Related Research Articles

Siderite is a mineral composed of iron(II) carbonate (FeCO3). Its name comes from the Ancient Greek word σίδηρος (sídēros), meaning "iron". A valuable iron ore, it consists of 48% iron and lacks sulfur and phosphorus. Zinc, magnesium, and manganese commonly substitute for the iron, resulting in the siderite-smithsonite, siderite-magnesite, and siderite-rhodochrosite solid solution series.

A polystrate fossil is a fossil of a single organism that extends through more than one geological stratum. The word polystrate is not a standard geological term. This term is typically found in creationist publications.

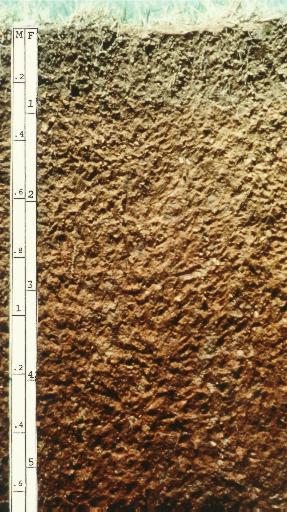

Alfisols are a soil order in USDA soil taxonomy. Alfisols form in semi-arid to humid areas, typically under a hardwood forest cover. They have a clay-enriched subsoil and relatively high native fertility. "Alf" refers to aluminium (Al) and iron (Fe). Because of their productivity and abundance, Alfisols represent one of the more important soil orders for food and fiber production. They are widely used both in agriculture and forestry, and are generally easier to keep fertile than other humid-climate soils, though those in Australia and Africa are still very deficient in nitrogen and available phosphorus. Those in monsoonal tropical regions, however, have a tendency to acidify when heavily cultivated, especially when nitrogenous fertilizers are used.

In the geosciences, paleosol is an ancient soil that formed in the past. The precise definition of the term in geology and paleontology is slightly different from its use in soil science.

The Sydney Basin is an interim Australian bioregion and is both a structural entity and a depositional area, now preserved on the east coast of New South Wales, Australia and with some of its eastern side now subsided beneath the Tasman Sea. The basin is named for the city of Sydney, on which it is centred.

The paleopedological record is, essentially, the fossil record of soils. The paleopedological record consists chiefly of paleosols buried by flood sediments, or preserved at geological unconformities, especially plateau escarpments or sides of river valleys. Other fossil soils occur in areas where volcanic activity has covered the ancient soils.

The geology of India is diverse. Different regions of India contain rocks belonging to different geologic periods, dating as far back as the Eoarchean Era. Some of the rocks are very deformed and altered. Other deposits include recently deposited alluvium that has yet to undergo diagenesis. Mineral deposits of great variety are found in the Indian subcontinent in huge quantities. Even India's fossil record is impressive in which stromatolites, invertebrates, vertebrates and plant fossils are included. India's geographical land area can be classified into the Deccan Traps, Gondwana and Vindhyan.

Paleopedology is the discipline that studies soils of past geological eras, from quite recent (Quaternary) to the earliest periods of the Earth's history. Paleopedology can be seen either as a branch of soil science (pedology) or of paleontology, since the methods it uses are in many ways a well-defined combination of the two disciplines.

Seatearth is a British coal mining term that is used in the geological literature. As noted by Jackson, a seatearth is the layer of sedimentary rock underlying a coal seam. Seatearths have also been called seat earth, "seat rock", or "seat stone" in the geologic literature. Depending on its physical characteristics, a number of different names, such as underclay, fireclay, flint clay, and ganister, can be applied to a specific seatearth.

An overbank is an alluvial geological deposit consisting of sediment that has been deposited on the floodplain of a river or stream by flood waters that have broken through or overtopped the banks. The sediment is carried in suspension, and because it is carried outside of the main channel, away from faster flow, the sediment is typically fine-grained. An overbank deposit usually consists primarily of fine sand, silt and clay. Overbank deposits can be beneficial because they refresh valley soils.

Silcrete is an indurated soil duricrust formed when surface soil, sand, and gravel are cemented by dissolved silica. The formation of silcrete is similar to that of calcrete, formed by calcium carbonate, and ferricrete, formed by iron oxide. It is a hard and resistant material, and though different in origin and nature, appears similar to quartzite. As a duricrust, there is potential for preservation of root structures as trace fossils.

The Ischigualasto Formation is a Late Triassic geological formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin of southwestern La Rioja Province and northeastern San Juan Province in northwestern Argentina. The formation dates to the late Carnian and early Norian stages of the Late Triassic, according to radiometric dating of ash beds.

Aztec Mountain is a small pyramidal mountain over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) high, just southwest of Maya Mountain and west of Beacon Valley in Victoria Land. It was so named by the New Zealand Geological Survey Antarctic Expedition (1958–59) because its shape resembles the pyramidal ceremonial platforms used by the Aztec and Maya civilizations.

