Nephilidae is a spider family commonly referred to as golden orb-weavers. The various genera in the Nephilidae family were formerly placed in Tetragnathidae and Araneidae. All nephilid genera partially renew their webs.

Leucauge mariana is a long-jawed orb weaver spider, native to Central America and South America. Its web building and sexual behavior have been studied extensively. Males perform several kinds of courtship behavior to induce females to copulate and to use their sperm.

Larinia jeskovi is a species of the family of orb weaver spiders and a part of the genus Larinia. It is distributed throughout the Americas, Africa, Australia, Europe, and Asia and commonly found in wet climes such as marshes, bogs, and rainforests. Larinia jeskovi have yellow bodies with stripes and range from 5.13 to 8.70 millimeters in body length. They build their webs on plants with a small height above small bodies of waters or wetlands. After sunset and before sunrise are the typical times they hunt and build their web. Males usually occupy a female's web instead of making their own. The mating behavior is noteworthy as male spiders often mutilate external female genitalia to reduce sperm competition while female spiders resort to sexual cannibalism to counter such mechanisms. The males also follow an elaborate courtship ritual to attract the female. The bite of Larinia jeskovi is not known to be of harm to humans.

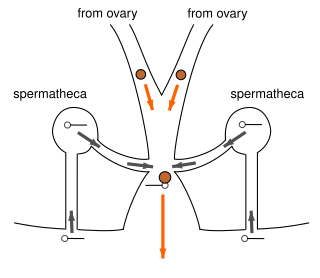

Sahastata wesolowskae is a species of crevice weaver in the genus Sahastata that lives in Oman. It was first described in 2020 by Ivan Magalhaes, Mark Stockmann, Yuri Marusik and Sergei Zonstein. The spider is small, with a carapace that is between 1.67 and 3.36 mm long and an abdomen that is between 3.73 and 4.94 mm long. The female is larger than the male, darker in color and has a more rounded abdomen. Both have a V-shaped pattern towards the middle of the carapace, but it is clearer on the female. The male has a long and slightly bent embolus. The female has an endogyne with distinctive spermathecae. It is these copulatory organs that most clearly differentiate the species from other spiders in the genus.