Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Lawrence of Austria, Duke of Teschen was an Austrian field-marshal, the third son of Emperor Leopold II and his wife, Maria Luisa of Spain. He was also the younger brother of Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor. He was epileptic, but achieved respect both as a commander and as a reformer of the Austrian army. He was considered one of Napoleon's most formidable opponents and one of the greatest generals of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Carl Philipp Gottfriedvon Clausewitz was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral" and political aspects of waging war. His most notable work, Vom Kriege, though unfinished at his death, is considered a seminal treatise on military strategy and science.

Martin Levi van Creveld is an Israeli military historian and theorist.

Sir John Desmond Patrick Keegan was an English military historian, lecturer, author and journalist. He wrote many published works on the nature of combat between prehistory and the 21st century, covering land, air, maritime, intelligence warfare and the psychology of battle.

Antoine-Henri Jomini was a Swiss military officer who served as a general in French and later in Russian service, and one of the most celebrated writers on the Napoleonic art of war. Jomini was largely self-taught in military strategy, and his ideas are a staple at military academies, the United States Military Academy at West Point being a prominent example; his theories were thought to have affected many officers who later served in the American Civil War. He may have coined the term logistics in his Summary of the Art of War (1838).

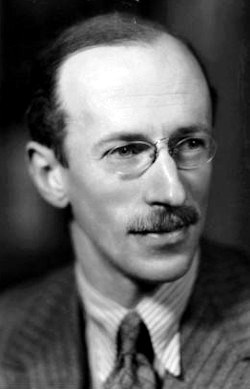

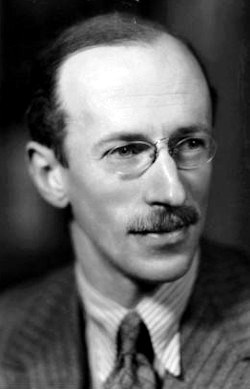

Hans Rothfels was a German historian. He supported an idea of authoritarian German state, dominance of Germany over Europe and was hostile to Germany's eastern neighbours. After his applications for honorary Aryan status were rejected, due to his Jewish ancestry and increased persecution of Jewish people by Nazis, he was forced to emigrate to the United Kingdom and later to the United States during the Second World War, after which he became opposed to the Nazi regime. Rothfels returned to West Germany after 1945 where he continued to influence history teaching and became an influential figure among West German scholars.

Annihilation is a military strategy in which an attacking army seeks to entirely destroy the military capacity of the opposing army. This strategy can be executed in a single planned pivotal battle, called a "battle of annihilation". A successful battle of annihilation is accomplished through the use of tactical surprise, application of overwhelming force at a key point, or other tactics performed immediately before or during the battle.

The concept of absolute war was a theoretical construct developed by the Prussian military theorist General Carl von Clausewitz in his famous but unfinished philosophical exploration of war, Vom Kriege. It is discussed only in the first half of Book VIII and it does not appear in sections of the text written later.

Military theory is the study of the theories which define, inform, guide and explain war and warfare. Military Theory analyses both normative behavioral phenomena and explanatory causal aspects to better understand war and how it is fought. It examines war and trends in warfare beyond simply describing events in military history. While military theories may employ the scientific method, theory differs from Military Science. Theory aims to explain the causes for military victory and produce guidance on how war should be waged and won, rather than developing universal, immutable laws which can bound the physical act of warfare or codifying empirical data, such as weapon effects, platform operating ranges, consumption rates and target information, to aid military planning.

Henry Spenser Wilkinson was the first Chichele Professor of Military History at Oxford University. While he was an English writer known primarily for his work on military subjects, he had wide interests. Earlier in his career he was the drama critic for London's Morning Post.

Otto Jolle Matthijs Jolles (1911–1968) performed a major service to strategic studies in the United States by providing the first American translation of Carl von Clausewitz's magnum opus, On War. Jolles himself is a bit obscure to students of military affairs, largely because his translation of On War was his only published effort in that field. Even his nationality has been misidentified—he has been variously identified as Hungarian, Czech, and Dutch. Military historian Jay Luvaas once quoted an unidentified Israeli professor as saying "whereas the first English translation was by an Englishman who did not know German, the 1943 American translation was by a Hungarian who did not know English." There is little in the Jolles translation to warrant such a comment. In the field of German literature, Jolles is quite well known, especially for his work on Friedrich Schiller. Most of his published work, however, is in German.

Christopher Bassford is an American military historian, best known for his works on the Prussian military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz.

Klemens Wilhelm Jacob Meckel was a general in the Prussian army and foreign advisor to the government of Meiji period Japan.

Michael Friedrich Benedikt Baron von Melas was a Transylvanian-born field marshal of Greek descent for the Austrian Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

Azar Gat is an Israeli researcher of war, nationalism and ideology, and a professor at the School of Political Science, Government, and International Relations at Tel Aviv University. His research combines expertise in the fields of history, evolution, anthropology, and social sciences. He is the author of twelve books that deal with the history of military thought, the fundamental questions of war and its causes, the struggles between democratic and non-democratic states, nationalism, and the phenomenon of ideological fixation. His books have been translated into many languages.

Jean Colin was a French general and military writer. He has been judged "one of the brilliant members of the French General Staff before 1914."

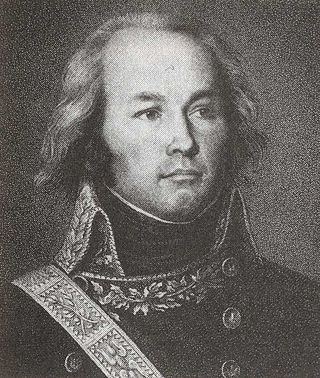

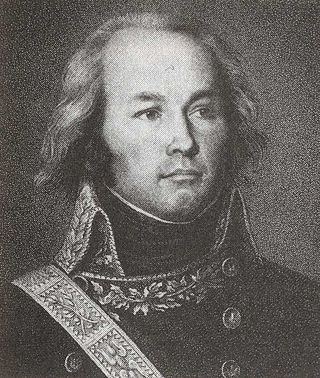

Claude Jacques Lecourbe was a French general during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, was a British soldier, military historian, and military theorist. He wrote a series of military histories that proved influential among strategists. Arguing that frontal assault was bound to fail at great cost in lives, as proven in World War I, he recommended the "indirect approach" and reliance on fast-moving armoured formations.

Peter Karl Ott von Bátorkéz was a military officer in the armies of the Habsburg monarchy. Of Hungarian origin, Ott fought in the wars against the Kingdom of Prussia, Ottoman Turkey, and the First French Republic in the last half of the 18th century. During the French Revolutionary Wars, he rose in rank to general officer and twice campaigned against the army of Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy. He played a key role in the Marengo campaign in 1800. He was Proprietor (Inhaber) of an Austrian Hussar regiment from 1801 to 1809.

Mozg Armii, in English The Brain of the Army, is a three-volume military theory book published between 1927 and 1929. It is the most important work of Boris Shaposhnikov, a Soviet military commander then in command of the Moscow military region. Mozg Armii gained a wide popularity throughout the Red Army, and Shaposhnikov himself was held in high regard by Joseph Stalin.