The leg is the entire lower limb of the human body, including the foot, thigh or sometimes even the hip or buttock region. The major bones of the leg are the femur, tibia, and adjacent fibula. The thigh is between the hip and knee, while the calf (rear) and shin (front) are between the knee and foot.

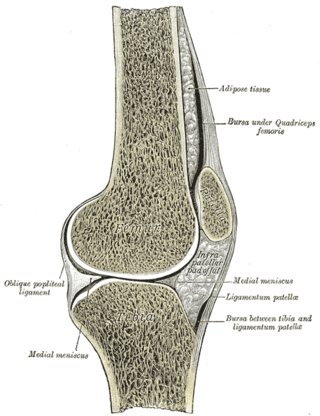

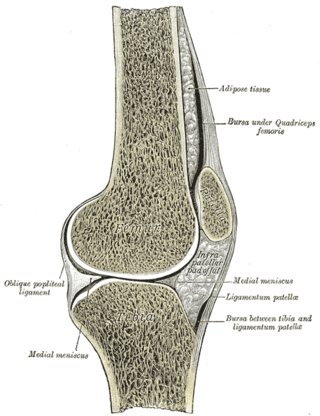

In humans and other primates, the knee joins the thigh with the leg and consists of two joints: one between the femur and tibia, and one between the femur and patella. It is the largest joint in the human body. The knee is a modified hinge joint, which permits flexion and extension as well as slight internal and external rotation. The knee is vulnerable to injury and to the development of osteoarthritis.

In human anatomy, a hamstring is any one of the three posterior thigh muscles between the hip and the knee.

The tibia, also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates ; it connects the knee with the ankle. The tibia is found on the medial side of the leg next to the fibula and closer to the median plane. The tibia is connected to the fibula by the interosseous membrane of leg, forming a type of fibrous joint called a syndesmosis with very little movement. The tibia is named for the flute tibia. It is the second largest bone in the human body, after the femur. The leg bones are the strongest long bones as they support the rest of the body.

The patella, also known as the kneecap, is a flat, rounded triangular bone which articulates with the femur and covers and protects the anterior articular surface of the knee joint. The patella is found in many tetrapods, such as mice, cats, birds and dogs, but not in whales, or most reptiles.

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is small, placed toward the back of the head of the tibia, below the knee joint and excluded from the formation of this joint. Its lower extremity inclines a little forward, so as to be on a plane anterior to that of the upper end; it projects below the tibia and forms the lateral part of the ankle joint.

The popliteal artery is a deeply placed continuation of the femoral artery opening in the distal portion of the adductor magnus muscle. It courses through the popliteal fossa and ends at the lower border of the popliteus muscle, where it branches into the anterior and posterior tibial arteries.

The biceps femoris is a muscle of the thigh located to the posterior, or back. As its name implies, it consists of two heads; the long head is considered part of the hamstring muscle group, while the short head is sometimes excluded from this characterization, as it only causes knee flexion and is activated by a separate nerve.

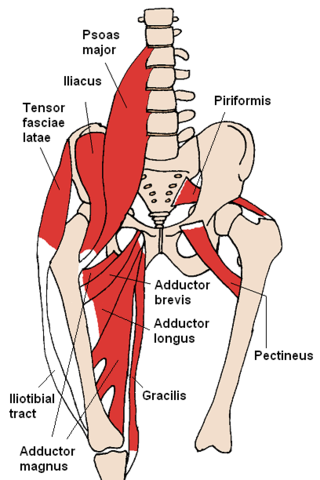

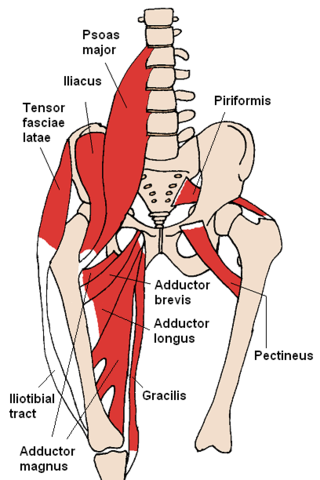

The adductor magnus is a large triangular muscle, situated on the medial side of the thigh.

The semimembranosus muscle is the most medial of the three hamstring muscles in the thigh. It is so named because it has a flat tendon of origin. It lies posteromedially in the thigh, deep to the semitendinosus muscle. It extends the hip joint and flexes the knee joint.

The semitendinosus is a long superficial muscle in the back of the thigh. It is so named because it has a very long tendon of insertion. It lies posteromedially in the thigh, superficial to the semimembranosus.

The popliteus muscle in the leg is used for unlocking the knees when walking, by laterally rotating the femur on the tibia during the closed chain portion of the gait cycle. In open chain movements, the popliteus muscle medially rotates the tibia on the femur. It is also used when sitting down and standing up. It is the only muscle in the posterior (back) compartment of the lower leg that acts just on the knee and not on the ankle. The gastrocnemius muscle acts on both joints.

The medial meniscus is a fibrocartilage semicircular band that spans the knee joint medially, located between the medial condyle of the femur and the medial condyle of the tibia. It is also referred to as the internal semilunar fibrocartilage. The medial meniscus has more of a crescent shape while the lateral meniscus is more circular. The anterior aspects of both menisci are connected by the transverse ligament. It is a common site of injury, especially if the knee is twisted.

The lateral meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous band that spans the lateral side of the interior of the knee joint. It is one of two menisci of the knee, the other being the medial meniscus. It is nearly circular and covers a larger portion of the articular surface than the medial. It can occasionally be injured or torn by twisting the knee or applying direct force, as seen in contact sports.

The knee examination, in medicine and physiotherapy, is performed as part of a physical examination, or when a patient presents with knee pain or a history that suggests a pathology of the knee joint.

The posterior compartment of the thigh is one of the fascial compartments that contains the knee flexors and hip extensors known as the hamstring muscles, as well as vascular and nervous elements, particularly the sciatic nerve.

The knee bursae are the fluid-filled sacs and synovial pockets that surround and sometimes communicate with the knee joint cavity. The bursae are thin-walled, and filled with synovial fluid. They represent the weak point of the joint, but also provide enlargements to the joint space. They can be grouped into either communicating and non-communicating bursae or, after their location – frontal, lateral, or medial.

The arcuate popliteal ligament is an Y-shaped extracapsular ligament of the knee. It is formed as a thickening of the posterior fibres of the joint capsule of the knee. It reinforces the knee joint capsule inferolaterally.

Posterolateral corner injuries of the knee are injuries to a complex area formed by the interaction of multiple structures. Injuries to the posterolateral corner can be debilitating to the person and require recognition and treatment to avoid long term consequences. Injuries to the PLC often occur in combination with other ligamentous injuries to the knee; most commonly the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). As with any injury, an understanding of the anatomy and functional interactions of the posterolateral corner is important to diagnosing and treating the injury.

Medial knee injuries are the most common type of knee injury. The medial ligament complex of the knee consists of: