Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry, mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine infantry.

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects.

Trench warfare is the type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. Trench warfare became archetypically associated with World War I (1914–1918), when the Race to the Sea rapidly expanded trench use on the Western Front starting in September 1914.

Urban warfare is combat conducted in urban areas such as towns and cities. Urban combat differs from combat in the open at both the operational and the tactical levels. Complicating factors in urban warfare include the presence of civilians and the complexity of the urban terrain. Urban combat operations may be conducted to capitalize on strategic or tactical advantages associated with the possession or the control of a particular urban area or to deny these advantages to the enemy.

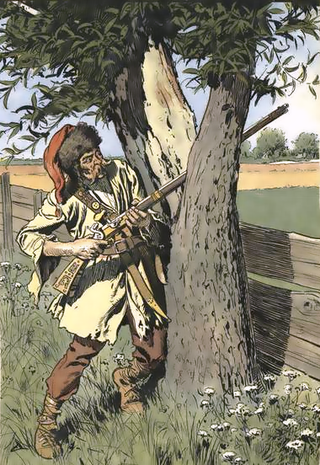

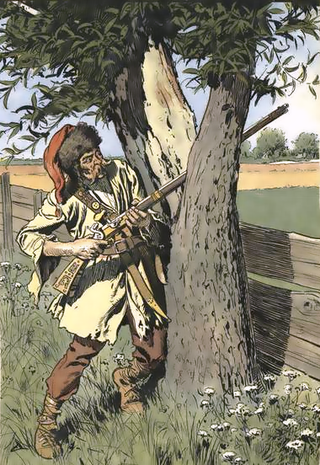

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an irregular open formation that is much more spread out in depth and in breadth than a traditional line formation. Their purpose is to harass the enemy by engaging them in only light or sporadic combat to delay their movement, disrupt their attack, or weaken their morale. Such tactics are collectively called skirmishing.

AirLand Battle was the overall conceptual framework that formed the basis of the US Army's European warfighting doctrine from 1982 into the late 1990s. AirLand Battle emphasized close coordination between land forces acting as an aggressively maneuvering defense, and air forces attacking rear-echelon forces feeding those front line enemy forces. AirLand Battle replaced 1976's "Active Defense" doctrine, and was itself replaced by "Full Spectrum Operations" in 2001.

Lanchester's laws are mathematical formulae for calculating the relative strengths of military forces. The Lanchester equations are differential equations describing the time dependence of two armies' strengths A and B as a function of time, with the function depending only on A and B.

Maneuver warfare, or manoeuvre warfare, is a military strategy which seeks to shatter the enemy's overall cohesion and will to fight.

Armoured warfare or armored warfare, is the use of armored fighting vehicles in modern warfare. It is a major component of modern methods of war. The premise of armoured warfare rests on the ability of troops to penetrate conventional defensive lines through use of manoeuvre by armoured units.

Defeat in detail, or divide and conquer, is a military tactic of bringing a large portion of one's own force to bear on small enemy units in sequence, rather than engaging the bulk of the enemy force all at once. This exposes one's own units to many small risks but allows for the eventual destruction of an entire enemy force.

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A pitched battle is not a chance encounter such as a meeting engagement, or where one side is forced to fight at a time not of its choosing such as happens in a siege or an ambush. Pitched battles are usually carefully planned, to maximize one's strengths against an opponent's weaknesses, and use a full range of deceptions, feints, and other manoeuvres. They are also planned to take advantage of terrain favourable to one's force. Forces strong in cavalry for example will not select swamp, forest, or mountain terrain for the planned struggle. For example, Carthaginian general Hannibal selected relatively flat ground near the village of Cannae for his great confrontation with the Romans, not the rocky terrain of the high Apennines. Likewise, Zulu commander Shaka avoided forested areas or swamps, in favour of rolling grassland, where the encircling horns of the Zulu Impi could manoeuvre to effect. Pitched battles continued to evolve throughout history as armies implemented new technology and tactics.

Operation Veritable was the northern part of an Allied pincer movement that took place between 8 February and 11 March 1945 during the final stages of the Second World War. The operation was conducted by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group, primarily consisting of the First Canadian Army under Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar and the British XXX Corps under Lieutenant-general Brian Horrocks.

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver is a movement of an armed force around an enemy force's side, or flank, to achieve an advantageous position over it. Flanking is useful because a force's fighting strength is typically concentrated in its front, therefore, to circumvent an opposing force's front and attack its flank is to concentrate one's own offense in the area where the enemy is least able to concentrate defense.

The Prandtl lifting-line theory is a mathematical model in aerodynamics that predicts lift distribution over a three-dimensional wing based on its geometry. It is also known as the Lanchester–Prandtl wing theory.

The Battle of Hannut was a Second World War battle fought during the Battle of Belgium which took place between 12 and 14 May 1940 at Hannut in Belgium. It was the largest tank battle in the campaign. It was also the largest clash of tanks in armoured warfare history at the time.

Diffusion is the net movement of anything generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical potential. It is possible to diffuse "uphill" from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration, like in spinodal decomposition. Diffusion is a stochastic process due to the inherent randomness of the diffusing entity and can be used to model many real-life stochastic scenarios. Therefore, diffusion and the corresponding mathematical models has applications in several fields, beyond physics, such as statistics, probability theory, information theory, neural networks, finance and marketing etc.

The primary application of wind turbines is to generate energy using the wind. Hence, the aerodynamics is a very important aspect of wind turbines. Like most machines, wind turbines come in many different types, all of them based on different energy extraction concepts.

Roman infantry tactics refers to the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The focus below is primarily on Roman tactics: the "how" of their approach to battle, and how it stacked up against a variety of opponents over time. It does not attempt detailed coverage of things like army structure or equipment. Various battles are summarized to illustrate Roman methods with links to detailed articles on individual encounters.

Combat effectiveness is the capacity or performance of a military force to succeed in undertaking an operation, mission or objective. Determining optimal combat effectiveness is crucial in the armed forces, whether they are deployed on land, air or sea. Combat effectiveness is an aspect of military effectiveness and can be attributed to the strength of combat support including the quality and quantity of logistics, weapons and equipment as well as military tactics, the psychological states of soldiers, level of influence of leaders, skill and motivation that can arise from nationalism to survival are all capable of contributing to success on the battlefield.