The Beacon Supergroup is a geological formation exposed in Antarctica and deposited from the Devonian to the Triassic. The unit was originally described as either a formation or sandstone, and upgraded to group and supergroup as time passed. It contains a sandy member known as the Beacon Heights Orthoquartzite.

Clay Cutans are a geologic fabric that develop around ancient cavities within paleosols.

Rhizoliths are organosedimentary structures formed in soils or fossil soils (paleosols) by plant roots. They include root moulds, casts, and tubules, root petrifactions, and rhizocretions. Rhizoliths, and other distinctive modifications of carbonate soil texture by plant roots, are important for identifying paleosols in the post-Silurian geologic record. Rock units whose structure and fabric were established largely by the activity of plant roots are called rhizolites.

Gregory John Retallack is an Australian paleontologist, geologist, and author who specializes in the study of fossil soils (paleopedology). His research has examined the fossil record of soils though major events in Earth history, extending back some 4.6 billion years. Among his publications he has written two standard paleopedology textbooks, said N. Jones in Nature Geoscience "Retallack has literally written the book on ancient soils."

The Archer City Formation is a geological formation in north-central Texas, preserving fossils from the Asselian and early Sakmarian stages of the Permian period. It is the earliest component of the Texas red beds, introducing an tropical ecosystem which will persist in the area through the rest of the Early Permian. The Archer City Formation is preceded by the cool Carboniferous swamp sediments of the Markley Formation, and succeeded by the equally fossiliferous red beds of the Nocona Formation. The Archer City Formation was not named as a unique geological unit until the late 1980s. Older studies generally labelled its outcrops as the Moran or Putnam formations, which are age-equivalent marine units to the southwest.

Astropedology is the study of very ancient paleosols and meteorites relevant to the origin of life and different planetary soil systems. It is a branch of soil science (pedology) concerned with soils of the distant geologic past and of other planetary bodies to understand our place in the universe. A geologic definition of soil is “a material at the surface of a planetary body modified in place by physical, chemical or biological processes”. Soils are sometimes defined by biological activity but can also be defined as planetary surfaces altered in place by biologic, chemical, or physical processes. By this definition, the question for Martian soils and paleosols becomes, were they alive? Astropedology symposia are a new focus for scientific meetings on soil science. Advancements in understanding the chemical and physical mechanisms of pedogenesis on other planetary bodies in part led the Soil Science Society of America (SSSA) in 2017 to update the definition of soil to: "The layer(s) of generally loose mineral and/or organic material that are affected by physical, chemical, and/or biological processes at or near the planetary surface and usually hold liquids, gases, and biota and support plants". Despite our meager understanding of extraterrestrial soils, their diversity may raise the question of how we might classify them, or formally compare them with our Earth-based soils. One option is to simply use our present soil classification schemes, in which case many extraterrestrial soils would be Entisols in the United States Soil Taxonomy (ST) or Regosols in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB). However, applying an Earth-based system to such dissimilar settings is debatable. Another option is to distinguish the (largely) biotic Earth from the abiotic Solar System, and include all non-Earth soils in a new Order or Reference Group, which might be tentatively called Astrosols.

References

- ↑ "Gannister definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- 1 2 Jackson, J. A., 1997, Glossary of geology, 4th ed. American Geological Institute, Alexandria. ISBN 0-922152-34-9

- 1 2 3 Retallack, G. J., 1977. Triassic palaeosols in the upper Narrabeen Group of New South Wales. Part II: Classification and reconstruction Journal of the Geological Society of Australia . V. 24, no. 1, p. 19-35.

- 1 2 Gibling, M. R., and Rust, B.P., 1992, Silica-cemented paleosols (ganisters) in the Pennsylvanian Waddens Cove Formation, Nova Scotia, Canada in K.H. Wolf and G.V. Chilingarian, George, eds., Diagenesis, III. Developments in Sedimentology 47:621-655 ISBN 0-444-88516-1

- 1 2 Retallack, G. J., 2001, Soils of the Past, 2nd ed. New York, Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-05376-3

- ↑ Percival, C. J., 1982, Paleosols containing an albic horizon: examples from the upper Carboniferous of northern Britain in V.P. Wright, ed., pp. 87-111, Paleosols: Their Recognition and Interpretation. Princeton, Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-08405-X

- ↑ Percival, C. J., 1983, The Firestone Sill Ganister, Namurian, northern England—the A2 horizon of a podzol or podzolic palaeosol, Sedimentary Geology . V. 36, no.1, p. 41-49.

- ↑ McCarthy, T. S. and Ellery, W. N., 1995, Sedimentation on the distal reaches of the Okavango Fan, Botswana, and its bearing on calcrete and silcrete (ganister) formation, Journal of Sedimentary Research. V. A65, no.1, p. 77-90

- ↑ Jones, M.H. (2011). The Brendon Hills Iron Mines and the West Somerset Mineral Railway. Lightmoor Press. pp. 16, 148–149, 280. ISBN 9781899889-5-3-2.

- ↑ Brandt, D.J.O. (1953). The Manufacture of Iron and Steel. English Universities Press. pp. 100–104.